The guys outside Victor Floyd’s new house on North 17th Street in Nicetown were clearly up to no good. Floyd — a 64-year-old grandfather of three, who’d just bought his first house — watched the young men selling drugs and shooting craps on his stoop. When he confronted them, they threatened to kill him.

“This is our house,” they told him. “You’re not from the neighborhood.”

Floyd says he went to the local police station several times, but they told him they could do nothing, unless something actually happened to him — which, he notes, “felt a little after the fact.” Frightened and frustrated, he saw how this would likely play out: “I’m striving to do right,” he says. “I’ve been through the gang war era. I don’t have time to spend in jail. But I knew it was either kill or be killed.”

Then Floyd saw a news story about Philly Truce App, a project launched in early 2021 by Mazzie Casher and Steven Pickens, high school friends, now in their 40s, who are on a mission — as their tagline says — to reach “Zero Homicides Now.” Their not-quite-two-year-old app has received about 200 calls so far, ranging from help of the sort Floyd needed to mediating beefs between teenagers. They also organize town watches; hold school assemblies and rallies; and, every May, throw an annual Truce Day celebration.

Through the app, Floyd got in touch with, and told his story to, Casher. A few days later, after he did some calling around, Casher got back to Floyd with info about two neighborhood guys with influence and standing in the community. Those guys, in turn, talked to the young men harassing Floyd — and got them to move on.

“Calling those influencers was thinking out of the box,” Floyd says. “They intervened on my behalf to try to protect me and find a resolution for me. That there is honorable and I can never thank them enough.”

A plan to help

Casher and Pickens met in 1988, during the “crack era,” when neighborhoods were devastated by the drug trade; two years later, in 1990, the city saw 500 homicides — a tragic milestone we hit again in 2022. Pickens, a firefighter, has lived here his whole life; he’s married to the sister of Casher’s first wife. Casher, who has been a touring hip-hop artist, playwright and truck driver, lived in Los Angeles and North Jersey for about 12 years, before moving back in 2021. He’s the storyteller of the pair.

They ran into each other in late 2020, as the number of killings was on a steady rise. Like the rest of us, they’d watched the racial uprisings that flared after a White policeman killed George Floyd, who was Black. What they didn’t see was a similar outrage over the intraracial murders in their community. “People seem to be just accepting homicides,” Pickens says. “I couldn’t understand why there were not more Black men moving with a sense of urgency and concern about this issue.”

They came up with the idea of Philly Truce App soon after, partnered with a software engineer and launched in May, 2021. It works like this: Someone in need of help fills out a form on the app. That pings volunteers who are logged in; a volunteer then reaches out, makes sure the client is safe, and then sets up a call. That first call is to fill out an intake form, with details about the client, the neighborhood, the issue, and what is needed. Casher and Pickens then review the information and devise a plan to help.

At first, the men worked with the Black Male Community Council of Philadelphia, a Nicetown-based violence intervention group, which gave Philly Truce volunteers mediation training. Many of those volunteers faded away over time; now, most of the intervention work is done by a handful of people, including Casher and Pickens themselves. People who sign up to be intake volunteers are trained on what to do through a video; they are not screened, and they do not receive any trauma-informed training. So far, the project has been fairly informal — what Casher calls “unofficial R&D” — with word spreading through media (they are good at sharing their story) and participants waxing and waning over time.

Now, the partners are getting ready to launch a new iteration of their app, thanks to a partnership with Code for Philly, which held a hack night last week dedicated to their project. Casher says they hope to make it easier for clients to convey their issue the first time they log in, perhaps with an in-app voice recording; make capturing demographic and other basic info more seamless; and find a way to create more community on the platform.

Philly Truce raised about $20,000 in 2021 and about $27,000 in 2022, which they spent on stipends for their volunteers, flyers and other materials, and to throw an annual event to raise awareness.

“People seem to be just accepting homicides,” Pickens says. “I couldn’t understand why there were not more Black men moving with a sense of urgency and concern about this issue.”

Both Casher and Pickens, like so many Philadelphians, have always known people affected by gun violence. Right now in Philly, Casher says, is like always in Philly: “We’ve averaged 350 murders a year over the last 50 years,” he says. “I remember hearing at 15, in 1990, about the 500 homicides. It didn’t land on me in any particular way — it’s just where I lived.” Replace crack with social media and gun notoriety, he says, and you have the same story (except, maybe, younger). One reluctant 13-year-old boy they recently worked with, who’d been shot in the foot, is a window into the nihilism the men encounter: “He said, If I get shot, I get shot; if I die, I die,” Casher recalls. “We’re trying to convince him that’s not how it should be.”

