Last week, when Philadelphia residents voted to effectively elect Cherelle Parker as our next mayor, more than seven in 10 registered Philadelphia voters were no-shows at the ballot box.

Despite an open seat race, high stakes and record-smashing spending, that’s pretty par for the course for a recent mayoral primary in Philadelphia, as it is for many big cities around the country in the elections that pick mayors. Here are a few things Philly might learn from places like Minneapolis, which saw more than half of registered voters cast a ballot in its last mayoral race, in 2021.

City residents energized

In 2021, Minneapolis voter turnout set a recent record, with 54 percent of registered city voters voting, compared to 43 percent in 2019 and 33 percent in 2013.

The 2020 murder of George Floyd in Minneapolis prompted discussions across the city about policing and the structure of Minneapolis’ government. A year later, these were major topics not only at the forefront of the 2021 mayor’s race, but also in a pair of questions directly on voters’ ballots: one on replacing the police department with a department of public safety, and another on the structure of the mayor-council relationship. There was also a 2021 ballot question about rent control.

Unlike ballot questions in Philadelphia, those in Minneapolis garnered a lot of attention and debate, huge sums of money on both sides — and lawn signs. That the questions considered race and policing tapped into the conversation locally and nationally.

Those factors likely played into high turnout in 2021, says Katie Smith, Minneapolis Director of Elections and Voter Services.

“We’ve had ballot questions that have gotten a lot of attention that have been on the same ballot as our mayoral races,” Smith says.

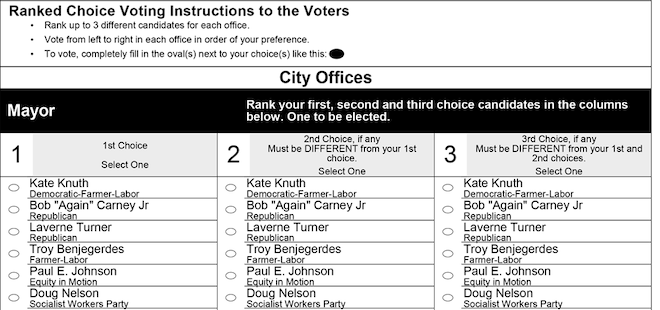

Minneapolis also has a lot of candidates working to get out the vote. Rather than a primary system like in Philadelphia, Minneapolis uses ranked-choice voting, which allows voters to choose among all the candidates, ranking preferences, on a single November ballot. In 2021, there were 19 people on Minneapolis’ mayoral ballot. The office is technically nonpartisan (though party affiliations are listed on the ballot), and candidates of every political stripe are on the same ballot.

“We have a lot of candidates that really, they’re out there, and they’re getting their population and their voters really excited. And they’re doing that work, as well, to encourage turnout,” Smith says.

To the extent that ranked-choice voting can increase turnout, it may be because it gives voters a greater sense of agency, an ability to vote for their first choice, even though they may not win, says Phil Keisling, a vote-by-mail advocate who previously served as the Oregon Secretary of State and studied mayoral turnout in cities around the country at Portland State University. That said, Keisling argues that ranked choice alone doesn’t make up for a lack of electorate-animating issues or people who think the election matters.

Another turnout advantage to Minneapolis’ elections may be its timing. The election is held in November — not in May, like Philadelphia’s deciding election, when voters’ minds might be more preoccupied with summer vacation plans.

State factors, including a culture of voting and easy ballot access

Minnesotans like to believe that a culture of civic engagement is responsible for the state’s high voter turnout: True, Minnesotans volunteer at higher-than-average rates and tend to have at least a modicum of trust in government. Those factors are oft-cited as reasons Minnesota usually ranks among the top, if not No. 1, when it comes to statewide turnout in midterm and presidential elections.

Does that trickle down into local elections?

Smith says she thinks it helps. “Between our statewide turnout, our county turnout, our local and municipal turnout, we really have a voting population here. We have people that are engaged, that enjoy participating,” she says.

Others cite structural considerations — like ease of voting — to explain Minnesota’s generally high turnout. Whereas in Pennsylvania, voters must register at least 15 days in advance of the election, voters in Minnesota can register at the polls on Election Day, something research has found improves turnout, particularly among young voters, as well as Black and Latino voters.

In partisan elections, it’s also generally easier to access primary ballots in Minnesota than in Pennsylvania. Minnesota is an open primary state. That means any registered voter can vote in any party’s primary — without ever registering with a party.

In Pennsylvania, by contrast, voting in a party primary can take considerable forethought. Voters must register with the party whose primary they want to vote in before Election Day in order to vote for mayor. Rules like this discourage many voters — in particular, the young, who are disinclined to join parties in the first place, says Keisling. Closed primaries can also discourage voters who aren’t affiliated with the major party in power, in Philadelphia’s case, Democrats.

Structural factors affect turnout

Making voting easy is critical to increasing turnout, Keisling says, citing Pew research that found in 2016, nearly half of registered voters didn’t vote because of logistical issues.

It’s for those reasons and others advocates propose all vote-by-mail elections (and moving municipal elections to even years to coincide with higher-turnout midterms or presidential elections), among other reforms, to turn out more voters in U.S. cities.

Another obstacle big cities face in increasing voter turnout is the lack of discussion, when turnout is low, about why that is and what could fix it, Keisling says. Least of all, among politicians.

“If I have to run a campaign across the city, and I’ve got to raise a bunch of money, and I’ve got to go out and meet a lot of voters,” Keisling says. “It makes their job easier when turnout is smaller.”

![]() MORE ON ELECTIONS FROM THE CITIZEN

MORE ON ELECTIONS FROM THE CITIZEN