This was going to be a column that could practically write itself. Two things happened after the tragic, broad-daylight murder last Sunday of Temple student Samuel Collington that would have made this a policy screed indistinguishable from past rants in this space, and led to a series of pointed questions:

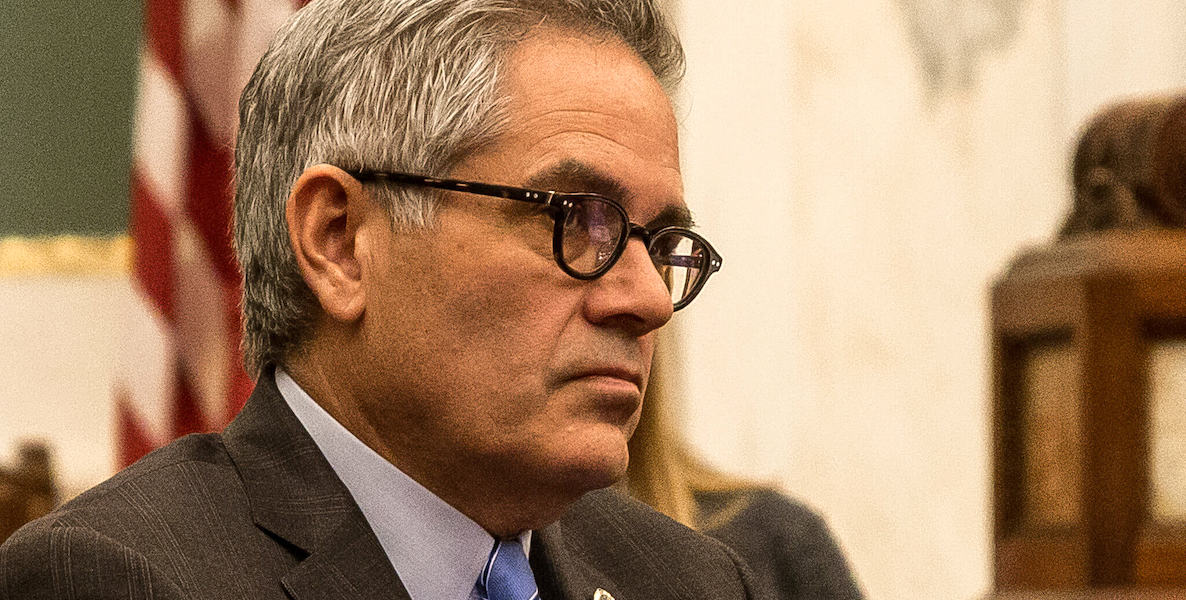

Where’s the outrage over what Police Commissioner Danielle Outlaw has described as our DA’s “revolving door” system of justice? Where’s the progressive concern for a homicide rate that’s approaching an 80 percent increase since Mayor Jim Kenney took office, and for a 45 percent drop in gun convictions since District Attorney Larry Krasner came on the scene?

Where’s the funding for a professionally-managed focused deterrence law enforcement program, like the one in Boston that helped cut homicides by 80 percent? Where’s the army of credible, street-level violence interrupters that, as we’ve shown, has helped stem gun violence in Oakland? Where’s the level of cooperation between cops, prosecutors, mayors and key stakeholders, as has been so successful in two nearby cities that have turned the corner on shootings and murder—Camden and Chester?

When teenagers are killing on our streets like they’re avatars in a video game, you’ve got to ask, even while holding them fully accountable: What can all of us do better—our institutions, yes, but also ourselves, personally?

The first news that set me off along these lines was the report of the lengthy rap sheet of Collington’s alleged killer. According to reporting by Ralph Cipriano at bigtrial.net, at all of 17 years old, Latif Williams had previously been arrested four times since he was 14, including recently for armed carjacking. In each case, Krasner’s office dropped all charges against Williams, who police say is also a suspect in four other nearby carjackings.

Then, as if on cue, came Krasner’s public remarks advertising his own cluelessness and unfitness for office. “We don’t have a crisis of lawlessness, we don’t have a crisis of crime, we don’t have a crisis of violence,” he said. Krasner’s tortured argument hinges on the fact that rape, residential burglaries and non-firearm robberies are actually flat or down, but it’s absurd on its face to argue there’s no violent crime crisis when murder, aggravated assault, nonfatal shootings, robbery, and nonresidential burglary are all considerably higher under Krasner’s ideologically-driven reign.

It was enough to make you channel your inner John McEnroe: You. Cannot. Be. Serious. On Thursday, after heated backlash, Krasner tried to clumsily walk his comments back, chalking them up to inarticulateness. Of course, the episode was just the latest in a string of Trump-like attempts on Krasner’s part to evade responsibility for the worst murder rate in Philadelphia history—a record 524 dead this year.

