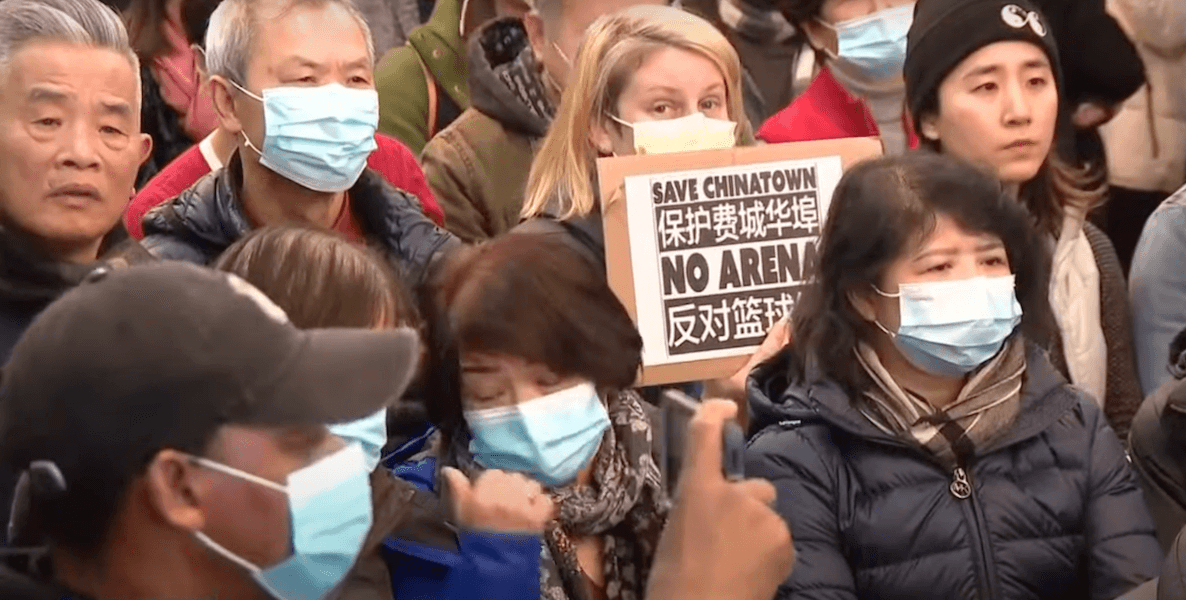

I’m betting you have a life, and wouldn’t spend two and a half hours of it tuning into the recent community meeting between Chinatown residents and a Sixers representative. But I don’t, so I did. Ostensibly, the purpose of the meeting had been for the team to present its plan for a Market Street arena to nearby residents and businesses, to get their feedback, presumably with an eye toward trying to enlist the community as a partner in the project.

No biggie, right? This is Madisonian democracy in action: A proposal is made, smart questions are asked, respectful debate ensues, and the political machinery is catalyzed to either move, or not.

Well, that’s not quite what I saw. Instead, I witnessed a disconcerting display of irrationality and incivility. It was chaos. Poor David Gould, the Sixers chief diversity and impact officer, was shouted down time and again, unable to finish a thought.

At one point, his Blackness was called into question by an angry Black audience member. “You’re gaslighting us!” someone else shouted. “Fuck you!” another audience member chimed in. Questions weren’t driven by open-minded curiosity, so much as assumptions about Gould’s (ill) intentions. Mostly, what I remember was the palpable anger on the faces of audience members.

I bring all this up not to weigh in on the relative worth of the Sixer’ arena proposal (I penned this when it was first proposed), but rather to argue that any idea that could transform an economically-challenged area of a struggling city deserves an honest airing.

“For me,” one progressive activist told author Anand Ghiridiradas, “calling in is a callout done with love. You’re actually holding people accountable. But you’re doing so through the lens of love.”

And we don’t have a helluva lot of honest airings going on lately. The Sixers arena is not an isolated case. Time and again, it seems, the hard work of public persuasion is eschewed for the easy path of name-calling and shouting-down. Used to be, if you didn’t like a public proposal, you mobilized and tried to persuade those who were undecided on the topic to your point of view. What has happened to the art of activism?

Since when does meanness work?

Jane Jacobs never told Robert Moses, through clenched teeth that portended violence, to kiss her ass; instead, she won a debate over urban planning with the legendary power broker by writing and saying things that were smarter than what he was saying and doing. She painted an alternative vision to his car and expressway-filled dream for New York and the everyday citizen sided with her.

In the 60s, World War II veterans like my dad were persuaded by the pithy protestations of Muhammad Ali — “I ain’t got no quarrel with them Viet Cong” — and the comic radicalism of Abbie Hoffman and the Yippies, who once rained cash down onto Wall Street’s Stock Exchange trading floor, brilliantly making a point about greed as the traders below elbowed each other out of the way to scoop up as many bills as possible.

