![]() Someone has slit in half the 30-foot-long Black Lives Matter banner outside our St. Luke and the Epiphany. For the second time.

Someone has slit in half the 30-foot-long Black Lives Matter banner outside our St. Luke and the Epiphany. For the second time.

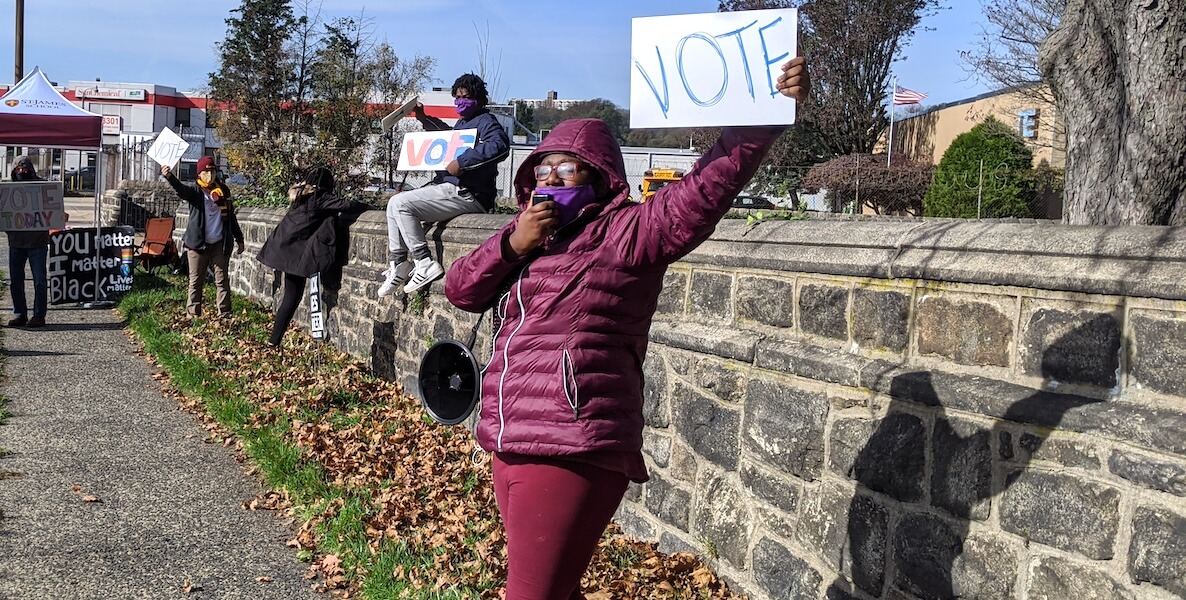

This summer, four of our #VoteThatJawn interns danced a TikTok in front of that banner. I videotaped them with my phone from across the street. Cars passed between us, and they looked very like they were in a movie. It felt like a movie. One girl was still in high school, one in community college, West Chester University, and UPenn. Different young bodies, moving, because youth is movement and freedom is movement.

The song they danced came from a slogan that Kamryn, in the yellow West Chester sweatshirt, had chanted at a voter registration drive earlier that summer. It spoke of voting and voice. So did the energy of their legs and arms.

This was the new life they were bringing to the electorate, sickened with Covid, angry, stuck in the ditch where lies have driven so many arguments, distracted. All summer Jawn interns created infographics; hosted lectures; registered voters; put up tiny little Instagram Lives that garnered lots of viewers afterward.

Talented, generous older folks and the church had backed them up, with money, bookkeeping skills, mentoring, word and music editing, choreography, you name it. When I’d watched them, masked, young, beautiful, caring for each other after a summer of mostly virtual work together, I loved them.

The banner stretched along the brick wall, underneath white columns and next to Tiffany windows. Inside hang portraits of an abolitionist rector as well as more than one who, like parishioners, had benefited from the enslaved labor or even the sale of Black people. Block yellow letters against a background of slate-grey pebbles said that despite the hidden shit-show of deadly oppression underneath American success, these parishioners have heard the message: “Whatsoever you do to the least of these, you do to me.”

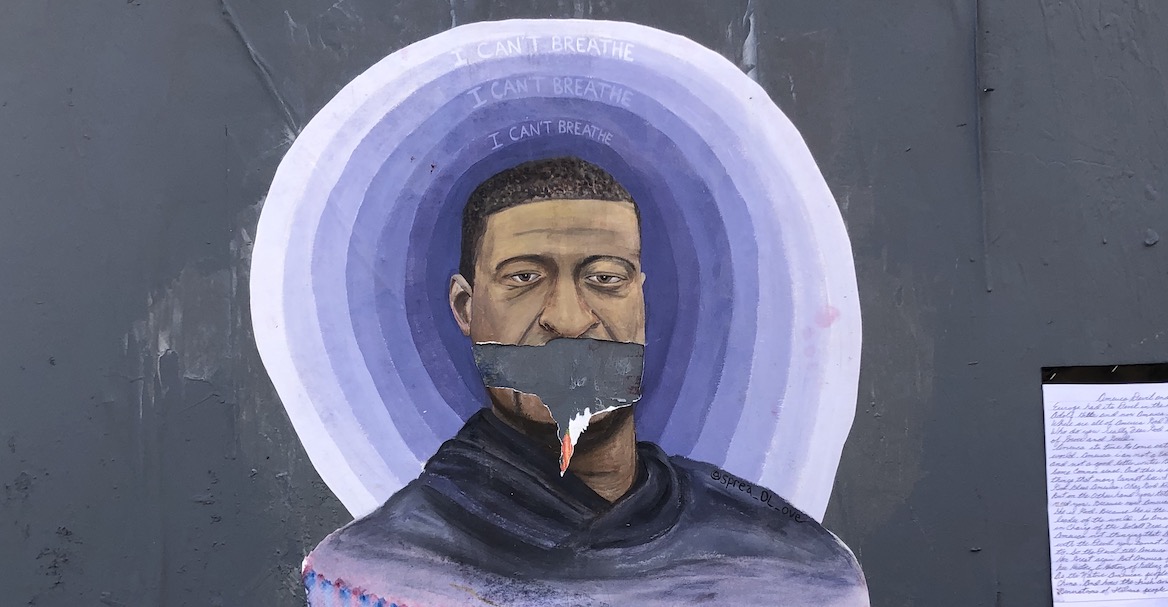

If Black Lives Mattered ultimately, why, then, we could not bear, as a culture, to accept the obscene commonplace of these snuff videos at dinnertime where our children can see them as surely as the children who were taken to lynchings.

Translation for America: Whatever you do, have done, want to do, or imagine doing to Black people, you’ve done to Jesus. Or humanity. Or your mother. That goes for what the stories we tell, and the images we watch. And the shame that addicts America to screening and sharing and watching more and more Black death.

Because, just think: We do not see white people, real live people, suffocated through the better part of a full minute on the television news. See it over and over and over until we cry or puke or wall off our broken hearts. We do not see white boys walking away from police and shot over and over over in the back while a ring of officers watches without objection.

![]() If we could imagine the sacred in each person, if Black Lives Mattered ultimately, why, then, we could not bear, as a culture, to accept the obscene commonplace of these snuff videos at dinnertime where our children can see them as surely as the children who were taken to lynchings. We could not so easily use those 100-year-old lynching photos of our ancestors’ bodies as props or shorthand storytelling in documentaries, on television, and social media pouring black death through our phones.

If we could imagine the sacred in each person, if Black Lives Mattered ultimately, why, then, we could not bear, as a culture, to accept the obscene commonplace of these snuff videos at dinnertime where our children can see them as surely as the children who were taken to lynchings. We could not so easily use those 100-year-old lynching photos of our ancestors’ bodies as props or shorthand storytelling in documentaries, on television, and social media pouring black death through our phones.

If even Black Lives Matter, then the project of democracy has a shot, the constitution and creeds, justice and mercy, the expansion of voting rights in the last few decades; we’ll have a chance. We will not have to throw Black Lives away to achieve so-called unity, as the U.S. has done before, and always about representation: when writing the Constitution, or at the bloody end to Reconstruction.