Because, apparently, there’s no sitting mayor to channel the public mood and turn dumbass comments like Krasner’s into teachable moments, the task fell to a former mayor, Michael Nutter, who eviscerated the DA in the Inquirer:

“I have to wonder what kind of messed up world of white wokeness Krasner is living in to have so little regard for human lives lost, many of them Black and brown, while he advances his own national profile as a progressive district attorney,” Nutter fumed. “I’d like to ask Krasner: How many more Black and brown people, and others, would have to be gunned down in our streets daily to meet your definition of a ‘crisis’?”

RELATED: See Mayor Nutter speak at our upcoming Ideas We Should Steal Festival

And what was the reaction of our incredibly shrinking sitting mayor? “I’m not going to get involved in a back-and-forth between a former mayor and the DA,” profile-in-courage Jim Kenney said.

So I was about to write all this—diving into the tragic Collington murder as a signpost for all that has gone so terribly wrong in the state of our leadership of late. And everything I would have written—all that I summarized above—would have been dead-on. But maybe it also wouldn’t have been the whole story. And that got me thinking about the nature of the stories we tell ourselves, and how that needs to become fuller and more humane, while not sliding into moral relativism.

Suddenly humanized

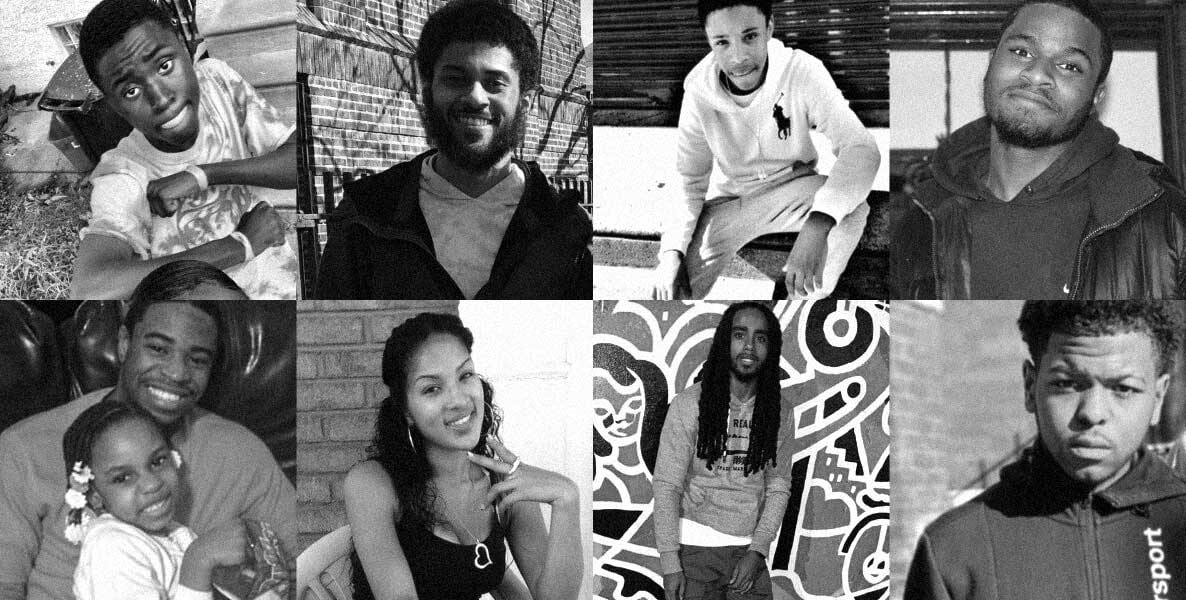

I was led to this rumination after catching footage on CBS3 of Williams turning himself in to police. The video stopped me cold. There, just outside police headquarters, Williams veers off into the arms of family and friends who embrace him with prolonged hugs before he’s off to face his fate.

In that grainy clip, this alleged shooter was suddenly humanized: He loves and is loved, a realization that only magnifies the tragic nature of this story. In the coverage this week, we learned of Collington’s commitment to criminal justice reform, and we heard from his family, for whom our collective heart grieves.

But there’s been precious little about his alleged assailant, save for that footage, which, for me, leads to all sorts of questions. How does a 17-year-old become a person who would carjack and shoot another? What hurt drives the hurt he may have inflicted? What institutions have failed him? Family? Church? School? Criminal justice system?

In his book A Time To Build: From Family and Community to Congress and the Campus, How Recommitting to Our Institutions Can Revive the American Dream, author Yuval Levin argues that case studies like the one that took place in North Philly last Sunday are really emblematic of a wider phenomenon: the erosion of our institutions, which he defines as “the durable forms of our common life.”

“We aren’t just loose individuals bumping into each other,” Levin writes. “We fill roles, we occupy spaces, we play parts defined by larger wholes, and that helps us to understand our obligations and responsibilities, our privileges and benefits, our purposes and connections. It moves us to ask how we ought to think and behave with reference to a world beyond ourselves: Given my role here, how should I act?”