And do we even need to invoke MLK’s moral suasion? Talk about an activist who changed the public will.

Just when did meanness and calling other people names persuade those who are persuadable to your point of view? Yet it seems to be the game plan du jour. Never mind that the UC Townhomes isn’t even on Penn’s campus; undeterred, rabid protestors, including students and faculty, shouted down Penn’s president and kept her from addressing incoming students. Protests that stop traffic don’t generally convince those on the fence about your issue to join your cause.

“Turning the establishment into the enemy, it’s a little easy, isn’t it? I get one eyebrow up when people want systemic change but don’t want to bother to turn up for the town-hall meeting,” said Bono (of all people).

In fact, many of the same protestors that are so fact-challenged when it comes to UC Townhomes are also on the frontlines of the anti-arena movement. Likewise, it should come as no surprise that there they are again, leading the charge against Hilco Redevelopment Partners’ Bellwether District, a 1,300-acre property borne of the ashes of the old PES Refinery in Southwest Philly.

It’s projected to provide in excess of 20,000 jobs over 15 years — providing a pathway to the middle class. When you look at a map, it’s as if they’re building a city within a city. Wouldn’t you want to at least start from the assumption that there might be a win/win to be had there? Instead, fear of anything new — even on the hollowed-out site of past environmental disaster — rules the day.

And it’s not just in Philly. In Bucks and Montgomery counties, activists — including some who don’t actually live where they’re protesting — yelled loud enough about “losing control to hedge funds and corporations” that plans to sell off water or sewer systems were tabled, despite billions in taxpayer windfall and calls for ongoing rate regulation. It’s public policymaking not by persuasion, but bullying.

Get-sh*t-done vs. performative activism

This tension between get-shit-done and performative activism is captured in author Anand Ghiridharadas’ newest book, The Persuaders: At The Front Lines of the Fight for Hearts, Minds, and Democracy. In addition to providing a surprising and heartwarming portrait of AOC’s practical ways — at one point, she even lectures Bernie Sanders to be less of a scold, playing on resentment, and more of a happy warrior — Giridharadas introduces us to the progressive activists who are moving from “calling out” to “calling in” mode.

“For me,” says one, “calling in is a callout done with love. You’re actually holding people accountable. But you’re doing so through the lens of love.”

It boils down to the merits of talk over action — which, in a democracy, by definition entails cooperation and compromise. Ghiridharadas quotes The New Yorker’s Jelani Cobb on this vexing balancing act when it comes to Black Lives Matter: While the group’s “insistent outsider status has allowed it to shape the dialogue surrounding race and criminal justice in this country, it has also sparked a debate about the limits of protest, particularly of online activism.”

I bring all this up not to weigh in on the relative worth of the Sixers’ arena proposal (I penned this when it was first proposed), but rather to argue that any idea that could transform an economically-challenged area of a struggling city deserves an honest airing.

Here in Philly, we’re seeing those limits firsthand. The takeaway from all our local case studies? If you start from a place where you’re convinced that everyone’s conspiring against you, you may make a lot of noise, but you’re not actually going to get very far. Turns out, protest is easy; problem-solving is hard.

Of all people, Bono described well learning that lesson to the New York Times Magazine in October:

Turning the establishment into the enemy, it’s a little easy, isn’t it? I get one eyebrow up when people want systemic change but don’t want to bother to turn up for the town-hall meeting …

There’s a funny moment when you realize that as an activist: The off-ramp out of extreme poverty is, ugh, commerce, it’s entrepreneurial capitalism. I spend a lot of time in countries all over Africa, and they’re like, Eh, we wouldn’t mind a little more globalization actually … It’s very easy to become patronizing. Capitalism is a wild beast. We need to tame it. But globalization has brought more people out of poverty than any other -ism. If somebody comes to me with a better idea, I’ll sign up. I didn’t grow up to like the idea that we’ve made heroes out of businesspeople, but if you’re bringing jobs to a community and treating people well, then you are a hero.

How did we get to a place where even Bono is complaining about the stultifying state of activism today? No doubt, there are many reasons. Trump (and, to a lesser degree, Sanders) unleashed a grievance-driven anger in the body politic that still courses through its veins; rather than opt for pragmatism, many on the left have mimicked Trump’s worst characteristics. Social media has allowed outrage to spread far faster than understanding. And traditional news sources, rather than slowing down and providing context and thoughtfulness, have taken the bait and shed more heat than light.

What happened to the “battlefield of ideas?”

