Ever get that feeling, halfway through a movie, that you’ve seen this story before? Well, that same sense of déjà vu regularly characterizes our civic life. At a West Philly YMCA last week, State Senator Tony Williams convened what was billed as a “gun violence summit.” Governor Tom Wolf, Mayor Jim Kenney, Attorney General Josh Shapiro, and Police Commissioner Danielle Outlaw all attended in order to talk about the work they otherwise might be doing.

“I’m tired of going to these fake meetings where we have community meetings, we listen to input, and we go away and nothing happens. This is about action,” Williams said. And then…amid the cacophony of soundbites, not one new action was proposed.

More on the Philadelphia district attorney candidates

What’s so frustrating about Philly’s scourge of gun violence—which predated the pandemic—is that we know what works to combat it. Listen to our deep dive podcast from the gun violence epidemic frontlines, Philly Under Fire, and it’s plain as day. We might just feel like someone is on the case if the elected officials who had gathered last week in West Philly came out of that YMCA and, eschewing retread talking points, announced that they were on the same page and would immediately be implementing three policy changes: turbocharging focused deterrence and cure violence policing citywide, and fully funding and rolling out ABLE (Active Bystandership for Law Enforcement), an innovative peer leadership training program that changes internal police department culture for the better.

Instead, we got more pablum, like this leading-from-behind gem: “I think we’re all looking for answers,” said Governor Wolf. “We’re starting with a process, but I think the reason I’m here is to make sure once again that I stand ready.” Wolf fiddles while Philly burns.

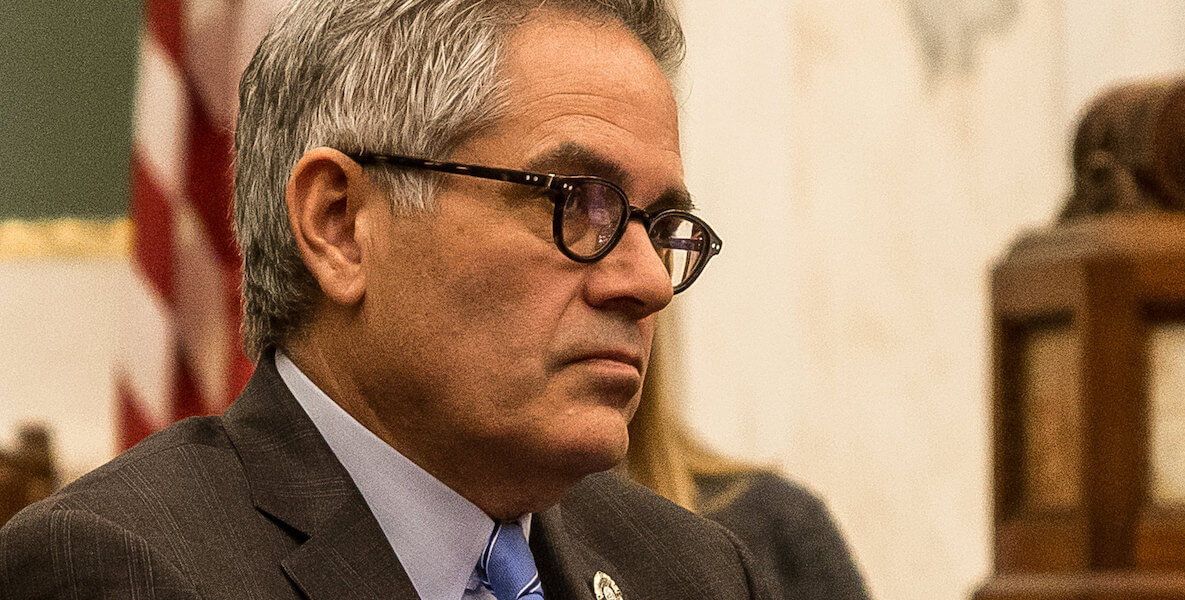

But Woody Allen once said that “showing up is 80 percent of life.” At least Wolf and the others did that. Noticeably absent from the soundbite fest was District Attorney Larry Krasner.

Now, maybe Krasner realized it was just going to be a photo-op, and he wasn’t about to play that game. But there is still value in the city’s chief prosecutor appearing with those he should be working with in order to effectuate change. In his very good new book, For the People: A Story of Justice and Power, Krasner positions himself as a crusading changemaker. Well, Jesse Jackson used to say there are jelly makers, and there are tree shakers. Which one is Larry Krasner? An outsider, shaking trees, someone who agitates for agitation’s sake, as when he points the finger of blame at Outlaw or Shapiro? Or someone who, for the last four years, has sat at the insider problem-solving table and delivered on much-needed systemic reform?

“Our streets are less safe”

Certainly, Krasner’s 2017 diagnosis—which he cogently lays out in his book—was much-needed. Cash bail and the probation and parole systems are unjust. We do have a broken criminal justice system that has fueled racism and historic divides between the haves and have-nots. But Krasner has been D.A. for four years now. Have his policies helped to repair that breach? He deserves credit for the exonerations of 19 wrongfully convicted inmates and for cutting the city’s probation rolls by a third.

But our streets are less safe while, ever the tree shaker, he picks fights with the cops and the attorney general and the U.S. attorney.

Just how much of a systemic reformer is Larry Krasner? Let’s look at what, elsewhere, has become a critical tool in a reformer’s kit, the use of diversion programs. Diversion allows low-level defendants to avoid criminal charges if they follow a prescribed program set out by a prosecutor or judge, diverting them from the criminal justice system. Conditions can include classes, community service, drug treatment, mental health counseling, and restitution. Upon the successful completion of a diversion program, a defendant is rewarded with a clean record.

Some diversion programs have flaws—like charging defendants fees—but their goal is to address the root cause of crime, something Krasner has long called for, and to offer some relief to overburdened courts and crowded jails. According to the Center on Media, Crime and Justice at John Jay College, the program in Cook County, Illinois, for example, doesn’t charge fees or require participants to plead guilty. A year after finishing felony diversion, 97 percent of graduates have no new felony arrests, and 86 percent have no new arrests of any kind. The program’s drug school saves the county an estimated $1.5 million annually.

On Krasner’s public data dashboard, the district attorney sings the praises of diversion: “We are increasing the use of diversion and working on improvements and expansion to diversion that we hope will improve employment, address addiction, reduce domestic violence, support our veterans, increase education, lift up children and their families, and reduce government waste.”

Spoken like a true reformer, but do Krasner’s actions match his rhetoric? According to the district attorney’s own data, the number of cases the D.A. has referred to diversion has declined by 80.4 percent since he first took office. As a result, many of the city’s diversion programs have essentially been starved to death by the Krasner administration.

Let’s take the Accelerated Misdemeanor Program—AMP—under which non-violent first time offenders don’t enter a plea. They perform community service or a dependency treatment program and pay court costs; upon successful completion, their records are expunged.

“This was a great program that got a lot of people the help they needed,” a former ADA under Krasner told me. “In Kensington alone, we’d see a hundred cases a week. We’d connect them to drug counselors in the courtroom. But Larry is more interested in just not prosecuting than he is in using the carrot and stick approach of diversion to actually help people.”

Or take Project Dawn Court, which connects non-violent repeat prostitution offenders with therapeutic and reentry services. A defendant’s plea is held in abeyance while she undergoes a program that includes treatment for sexual trauma and drug addiction, when applicable. Upon successful completion, the prosecution is withdrawn. “There would be Dawn’s Court graduation ceremonies in the courtroom, and it was a beautiful thing,” the ADA, who requested anonymity, told me. “Girls would be clean and reunited with family members and on their way to employment. Now you go up to K & A and see these girls walking around like zombies.”

Despite citing statistics on its website attesting to the efficacy of programs like Project Dawn Court, the D.A.’s office makes no bones about having deemphasized, and in many cases, gutted its own diversion programs.

“The Small Amounts of Marijuana (SAM) program has been effectively shut down because the DAO no longer considers it a good option,” spokeswoman Jane Roh emailed me. “Same with Project Dawn Court for people arrested on sex work-related offenses; the DAO has not referred anyone to Dawn Court in at least two years. Approximately two-thirds of arrests related to erotic labor are declined for charging by the DAO.”

Also on its last legs is the Sexual Education and Responsibility (SER) program, aimed at non-violent offender men who patronize prostitution. In lieu of probation or community service, defendants attend a one-day seminar that delves into the ways prostitution exploits and victimizes women, their families and the community. Upon successful completion, the prosecution is withdrawn.

Roh confirms that referrals to diversion programs are way down, in part because the rate of “declinations”—the refusal by the DA’s office to file charges after an arrest is made—is so high. Less charges equals less opportunity for diversion, in other words. But whatever happened to progressives wanting to help people who are victims of drug addiction or sex trafficking and are caught up in the system?

Alternative Reform Options

Roh says that ADAs have the option of withdrawing all charges for some drug offenses when proof of treatment is provided, but that ignores the reason diversion programs were created in the first place: Because, often, addicts are loathe to enter treatment on their own. If the system mandates it, however, using the threat of prosecution as an inducement, the chances of turning a life around grow exponentially.

“The MacArthur Safety & Justice challenge found significant racial disparities in fines and fees associated with diversion levied on defendants prior to 2018,” Roh writes. “The DAO has simply stopped supporting diversion programs that are unfair and set people up to fail, and is focusing on working with system partners to create more evidence-based diversionary programs that show promising results in other jurisdictions, such as restorative justice.”

Okay, but we’re four years in, and you’re just now starting to work on alternative reform options? Here we really get to the heart of the matter. A reformist D.A. who sings the praises of diversion on his own website might just notice the flaws in his own system and, I don’t know, fix it. Maybe do as Chicago did and eliminate fees.

