As analysis of the 2020 election rolled out over the last couple months, one of the most talked-about local trends was the uptick in votes for Pres. Trump in Hunting Park and other majority-minority wards of North Philly.

Read this story's key takeawaysCheat Sheet

At 66 percent, citywide turnout this year was the highest since 1984. But out of the city’s 66 wards, the 7th, which encompasses part of Hunting Park (the rest is in Ward 43, where turnout was also very low), was one of four to fall below 50 percent. (Two of the other three were where Penn and Temple main campuses are located, the low totals attributable to students voting elsewhere.)

Only 6,700 people cast ballots in Ward 7—a decrease of more than a thousand votes from 2016.

Heightened dissatisfaction with the state of the country amounted to some voters, in a Democrat-controlled city, swinging their vote to the embattled president; for so many more people it manifested as apathy about the prospect of voting altogether.

“You can’t go up to people who are barely surviving, barely living, and want them to participate in voting for the community,” says Vanessa Maria Graber of Philly Boricuas. “What do people really get out of voting for these candidates?”

“It’s not rocket science as to why people aren’t voting,” says Vanessa Maria Graber, co-founder of Philly Boricuas, a grassroots organization focused on the Puerto Rican community who spent months trying to get out the vote in Hunting Park and adjacent neighborhoods. “Take a walk through those neighborhoods and see how people are living, where people are really struggling financially as a result of the pandemic. People are also dealing with a lot of anxiety and depression as a result. They’re just trying to survive.”

Voter turnout in Hunting Park has been low for decades, and as Graber learned, none of the efforts to change that have so far made a difference. In part, that’s a reflection of broader issues like poverty, transience, a lack of opportunity, and a (in many ways understandable) negative perception of government services.

The story of voting in Hunting Park is replicated in many parts of Philly, and in cities around the country. Solving the puzzle of turnout, which means finding a way to empower every citizen to cast a ballot, requires understanding what keeps people from the polls—and how best to address those issues.

But first a little something about turnout numbers

Would you believe it if I told you that in 1960, turnout was more than 90 percent in the city and that was actually worse than how the city performed this year? Remember, turnout in 2020 was a celebrated 66 percent, with 749,317 votes the highest in nearly 40 years.

What YOU can do to helpDo Something

In 1960, turnout appeared extraordinarily high because only a smidge over half the city was registered to vote. In 2020, with more than two-thirds of the city registered, and a smaller population, the top-level numbers belie the fact that more of Philadelphia’s population actually voted in this past election (47 percent) than in the election of JFK (46 percent) in 1960.

Because of how we typically calculate turnout (as the percentage of registered voters who cast ballots), the gains we make in registration actually interfere with percentile turnout numbers, —which is ironic because registering new voters tops the list of most GOTV playbooks.

A dramatic example is the story of Ward 27 in this election. Bordering the Schuylkill River in Southwest, it’s where Penn’s main academic buildings and hospitals are located. When students vacated the area during the pandemic, an untold number did cast votes elsewhere in the country, but they still counted against local turnout in Ward 27.

Neighborhoods with more fluidity of population are disadvantaged by the way we calculate registration and turnout. It’s why neighborhoods with more renters have noticeably better voter-registration rates than areas with high homeownership areas despite the fact that renters are less likely to vote than homeowners.

What this means for Hunting Park is that, as with many facets of voting, the numbers don’t tell the whole story. Some 90 percent of eligible Hunting Park residents have been registered to vote in recent elections, including on November 3, according to data from the City Commissioners and population estimates from the Census Bureau. But how many of those registered voters still live in the neighborhood, where evictions, job scarcity and other reasons for turnover is frequent, is unclear.

“It’s a really difficult puzzle in any given election because there are very disparate neighborhoods with very disparate explanations of what could be driving turnout,” says Dr. Jeffrey Carroll, a political scientist at Chestnut Hill College. He’s one of the many researchers who’ll be digging into more of the 2020 voting data on a granular level in the coming months. “I think it’s still left in the air to see how this election lines up with the past.”

What we do know, though, is that turnout in Hunting Park is low in every election—and it remained lower than in comparable neighborhoods in 2020.

Hunting for votes in Hunting Park

The neighborhood of Hunting Park stretches over a massive area—bounded by Roosevelt Boulevard to the north, Broad Street to the west, and Front Street to the east—and includes the largest green space in North Philly, the 87-acre eponymous park. More than 90 percent of residents are Black and Latinx (of them, Puerto Ricans are the largest ethnicity).