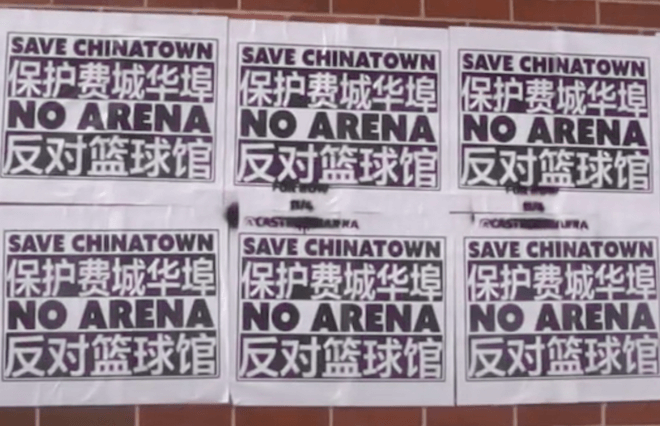

How else to explain what appears to be an Inquirer campaign against the Sixers arena? I’m agnostic on the issue, but would like to see the debate smartly engaged. Instead, there have been a steady stream of cheerleading stories about Chinatown organizing against the arena, like the news story actually headlined: A How-To Guide For Fighting Big Development: For decades, Chinatown has created a blueprint for fighting big development, with the Sixers’ proposed arena as their latest target. Here’s how they do it.

What’s happened at the Inquirer on this story is a case study in how the journalistic concept of “balance” has been distorted. The first few stories were done by business writer Joe DiStefano. Now comes the paper’s “Communities and Engagement Desk,” producing news stories that seem designed to not only convey, but champion, one community’s point of view — as if there really is one monolithic take. (Proof of an agenda is everywhere, but maybe no more so in the juxtaposition of the Chinatown “How-To” story against a headline that outs developer David Adelman — a former Citizen board member — as a billionaire with 5,000 bottles of wine and a $7,000 bottle of Tequila.)

“I promise you that Rights to Ricky Sanchez listeners are not descending upon Chinatown in 2031 to torment the locals and force English upon them,” wrote sportswriter Kevin Kinkead.

To be clear: I’m fine with the paper taking a position, even in news stories. But cop to it, and then dig in; eschew the easy stenography, arbitrate between competing sets of facts, and explain the real issues. Treat the proposal of a Center City arena as a citywide story that affects the entire region, bang away at it, and let the chips fall.

Stories like the arena, UC Townhomes, Bellwether, and even stewardship of public assets like water systems are what cities are all about — they convey the push and pull of who gets to derive value when the economic pie is ever-shrinking, yes, but they’re also a way to consider what actually goes into growing that pie.

It’s just too damn easy to buy into the name-calling and false, overly-simplistic narratives: Plutocrat: bad; chanting, placard-holding protestor: good. These issues are complex, and require smart sifting through the spin of competing self-interests. The most reasonable thing I read about the arena was, of all places, on the sports website Crossing Broad, in a story by Kevin Kinkead:

The new arena is being built on the edge of Chinatown, right on the border but not in the neighborhood, and of course it will have an impact on the area, just like any new development within a block or two of anything in Philadelphia. But some of the stuff you read is a little over the top, like a basketball arena is not going to ‘wipe out’ Chinatown …

In another story, there’s a woman talking about Chinatown being one of the few places where you can speak ‘native language without fear of being bullied or misunderstood,’ but I promise you that Rights to Ricky Sanchez listeners are not descending upon Chinatown in 2031 to torment the locals and force English upon them. Not to make light of legit concerns, but some of these complaints just aren’t rooted in reality …

If you want to talk about property values going up, resulting in increased rents and stressing the businesses on 10th/Arch/Cuthbert, then that’s an example of a real conversation to have. Bottom line, something has to replace the mess of a Fashion District, where a group of teens attacked some guy on Saturday and broke his jaw. That part of Market Street is lagging far behind and we should all be in agreement that it needs some attention.

Amen, sportswriter. Way to lay out the real issues at stake. Media has to find a way to get beyond the incendiary soundbite, and activists need to freely make their case in the court of public opinion, instead of just shouting down those with whom they disagree. They need to heed the advice of one Barack Obama, who, in 2016 at Howard University, anticipated the very depths to which our public discourse has now sunk.

“There will be times when you shouldn’t compromise your core values, your integrity, and you will have the responsibility to speak up in the face of injustice,” Obama told the students. “But listen. Engage. If the other side has a point, learn from them. If they’re wrong, rebut them. Teach them. Beat them on the battlefield of ideas.”

The battlefield of ideas. It’s been a while since we’ve engaged there, huh?

![]() RELATED COVERAGE OF COMMUNITY AND ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT

RELATED COVERAGE OF COMMUNITY AND ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT