![]() A few weeks ago, New York magazine ran a cover story headlined “How The Mayor Lost The City,” a devastating account of the fall of Bill de Blasio. Writer David Freelander paints a portrait of a suddenly dystopian Gotham, whose chief executive, in a time of crisis, dithers and seems to fall deeper into isolation and failure.

A few weeks ago, New York magazine ran a cover story headlined “How The Mayor Lost The City,” a devastating account of the fall of Bill de Blasio. Writer David Freelander paints a portrait of a suddenly dystopian Gotham, whose chief executive, in a time of crisis, dithers and seems to fall deeper into isolation and failure.

Not long ago New York was the safest big city in America, a stunning turnaround under Mayors Giuliani and Bloomberg, but now murders are up by 25 percent; one recent week saw 63 shootings, compared to 26 the same week just a year prior. In June, shootings hit the highest monthly total in 25 years, while the Fourth of July weekend brought several dozen more, plus nearly a dozen homicides.

Retailers have proclaimed the Big Apple the “worst city to do business in” in the age of Covid; even before the pandemic, trash collection in de Blasio’s metropolis had earned it the nickname, “The city that never sweeps.”

After reading the NY Mag piece a second time—astoundingly, former high-level staffers of de Blasio’s are, on-the-record, leading protests against him outside Gracie Mansion—it dawned on me that, when Freelander diagnoses the character traits and missteps that have led to de Blasio’s fall from grace, you could just as easily substitute the name “Kenney” for the New York mayor’s. Because leadership often fails in strikingly similar ways.

What emerges in Freelander’s portrait of de Blasio is a detached, insecure leader who doesn’t consult a wide array of voices. “He doesn’t listen to a lot of people,” says one staffer. Freelander writes:

The mayor is seldom out among everyday New Yorkers. He kept up his routine at the Park Slope Y in the face of widespread mockery all these years because he said it connected him to his previous, pre-mayoral self, but while there, he rarely talked with his fellow gym-goers. Eagle-eyed Brooklynites have snapped pictures of the mayor walking in Prospect Park, catching him and [wife Chirlane] McCray huddled against each other and glowering at anyone who bothers to interrupt their tete-a-tete.

Five years ago, candidate Jim Kenney seemed to model his campaign on the same progressive tenets that de Blasio used to capture City Hall. Turns out, the two have more in common than political rhetoric.

I’ve written often about the insularity of Kenney’s team; on critical strategic matters, it’s often a closed white guy brigade—many of whom live near one another and some of whom actually grew up together—consisting of soon-to-step-down Managing Director Brian Abernathy, Chief of Staff Jim Engler, Finance Director Rob Dubow and Deputy Mayor of Labor Rich Lazer.

“I’ve never interacted with a politician less willing to reach out and listen than Jim Kenney,” one prominent civic and business leader told me this week, shaking his head in resignation.

If you’re not governing, as certain mayors and an Impostor-in-Chief just might prove, eventually there will be no one to blame anymore. At some point, there is nothing left to spin.

Like de Blasio, Kenney often seems irritated, or downright depressed. One night, having drinks alone at a bar, he marched my sister and her boyfriend through a litany of complaints detailing why he hates his job. (“I guess you can’t pick your family,” he said when she told him I was her brother.) She couldn’t wait till her table was ready, because he was bringing her down. This was pre-pandemic, mind you; just imagine how miserable the poor guy is now that the job is so much harder.

Thing is, you don’t need an overabundance of vision or enthusiasm to be a successful mayor. Competence will often do. Late Boston Mayor Tom Menino never made a chill run up anybody’s leg—his nickname among the press was “Mumbles” and he once famously observed, “I have did my duty”—but he got his city. He once observed that the best thing about being mayor was that “I get to be everybody’s neighbor” and, man, was he proficient at delivering city services to them.

Menino proved that it doesn’t take much to satisfy a local electorate. The average taxpayer wants to know that when she calls 911, police or fire or EMT will show up; when it snows, the streets will be cleared, and that, when she places her trash on the curb, it will be picked up once a week. That’s the non-negotiable baseline for governance.

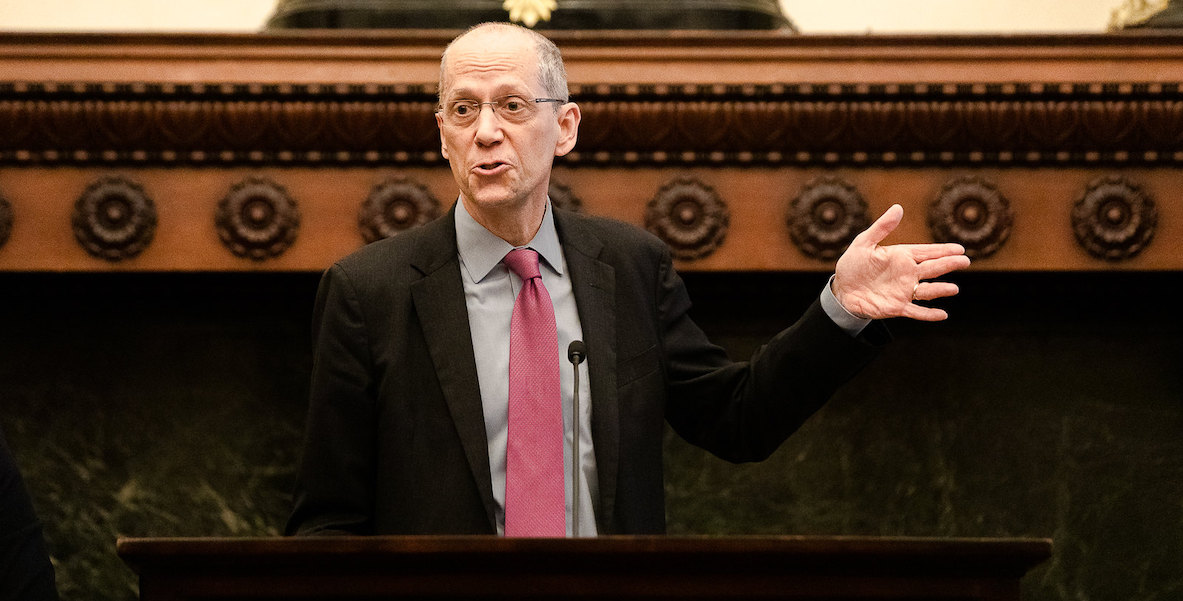

![]() The problem for both de Blasio and Kenney is that they’re neither visionary or competent at making government work for real people. Earlier this week, as part of our virtual town hall series, I interviewed the millennial mayor of Birmingham, Alabama, Randall Woodfin, who is both a visionary and technocrat. He was endorsed in 2017 by Bernie Sanders, has endorsed Joe Biden this time around, and marries progressive policies with pragmatic politics in order to get stuff done for his constituents.

The problem for both de Blasio and Kenney is that they’re neither visionary or competent at making government work for real people. Earlier this week, as part of our virtual town hall series, I interviewed the millennial mayor of Birmingham, Alabama, Randall Woodfin, who is both a visionary and technocrat. He was endorsed in 2017 by Bernie Sanders, has endorsed Joe Biden this time around, and marries progressive policies with pragmatic politics in order to get stuff done for his constituents.

“The number-one job of any mayor in America is public safety,” Woodfin says. “Every decision we make in the public safety realm has to be measured and balanced; it can’t be knee-jerk, it can’t be reactionary.”

That’s why he’s reformed policing—the outright banning of chokeholds, for instance, and the adoption of a “duty to intervene” policy—while at the same time adding (well-trained) cops to the force. Because enlightened leadership sees beyond the shibboleths of ideological talking points.

Contrast that to Kenney and de Blasio, both of whom oversee police forces that have run amok—Kenney initially defended using tear gas on peaceful protestors and de Blasio defended cops running them down with SUVs—and that fail to reverse horrific crime trends.

You can’t make this up: Both pander to the political left, both turn a blind eye to solving crime, and both, fearful perhaps of police union backlash, tolerate over-policing. (This is why the issue of police reform is so thorny, as made clear in Jill Leovy’s terrific 2015 book, Ghettoside: A True Story of Murder in America: Cops are often both occupying inner-city para-military force and incompetent when it comes to actually solving murders that disproportionately kill African Americans.)

Neither Kenney nor de Blasio seem capable of, or interested in, meeting Woodfin’s test of delivering on public safety. De Blasio has passed the buck by shrugging off a historic gun violence spree in his city as the natural result of “cabin fever” caused by the coronavirus lockdown, and Kenney had his new police commissioner release a not-so-inspiring policing plan that—I kid you not—you have to work hard to even find online. In a deliciously symbolic twist, it’s easier to find a press release about Danielle Outlaw’s Crime Prevention & Violence Reduction Action Plan than it is to actually find the plan.

The problem for both de Blasio and Kenney is that they’re neither visionary or competent at making government work for real people.

Like de Blasio, Kenney often implies, or flatly states, that the buck stops elsewhere. His jettisoning of Abernathy, like the pressure he applied for the resignation of Free Library Director Siobhan Reardon, weren’t examples of mayoral problem-solving or of holding others accountable, so much as lazy scapegoating.