Although the park was beset by littering, crime, and drug use in the 1990s, since 2013, it has received large grants to upgrade lighting, add a new baseball field, and prune and maintain the trees. The infusion of park funding—spearheaded by a $21 million plan from the Fairmount Park Conservancy—was supposed to benefit the economic outlook of the neighborhood and coalesce with other revitalization efforts in the community, such as the Hunting Park-based Esperanza’s affordable housing and education initiatives.

But economic development remains a work in progress. The latest estimates from the Census Bureau’s American Community Survey show that the average household income in Hunting Park is just under $24,000, which for a family of four is below the federal poverty line. In fact, average income has been dropping in recent years. When the pandemic struck, the neighborhood was one of the hardest hit in the whole city by cases of Covid-19.

One of the reasons given for Trump’s inroads in North Philly, cited by Black and Latinx voters themselves, was the first round of stimulus checks that went out to individuals this summer—emblazoned prominently (and controversially) with the president’s name. For some people in under-resourced neighborhoods, those checks felt like a rare moment of direct government action working in their favor.

Judging by the low turnout in Hunting Park, the checks didn’t inspire a huge amount of people to vote, but the idea remains an important one, because the link between voter participation and trust or satisfaction in government is foundational.

“You can’t go up to people who are barely surviving, barely living, and want them to participate in voting for the community,” says Graber. “What do people really get out of voting for these candidates?”

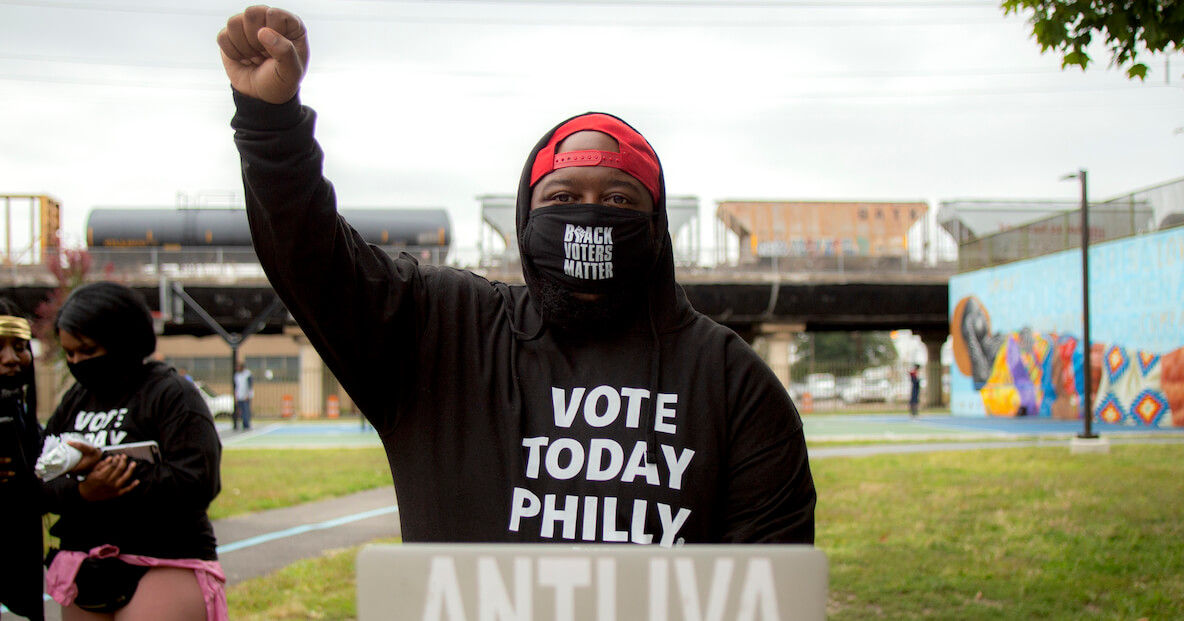

On weekends throughout the summer and fall, Graber spoke to eligible voters in Ward 7 at community events; she manned a table with free donuts and coffee, information on food banks, and voter registration forms. Graber witnessed a lack of belief in government’s ability to address the neighborhood’s pressing quality-of-life concerns.

“The biggest things that people talk about are the drugs, the trash, and the general situation around them for their kids,” she says. “Food insecurity is a big issue. A lot of people are living in multi-family housing. The opioid epidemic. These people often don’t have their basic needs met.”