The young people in #VoteThatJawn, Asian, white, Latinx, Black—they believe, as young registration evangelist Sheyla says, that we can “re-imagine, or re-create” representation. They communicate it to each other. It’s why watching the interns in front of the banner always gets me.

If Black Lives Matter, then so do the issues the students call existential: climate change, racial injustice, and economic inequality, which has grown in this country since the 1970s marked the end of the great middle-class expansion. Voting rights and elections in the 2020 pandemic—all this was also about life and death, and Black Lives.

And then, someone slit the banner, right the way through.

The sexton took it down, and we repaired it, with Gorilla tape on the backside, six or eight inches at a time, matching each letter carefully, like my grandmother taught me to match plaids at the seam. It looked awfully good.

Now, someone has slit it again. As my husband asks in his sermons: What does it mean?

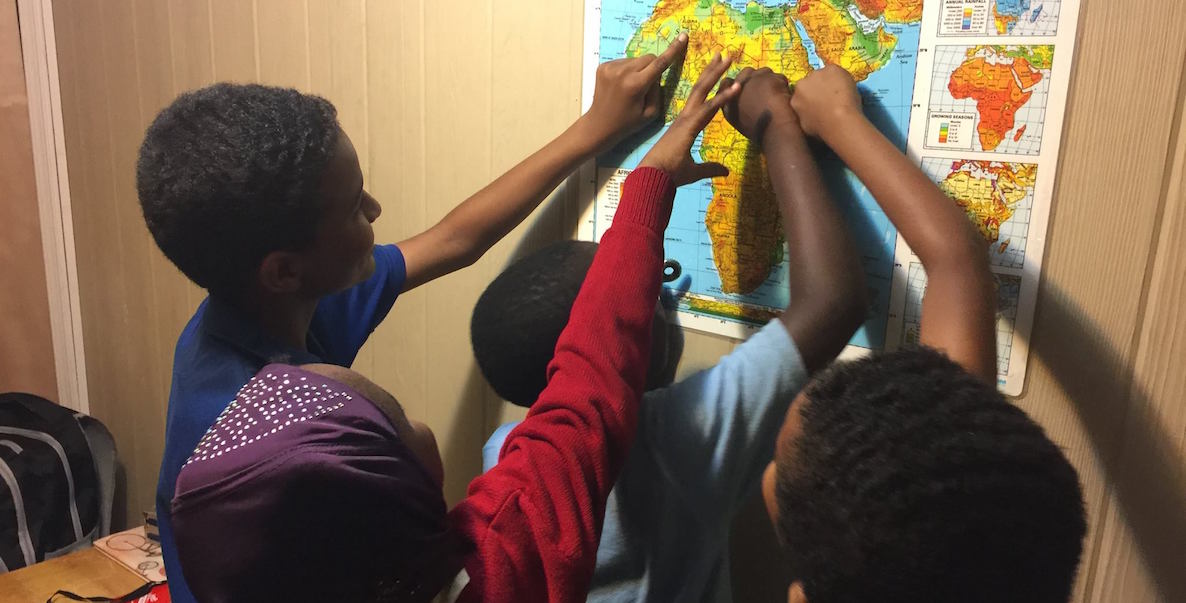

![]() Welcome to the Blackside, where resilience is required, although seldom sufficient. The ancestors told us to make a way out of no way, with faith and thanksgiving. And they did, and we’re here, with passionate, dancing young people in the sunshine and someone slitting the banner in the dark.

Welcome to the Blackside, where resilience is required, although seldom sufficient. The ancestors told us to make a way out of no way, with faith and thanksgiving. And they did, and we’re here, with passionate, dancing young people in the sunshine and someone slitting the banner in the dark.

I’ll ring the sexton, and we’ll get onto our knees with our masks in the parish basement, and patch it again. And the church will make a new campaign to talk, connect, reach out even more. Scripture says: “The stone that the builders rejected has become the chief cornerstone.”

Lorene Cary is a lecturer at Penn and author, most recently of Ladysitting: My Year with Nana at the End of Her Century, a care-taking memoir, and My General Tubman, a play about the complex journey of the abolitionist/activist that ran this year at Arden Theatre. She is the founder of #VoteThatJawn, the initiative to register and engage young voters.

Photo by Gabriela Thomas