I’ve written in the past about the administration’s allergy to accountability, as when Chief of Staff Jim Engler once said “No, that’s not how we operate” when asked if anyone would be fired back when the city couldn’t find some $33 million of your taxpayer dollars in its own, un-reconciled bank accounts. Remember that example of your government at work for you?

Well, fast-forward to last week, when trash was piling up on city streets, the stench wafting through the air. Kenney dispatched Carlton Williams, his Streets Department commissioner, to pen an excuse-laden op-ed in the Inquirer attempting to explain why the City has been so derelict in picking up residents’ trash: Workforce shortages due to Covid-19. More trash due to more waste generated in homes. Personnel working overtime to clean up after protests. Severe weather producing torrential rains and flooding.

![]() Nary a solution or plan offered. “Imagine Jeff Bezos sending this memo to explain why Amazon is not delivering packages,” one local business and civic leader emailed upon reading it. The mayor could have said, “We’re not going to tolerate trash strewn throughout our streets,” and he could have made a one-time transfer of his treasured soda tax funds to hire extra sanitation workers—maybe even going so far as to deputize a $15-per-hour army of those who have been laid off during the pandemic to gather in common cause and clean up our city.

Nary a solution or plan offered. “Imagine Jeff Bezos sending this memo to explain why Amazon is not delivering packages,” one local business and civic leader emailed upon reading it. The mayor could have said, “We’re not going to tolerate trash strewn throughout our streets,” and he could have made a one-time transfer of his treasured soda tax funds to hire extra sanitation workers—maybe even going so far as to deputize a $15-per-hour army of those who have been laid off during the pandemic to gather in common cause and clean up our city.

That would be visionary, and inspiring, and practical. It’s the type of thing you can imagine seeing from a Lori Lightfoot in Chicago or a Randall Woodfin. But in Philadelphia, with our worst in the nation poverty, with our explosion of murders and shootings, with our burdensome tax rate, few things seem to be seen as a crisis at City Hall.

To be fair, the Kenney administration—like the state of Pennsylvania—has seemed to manage the pandemic quite well. (Though early on, Kenney—again like de Blasio—resisted state efforts to lock down, actually urging folks to go out to restaurants and tip their waitstaff.) But you don’t get a pass when it comes to things that are the bedrock foundations of the chief executive’s job in a city, things like keeping residents safe, picking up the trash and being a trusted steward of taxpayer dollars. (According to Councilman Allan Domb, the city’s Five-Year Plan contains a troubling $126-million discrepancy.)

Both Kenney and de Blasio have been loud, sneering critics of Donald Trump, and both are blind to just how much they’re mirror images of him.

For all the energy both Kenney and de Blasio have expended courting Democratic Socialists, for all the slogans and soundbites—Kenney’s vilification of Hahnemann owner Joel Freedman took a page right out of de Blasio’s playbook—their mayoralties are both turning out to prove that there’s no way to spin leadership in cities. You either deliver for your people, or not.

Ironically, the same notion just might apply to the presidency.

Both Kenney and de Blasio have been loud, sneering critics of Donald Trump, and both are blind to just how much they’re mirror images of him. Both attack critics rather than engage their criticism; both pander to their base at the expense of providing for the general welfare; both have been revealed as incompetent managers of the machinery that is government. Like Trump, they’re little more than glorified pundits in positions that demand the hard work of political blocking and tackling.

![]() On the national level, there are few episodes that illustrate a failure of governance more strongly than a pandemic that, after five months, finds a chief executive grudgingly talking about putting a plan together, as Trump did this week. And, locally, there are few examples that tell a story of failure more strongly than when murders reach epidemic levels and trash doesn’t get picked up.

On the national level, there are few episodes that illustrate a failure of governance more strongly than a pandemic that, after five months, finds a chief executive grudgingly talking about putting a plan together, as Trump did this week. And, locally, there are few examples that tell a story of failure more strongly than when murders reach epidemic levels and trash doesn’t get picked up.

Who would have thunk that, in the year 2020, Jim Kenney, Bill de Blasio and Donald Trump might all be revealed?

This is a good thing. After hearing from Woodfin, I actually found myself feeling optimistic. Someone is governing somewhere; maybe the discreet skill set of politics—aligning values and goals, building coalitions in pursuit of the common good, using government to serve—isn’t as dead as may appear.

Because the object lesson is now clear. If you’re not doing that, if you’re not governing, as certain mayors and an impostor-in-chief just might prove, eventually there will be no one to blame anymore. At some point, there is nothing left to spin.

Photo by Albert Lee / City of Philadelphia