Hunting Park voter turnout is typically low in presidential years, but it’s dismal in the years featuring mayoral or district attorney races at the top of the ballot, which is true of most of the city. Turnout dips dramatically across the city in municipal elections, which may be pointing to another problem.

“The primary reason we give [people] to vote is that local elections have a big impact on your daily lives and your neighborhood,” says Graber. “But I think people who’ve tried to access social services or resources often get denied help. That’s where a lot of disillusionment comes from.”

In the pursuit of spurring better turnout, what may be more important than federal checks is how residents interact with the day-to-day services of their government, if they have a relationship with them at all, and if they perceive them to be beneficial.

Myrna Pérez, a director of the Brennan Center’s voting rights and elections program, says that policies to improve access to the vote—same-day voter registration, automatic registration, and requirements for landlords to provide voting forms to all new renters (like this ordinance in St. Paul, Minnesota)—are essential to boosting turnout. But they’re not effective unless voters see the bedrock value of democratic participation.

“There is an anecdote in Philadelphia history that’s only partly true that poor areas don’t vote well,” says Jeffrey Carroll, a political scientist at Chestnut Hill College. “You actually have to distinguish between different places because all politics is local.”

“Can they imagine why voting makes a difference? The more we have to do to draw a clean link between voting and its effect, the harder it will be for people to turn out,” Perez says. “There’s a policy piece and an inspiration piece.”

There are researchers around the world who disagree about this correlation between voters’ dissatisfaction with government and low turnout. Some significant scholars argue that lower turnout is correlated with greater satisfaction, a sign of a content electorate. Other researchers endorse the idea that improving voters’ trust and satisfaction with democratic processes increases their likelihood to vote, and vice versa.

Interestingly, many studies argue that the experience of voting itself leads to more positive views of democracy—participation breeding more participation, a positive feedback loop over time. The more obstacles we take away in the voting process, then “the more likely it is that people will see its benefits,” Perez says. “The two speak to each other.”

However, unless an individual self-identifies as a voter, many GOTV strategies will remain ineffective. That’s consistent with the research of Dr. Melissa Michelson of Menlo College, whose expertise is in field experiments on voter turnout. Strategies like robo-calls, billboards, and commercial advertisements about elections—examples of the “noticeable reminder theory” in the GOTV lexicon—have demonstrated poor returns in many communities of color who have not traditionally voted.

“You can see that working for somebody who already has an identity as a voter and didn’t know that an election is coming up,” Michelson says of the noticeable reminder examples. “But for a lot of groups, like Latinx voters, there needs to be outreach through more personal contacts.”

One example of how to do that—albeit with a very different population—was the wildly successful GOTV strategy witnessed in Ward 21 this election cycle. Ward 21 covers parts of Roxborough and Manayunk, which are overwhelmingly white and where average household income is well greater than $70,000 a year, well above the city average. There, during the late summer and early fall, a group of civically active residents and committeepeople hand-wrote and hand-delivered more than 14,000 letters to people registered to vote but who hadn’t voted in the primary elections in early 2020.

“I remember when things were closing down, I started to think about the general [election] and voting by mail. I thought, wow, this is such an important election, so we have to start educating people how to vote from home now—and we can’t go door-to-door,” says Rebecca Poyourow, one of the committeepeople who spearheaded the effort and wrote an op-ed in the Inquirer detailing their efforts.

As the days counted down until Election Day, the group used an online database to figure out which voters hadn’t yet requested mail-in ballots and targeted those people for personalized follow-ups. “It’s not rocket science. It is persistence. It is using the data to see who has returned them, who hasn’t,” says Poyourow.

In the end, Ward 21’s turnout was 3,500 votes higher than in 2016, marking one of the largest gains across the city.

Although there’s no one-size-fits-all strategy for all neighborhoods, there is efficacy in having a trusted messenger doing the GOTV work, whether it’s a committeeperson or another neighbor. In an area like Hunting Park, research suggests that nonprofit providers—rather than members of a campaign or random volunteers—may be more effective at influencing turnout. According to a brief by the organization Nonprofit Vote, GOTV efforts conducted by nonprofits are much more likely to reach individuals—and be successful at turning them out—who are from racial minority groups and are lower-income.

“There’s not one theory to suit all communities,” says Michelson. “If you’re from a local community organization, you probably know them. You know if they really care about sick leave or gun control. They’re going to trust you more, because you’re telling them the truth.”