This raises the question: Is Larry Krasner able to deliver systemic change? Or does he just talk?

It’s easy to, pundit-like, shake trees. Krasner’s shoot-from-the-hip cowboy style will certainly endear him to those loyalists who chanted “fuck the police” at his election night victory party four years ago. (Which Krasner reacted to by defending their First Amendment rights). But it’s infinitely harder to work with other stakeholders to make change happen.

Signs that Krasner didn’t have the political chops or people skills necessary for reform emerged early in his tenure. Marian Braccia, who was the Assistant Chief of Charging and ran the Domestic Violence Diversion program under Seth Williams and Krasner and is now a professor at Temple University, attended one of his first Criminal Justice Advisory Board meetings. It was one of the first times Krasner had been in a room with then-Police Commissioner Richard Ross, and he announced that his office would be declining to prosecute a lot more of Ross’s arrests than his predecessor had.

“Is that the time to disclose that to the Commissioner?” asks Braccia, who is not a critic of Krasner’s agenda. “Is that the place to do it? Or do you talk directly to the Commissioner, so you’re on the same page? I’d say to Larry and his team, I’m a process person. You tell me what you want done, I’ll tell you who we need around the table, what stakeholders we need to work with. And it fell on deaf ears. Larry had an agenda, but he held it so close to his vest that it wouldn’t even be shared within his own administration, which just makes it harder to get things done.”

Shea Rhodes makes a similar point. She was one of the founding ADAs of Project Dawn Court and is now the co-founder and director of the Institute to Address Commercial Sexual Exploitation at Villanova University’s Charles Widger School of Law. She is quick to praise one of Krasner’s ADAs for pushing through Vacatur Petitions—legal recognition that convictions should never have happened in cases where crimes were committed while defendants were under the control of human traffickers.

But Rhodes has also seen how, on a practical level, Krasner hasn’t been up to the task of enacting systems change. It’s not enough that Krasner is no longer prosecuting prostitution when the police are still making prostitution arrests, she says. She recounts case after case where a defendant is suffering from active drug withdrawal while in custody. The D.A.’s office will eventually decline prosecution, but, after many hours, the defendant will still not have been handed off to social services. “That’s because the Krasner administration didn’t bring law enforcement to the table with them,” she says.

Thomas Mandracchia was one of Krasner’s new ADA hires out of Penn Law in 2018, and is now in private practice in Wilmington, Delaware. “Both progressive and old school prosecutors alike are fed up and miserable in Krasner’s office,” he says. It started with the training in progressive prosecution program new hires were subject to—an innovation the Citizen praised in 2018. It was led by former Boston prosecutor Adam Foss, who is currently being investigated on allegations of sexual assault.

“Rather than a rigorous training program for us new prosecutors, my class’s training was a cross between a graduate seminar and a religious retreat, filled with lectures followed by group reflection circles,” Mandracchia says. “Our bizarre training ended and, as we eventually entered the courtroom, my colleagues and I realized our training was insufficient at best and misleading at worst. Foss had instructed us to do with our cases what we wished, even going so far as suggesting we evade or disregard supervisor oversight. Foss’s suggestion misled some members of my class into believing they had authority to unilaterally withdraw felony charges in their first few weeks in the courtroom. And this poor training was not limited to new hires. Attorneys at all levels complained about lack of training.”

Like so many others I’ve spoken to, Mandracchia hits on a theme. It’s not Krasner’s beliefs that are a danger so much as whether he can competently administer justice. Take just one utterly heartbreaking case. In October 2018, police arrested Michael Banks, who had a long record, for a felony gun violation. Four months later, Krasner gave Banks a plea deal of 3-9 months in jail. Banks was back on the street in no time and promptly shot 7-year-old Zamar Jones in the head as he played with a toy on his family’s porch.

Over the past week or so, we’ve published dueling guest commentaries from the two candidates for District Attorney. Carlos Vega and Krasner have both accused the other of, essentially, lying. And they’ll be debating next week, so there likely will be more such noise. As I read the allegations they hurl at one another, I can’t stop thinking of Zamar.

This I know: We need a smarter discussion about reform, one that holds the safety and rights of someone like Zamar at its philosophical center. Is that a system that offers a helping hand to those caught in cycles of prostitution and drug addiction? That decarcerates, while also keeping those who would terrorize Black and Brown communities away from our kids?

Maybe most of all, amid a murder epidemic that ought to have us all questioning every practice that has gotten us here, the most critical question facing the city is this: Who has the skill set and inclination to do the hard work of actually delivering that system to us?

Make sure you’re all set to vote in the 2021 primary election in Philly

- Our voter guide lays out everyone who’s running for office and more

- Here you can learn about all the judges who will be on Philly ballots

- Have questions about voting? Find answers in our PA voting FAQ.

- Make sure you’re registered, apply for a mail-in ballot and more