For Pickens, the work turned especially personal in October, when his daughter’s fiance was murdered; he left behind their son, Pickens’ grandchild. “I was already two years into the work before it came really close to home,” he says. “But I always felt a sense of sympathy, even before that.”

“Zero Homicides Now”

Several months after they launched the app, Philly Truce took to the streets for a far more old-fashioned mode of violence interruption. Along with two West Philadelphia congregations, they started Peace Patrol, walking in groups through several neighborhoods, passing out flyers about Philly Truce, knocking on doors and talking to people, being present.

The first Peace Patrol was Thanksgiving weekend in 2021. In the beginning of last year, they started a more sustained campaign of walking the streets on weekends, on six different routes, from January to April. Casher says compared to the 100 days before they started and the 100 days after, shootings seemed to go down. (A similar experiment this fall was less successful.)

“If people are out there, you think twice about doing stuff,” Casher says. “Even if it’s three guys standing on the corner, doing what they’re doing. When six guys walk up with safety vests on, grown men, doing something that looks official, they’ll leave the corner. That’s good for 30 minutes, but it all adds up.”

Pickens and Casher don’t work in the vein of traditional violence interrupters, getting in front of volatile beefs to calm a situation down. Most of the time, the issues their app encounters are situations where a nuanced approach to solving a problem is called for, like an older woman being harassed by an ex-lover, an ongoing dispute over parking or escalating aggression over neighborhood issues — the kinds of things that can turn violent if they are not solved early.

Their larger mission is an aspirational goal of “Zero Homicides Now” — something that requires everyone leaning in to the issue of gun violence. To that end, their media savvy — helped by Casher’s entertainment background — is a bonus. Even before they got off the ground, the duo was cultivating the press, and they have garnered attention from all corners for their work. To wit: Last year, City Council proclaimed May 8 “Philly Truce Day” in honor of the group, which threw a carnival in North Philly with live entertainment, motivational talks, a parade, and youth fashion show.

This year, Philly Truce is launching a “Safe Cities Summit and Curriculum”, scheduled to run May 8 to June 12, which will use as its basis three historic Philly programs they say reduced violence: House of Umoja’s NO GANGWAR IN ‘74 Campaign, which crafted peace treaties that reduced homicides by 28 percent; OIC’s Feeder Program from 1964, which provided skills training for 4,000 citizens; and the Urban League’s Our 4 Good reentry program, which has placed 374 returning citizens in jobs, with a 0 percent recidivism rate.

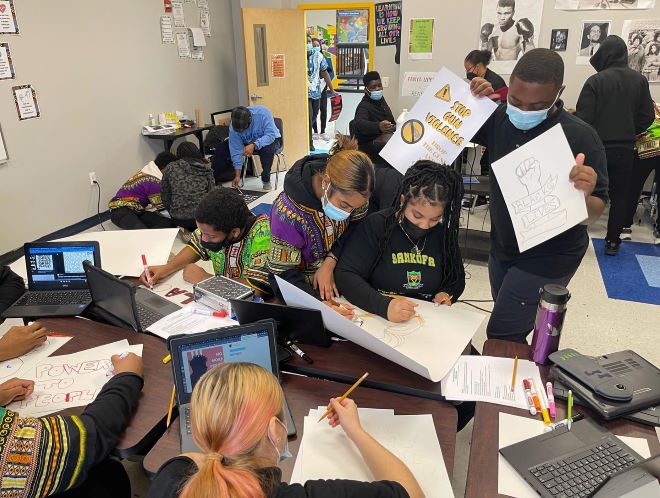

They also host school assemblies, in partnership with Intercultural Family Services, that strive to teach students the difference between “snitching” and helping, and to understand how music and video can affect attitudes and behaviors, using a film they created called It Starts In The Home. So far this year, Philly Truce has done about six middle school assemblies, with several more planned for the spring.

As with most of Philly Truce’s programming, it’s Casher and Pickens — sometimes with their wives and a couple of volunteers — who are on stage, doing the work.

This alone is not enough, of course, to halt the shooting spree that plagues Philadelphia — or to solve the myriad problems that lead to it. That requires both community-level and government-level coordination, the type of efforts that have lowered violence in Chester, Oakland and Newark.

But Casher and Pickens recognize that it is not enough, either, to wait for that coordination to happen — they, like all of us, are responsible for making change.

“That’s a big part of what’s missing today,” Pickens says. “Even though this is affecting so many people, there’s a large number of people not making the connection that it shouldn’t be happening to anyone. That’s why we’re here.”

![]() RELATED STORIES ABOUT REDUCING VIOLENCE IN PHILLY

RELATED STORIES ABOUT REDUCING VIOLENCE IN PHILLY