“Are you in mourning?”

That was the text from a friend after Lori Lightfoot’s resounding defeat after only one term as mayor of Chicago. For the six of you who pay attention to these things, I’ve sung Lightfoot’s praises often in recent years as a much-needed agent of change. She was a reformer, I’d argued, someone who eschewed rigid ideology and was willing to take on a sclerotic and often corrupt city government. On day one of her administration, for example, she signed an executive order effectively declaring war on her city’s version of councilmanic prerogative.

But that’s the thing about reformers — they more often than not morph into martyrs. (See: Gorbachev, Mikhail). And in Lightfoot’s case, she may have been a co-conspirator in her own downfall, which we’ll get to.

Now that we’re 10 weeks out from our own election, there are some object lessons for Philadelphia’s candidates blowing in from Chicagoland.

Why is no one filling the Paul Vallas/Eric Adams lane?

Our public opinion polls, just like those in Chicago and the ones over a year ago in New York, show that, far and away, public safety is the number one issue on voters’ minds. And yet no candidate here has struck an emotional chord with voters and differentiated themselves as the “law and order” candidate in the way that Vallas and Adams so successfully did in those respective cities.

There’s a playbook, folks, and our candidates seem too afraid of left-wing Twitter backlash to crack it open. But Vallas and Adams prove that doing so is not pandering — and nor does it require doing a Frank Rizzo impression.

Here in Philly, we know firsthand that Vallas has many flaws as a CEO — great at vision, but not so proficient at management. But on the stump in Chicago, he talked endlessly about hiring 1,600 new cops, firing the commissioner, charging and prosecuting misdemeanors, and focusing intensely on those that law enforcement already know to be the shooters or are at extreme risk of being shot. He talked about the carrot-and-stick approach of proactive policing — commonly called focused deterrence — but here, there is precious little talk of the stick part of that equation.

For example, with the exception of a passing reference from Allan Domb, hardly anyone in the recent WHYY gun violence forum even mentioned focussed deterrence, the one strategy we know works to cut the murder rate in the short term, as nationally recognized expert David Muhammad explains in our recent podcast, How To Really Run a City, with former Mayors Kasim Reed of Atlanta and Michael Nutter of Philadelphia.

“When you’re doing the job at its best, people look you in the eye, and whatever happened, people feel like that guy feels as close to how I feel without it happening to him,” Reed says.

New evidence shows the strategy has been working here under the name Gun Violence Intervention (GVI) — though why it’s still essentially a pilot program instead of the way we now do policing department-wide is beyond me. (Philadelphia is in love with pilot programs that have already been proven to work elsewhere). Domb mentioned the strategy, but didn’t explain what it is; at this week’s Center City Business Association forum, Maria Quiñones Sánchez impressively went into depth on it.

But, still, no one has talked about crime fighting in the emotionally visceral way Kasim Reed did during his term as Atlanta mayor. He spoke directly to those waging war on at-risk communities. “They know I don’t play,” he said, referring to criminals. In our podcast, Reed and Nutter both talk about fighting crime in a way that connects to the central nervous system of a citizenry.

“If somebody breaks into your house and takes your TV out of your house, your house doesn’t feel the same,” Reed said. “And you’re enraged and you have all of these feelings … I used to say, if somebody breaks into your house and steals your TV, I want your TV back. I don’t want the damn insurance company to replace it. I want the TV. Because that’s a different energy and it really ties into how that person feels. When you’re doing the job at its best, people look you in the eye, and whatever happened, people feel like that guy feels as close to how I feel without it happening to him.”

That’s how you talk about combating crime, in stark contrast to the by-rote answers we’re hearing in the forums, whereby the only monotonic difference we can discern is that Rebecca Rhynhart has a six-point and Domb a 10-point plan.

Because guess who embraces the type of empathetic, yet tough rhetoric Reed and Nutter governed by? Black residents in war zone communities who don’t feel safe walking two blocks to get to the damned grocery store, that’s who.

Rhynhart knows all about this issue; as Controller, she wrote reports detailing the efficacy of the type of strategies espoused by Muhammad. Yet, she speaks in euphemism, referencing again and again “evidence-based strategies.” You know anyone who pulls the lever for “evidence-based strategies?” People vote for a candidate who tells those who would break the social contract that she don’t play, and who explains to would-be activists that proactive policing that offers opportunities to known bad actors while holding them accountable actually reduces the footprint of policing.