Krasner is right when he talks about poverty as a root factor in crime; it’s just that he doesn’t do so to problem-solve so much as to absolve himself.

When institutions lose their power to influence behavior, Levin holds, the result is an ever-widening gap in the disbursement of social capital. When that happens, chaotic scenes from our streets defying long-held communitarian norms become the new norm.

This in no way is meant to excuse what Williams is alleged to have done here. If guilty, he should be held fully accountable. But it is to suggest that when Williams attacked Collington and the two wrestled on that North Philly street last Sunday, the story was really about much more than the facts of those frenzied moments, the intricacies of criminal justice policy, or the piss-poor leadership we’ve gotten of late. It was also about a lack of context in the way we talk about our social ills.

Once, a criminal defense attorney walked me through the everyday landmines her clients face. Before talking about the facts of their particular case, she’d ask them a series of questions meant to elicit the extent of their trauma: Have you been abused? Have you lost loved ones to gun violence? How often have you gone to bed hungry? (Talk about missing context: How many know that poverty is considered $21,000 in annual household income for a family of four?)

Invariably, the answers come back in the affirmative. No one is unscathed. So Krasner is right when he talks about poverty as a root factor in crime; it’s just that he doesn’t do so to problem-solve so much as to absolve himself. I’m not doing the bleeding heart thing here; I’ve written often about our need to incarcerate those—but only those—truly in need of serious prison time.

But by all accounts, younger and younger Philadelphians are engaging in more and more violence of late; nihilism is at an all-time high. It is folly to think that’s not connected to the opportunity deserts that pass for our streets, and our unwillingness to really see characters like Williams when we talk about crime.

Which gets us to another institution, and its role: the press.

Turns out, conventional wisdom in the moment is often wrong

“The power of storytelling is exactly this: to bridge the gaps where everything else has crumbled,” novelist Paulo Coelho once observed. If you agree that, in a city of great divides, perhaps the gulf is greatest between the hopeful and the bleak, then that which is as old as our history—storytelling—ought to be part of the cure. Yet our newspaper stories, Twitter posts, TV clips and even our own lives tend to feature cartoon-like characters, assumptions about the motives of others, and knee-jerk judgment, rather than wide-eyed wonder and curiosity.

I’ve been thinking of this lately, because more and more, the veracity of commonly-accepted narrative seems to be being called into question all over the place. Have you watched Get Back, the stunning six-hour documentary inside the Beatles last recording session 52 years ago? It’s a truly inspiring work. I can’t stop thinking about it. In part, that’s because it’s one of the most intimate windows ever into the mysteries of the creative process. We’re along for the ride as these four “lads” joyfully goof off together; at one point, their producer suggests they ought to, like, try to master a couple of songs, but Lennon and McCartney just keep acting silly together. That’s when you realize what they know: That art is the product of such wildly abandoned joy.

If we don’t look fresh at our till-now-intractable problems and figure out new ways to talk about them, we’ll just get more of what we’ve gotten.

And it is that visceral, palpable sense of pure freedom that is so stunning, because for decades the conventional wisdom held that, by the end, the Beatles hated one another. Yet here they are, in the flesh, clearly in love. “We’re like lovers,” Lennon even jokes with McCartney at one point. How did the press and history get it so wrong for so long? Even McCartney, after viewing the film, conceded in the pages of The New Yorker that he’d bought into the spin that his relationship with Lennon had been stormier than it was.

Or how about Isabel Wilkerson’s beautiful The Warmth Of Other Suns, a narrative of the biggest story of the 20th century that was also the most overlooked: the Black migration north, a trend altogether missed by the white mainstream press? Hell, even last year’s pandemic blockbuster, The Last Dance, gave us a fresh look at Michael Jordan—more nuanced and more likable than in his heyday. Turns out, conventional wisdom in the moment is often wrong.

How does this relate to the scourge of gun violence in our city? If we don’t look fresh at our till-now-intractable problems and figure out new ways to talk about them, we’ll just get more of what we’ve gotten. That’s what Jo Piazza did so wonderfully in our gun violence podcast, Philly Under Fire. It was storytelling as the antidote to alienation.

Whether or not Latif Williams is found guilty of Samuel Collington’s murder, isn’t that really what this story, and so many like it in our city, boils down to? Somehow finding a way to dull the edges of the alienation too many among us still feel and live with everyday?

There’s plenty of time to bemoan the sorry state of our leadership. But when teenagers are killing on our streets like they’re avatars in a video game, you’ve got to ask, even while holding them fully accountable: What can all of us do better—our institutions, yes, but also ourselves, personally? Because what is a city if not a common project among a disparate, diverse bunch of individuals?

![]()

RELATED

Header photo of Larry Krasner courtesy Philadelphia City Council / Flickr