But outreach through a community nonprofit is exactly what Graber and others were doing in Hunting Park. “For all the efforts that we put in, the numbers went down,” she says. “People are still living through economic oppression.”

How to overcome the poverty hurdle

The correlation between low-resourced neighborhoods and low turnout has been explored many times over. Last August, the Poor People’s Campaign published a report titled, Unleashing the Power of Poor and Low-Income Americans, in which researchers estimated that 34 million poor or low-income Americans who were eligible did not vote.

Read the reportsDelve Deeper

But in the poorest big city in the country, there’s quite a bit of variance in voter turnout among high poverty communities. “There is an anecdote in Philadelphia history that’s only partly true that poor areas don’t vote well,” says Carroll. “You actually have to distinguish between different places because all politics is local.”

Carroll published a paper in 2018 titled Deep Poverty, High Turnout looking at Philadelphia’s relationship between voting behavior and concentrations of poverty. Unsurprisingly, he found that the neighborhoods with the worst states of poverty, including Ward 7, had the lowest turnout, and conversely, affluent parts of the city—the usual high-voting places like Ward 2 (Bella Vista), Ward 9 (Chestnut Hill), and Ward 10 (West Oak Lane)—performed the best.

Carroll suggests that the strength of turnout in West Philly is indicative of a culture of political inclusion that’s long in the making. It takes time to build, and might be in the early stages of establishing itself in a place like Hunting Park.

But after controlling for wealth, there were still anomalies across the city. “One can conclude from this study that many poor neighborhoods vote much better than expected given their poverty rates,” Carrol wrote in the paper. “West Philadelphia, highly afflicted with poverty, performs on pace with some of the more affluent areas of the city.”

In West Philadelphia, the cluster of wards 4, 6, and 44 stand out. Each of those wards has a high poverty rate of between 30 and 35 percent, yet they turned out to vote just below citywide averages in 2020, finishing with between 61 to 64 percent turnout. The situation in Ward 7 is more dire with a 50 percent poverty rate, but there’s a disproportionately large drop in turnout.

Carroll suggests that the strength of turnout in West Philly is indicative of a culture of political inclusion—a sort of critical mass of regular voters that’s been reached—that’s long in the making. It takes time to build, and might be in the early stages of establishing itself in a place like Hunting Park.

“In West Philadelphia, there’s a history of a stable African-American middle class and cohesive neighborhoods like Spruce Hill,” says Carroll. “All of that has been part of a rich culture and very robust shaping of political inclusion that’s been going on for decades.”

After mass white flight hit the area in the 1970s, a generation of Black politicians helped to ignite higher rates of civic participation in West Philly. They included Lucien E. Blackwell (City Council) and Hardy Williams (State Senate), who were eventually succeeded by Janie Blackwell (wife) and Anthony Hardy Williams (son).

The familiar names and faces of these political dynasties helped elevate and solidify the neighborhood ties to their democratic representation, the dividends of which continue to pay off today. They helped to ingrain the idea that government could and should be working toward the immediate needs of the community.

It may just be that Hunting Park is on a similar trajectory to parts of West Philly, only a generation behind as far as political inclusion, just now replicating the sort of candidates who can lead to better turnout by demonstrating a positive reciprocity between residents and elected representatives.

“Compare [West Philly] to what’s going on in the Seventh Ward and places that are in Councilwoman Maria Quiñones-Sánchez’s district, and you start to see that the political inclusion of those neighborhoods, particularly the Latinx, Hispanic, Dominican, Puerto Rican communities of Philadelphia, are just recently coming around in the last 10 years,” Carroll says.

Quiñones-Sánchez has held office since 2008, when she became the first Latina sworn into City Council and one of just a handful of Latinx politicians to be elected to any major office in Philly. During her decade-plus in office, the councilmember has focused on economic development and alleviating poverty in her district, the kind of issues that are topmost on the mind of Ward 7 voters.

“Sanchez,” Carroll wrote, “has led the charge in fostering legitimacy and accountability in her office for a constituency who may have lost faith in the effectiveness of local government.”

Whether that can translate into more votes in Hunting Park is still an open question. But it is maybe a step towards solving the chicken and egg riddle of what comes first—politicians who care about their constituents in poor and disconnected communities, or people in those communities electing politicians who care about them.

First, though, is the even harder challenge: Convincing voters why government matters in the first place.

This article is supported by the Solutions Journalism Network, a nonprofit dedicated to rigorous and compelling reporting about responses to social problems.

Photo by Phil Roeder / Flickr