Why is everyone so scared?

Why are so few candidates connecting with the voter emotionally on this most emotional of issues? Yes, it has to do with fear of a misguided progressive backlash that sees no daylight between combating disorder and Rizzo-like police criminality. To buy into that zero-sum thinking, you’d have to think that someone like Cherelle Parker, who wants to hire 300 officers, is Bull Connor.

But it’s also attributable to widespread candidate timidity. At the ‘HYY gun violence forum, the moderators asked numerous questions — too many, in fact — that required just a show of hands. You could see just about every one of the candidates hedging their bets, tentatively raising a hand while furtively checking to see if the others were following suit. Moreover, time and again in the forums I’ve watched, this cycle’s candidates refer to one another as “my colleague.” But they’re not colleagues. They’re competitors, and this should be an argument over the future direction of the city.

A year and a half ago, the political consultant Ken Smukler came up with a “Roadmap” for local Dems to win Council seats. The Citizen got hold of it, and it’s telling to look back at his analysis now, as his number crunching of the ’21 DA’s race actually shows that there’s a lane for a Vallas or Adams-like mayoral candidate.

“I have never met anybody who has managed to piss off every single person they come in contact with — police, fire, teachers, aldermen, businesses, manufacturing,” said Alderman Susan Sadlowski Garza, who supported Lightfoot four years ago.

“This election pitted the poster-boy of progressive politics, incumbent DA Larry Krasner, against the FOP-endorsed career prosecutor, Carlos Vega,” Smukler writes. “Money did not dictate the outcome in this race. Yet Vega still garnered over 33 percent of the vote citywide. A third of the Democrat electorate, when given the choice between an Inquirer-backed, self-described progressive incumbent candidate and a conservative, FOP-backed Hispanic-surnamed career prosecutor, chose the conservative.”

Smukler dove into the numbers. Of the 64,370 votes Vega received, 33 percent came from 10 of the city’s 66 wards. In these wards, Vega received over 60 percent of the vote. In another 16 wards, Vega took between 30 and 59 percent of the vote. Keep in mind that Vega was a wholly uninspiring candidate, and yet he outperformed expectations, especially within the Greater and Lower Northeast, the River Wards, South Philly, Roxborough, Manayunk, Mount Airy, and the majority-Hispanic parts of North Philly, which had surprisingly moved towards Trump in 2016.

Let’s keep in mind that, in 2007, Michael Nutter won the primary (and, thus, effectively the mayoralty) in a five-way race with 36 percent of the vote. Today, with seven credible candidates and no clear frontrunner, the conventional wisdom is that the winner might ultimately need all of 25 to 30 percent. Well, Vega’s 33 percent in a much lower turnout election than an open mayoral primary could easily expand into the high 30s, more than enough to coronate the next mayor if a candidate emerges from the scrum who makes the voter feel safe and who convinces the electorate he or she will put the citizens’ government back to work for them: Picking up trash, filling potholes, focusing on inclusive growth and providing opportunity rather than issuing screeds about redistributing wealth.

The point is, there could be the making of a reasonable center in Philadelphia politics, if only the candidates would stop fighting over the same progressive slices of the pie. Think of it this way: Joe Biden won Philly with 600,000 votes in 2020. Jim Kenney won it with 200,000 five years prior.

It stands to reason that most of those missing 400,000 would pull the lever for someone who doesn’t just talk bloodless policy, but turns every question into a referendum on the City’s lack of public safety and says to the purveyors of mayhem: Not In My City. Not a Rizzo-era warrior, mind you; a guardian of the peace who nonetheless makes it known he or she won’t tolerate crap like the recent brazen attack of a 33-year-old woman at 15th and Chestnut or this week’s ransacking of a store by a group of teens at 10th and Chestnut. Disorder is viral; the first candidate to present him or herself as the veritable new sheriff in town will rise above the pack.

The perils of a political neophyte

Whether the polls show it or not, and whether you agree with his policies or not, what Joe Biden accomplished with a 50-50 Senate in his first two years was astounding, and a testament to the power of political dealmaking. Lightfoot, on the other hand, was a political neophyte — and it ultimately showed.

An in-depth post-mortem on The Daily Kos detailed Lightfoot’s rookie mistakes. While I cheered on her shots across the bow at the establishment, she didn’t balance that change-agent rhetoric with the hard work of managing political relationships. “I have never met anybody who has managed to piss off every single person they come in contact with — police, fire, teachers, aldermen, businesses, manufacturing,” said Alderman Susan Sadlowski Garza, who supported Lightfoot four years ago. Her colleague, Derrick Curtis, was also a Lightfoot ally — until he accidentally shot himself while cleaning his gun…and the mayor never called him.

Politics is about standing for principle, yes, but it’s also about welcoming strange bedfellows, about living to fight another day, about putting your ego aside for the greater good. When Lightfoot reportedly told the City Councilors who voted against her budget “Don’t come to me for shit” she may have thought she was playing hardball, but she was actually foreshadowing her ultimate defeat.

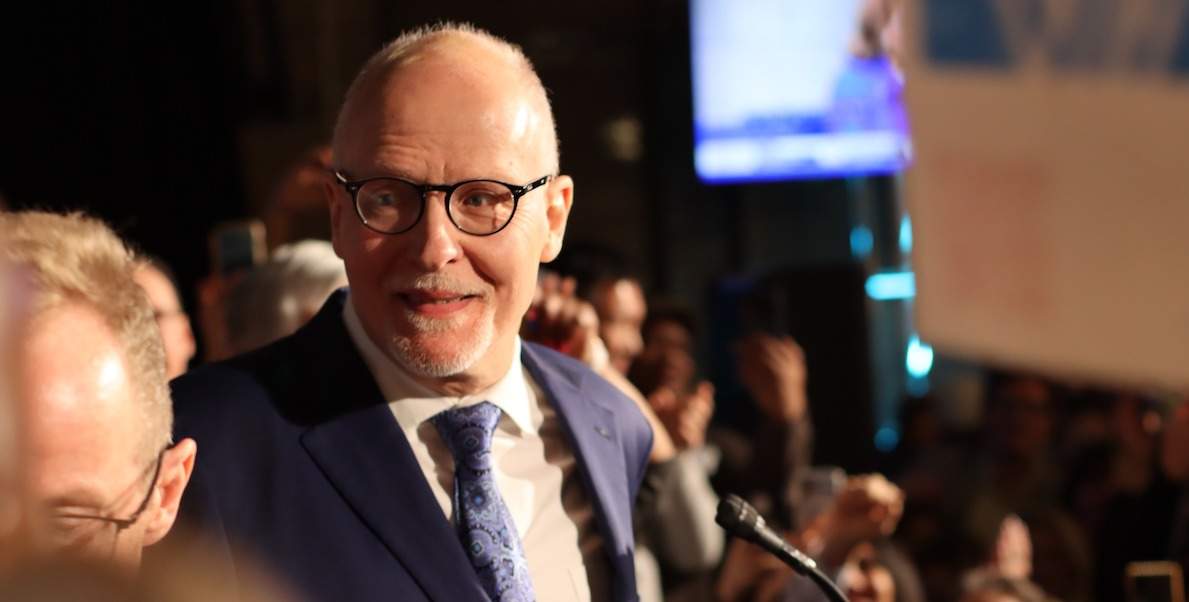

The object lesson here is most applicable to Jeff Brown, a non-politician who has suggested on the stump and in his ads that Council is incompetent. He’s not necessarily wrong, of course. It’s just that his rhetoric — much like Lightfoot’s — calls into question just how he’ll be able to work with such a historically oversensitive body. Remember, it was Mayor Ed Rendell who, in Buzz Bissinger’s brilliant book A Prayer For The City, rather colorfully observed that “A good portion of my job is spent on my knees, sucking people off to keep them happy.” Politics is all about suffering fools — if it’s for a good cause.

We’re 10 weeks out. Who will emerge as the crime-fighter and the get-shit-done-in-chief?

![]() MORE ON THE MAYORAL ELECTION FROM THE CITIZEN

MORE ON THE MAYORAL ELECTION FROM THE CITIZEN