It was a rainy November day during Thanksgiving weekend of 1997. The scene was the Washington, D.C., childhood home of Dr. Evelyn Brooks Higginbotham, A. Leon Higginbotham Jr. beloved wife. Our assignment was to assist in the removal, packing, and transport of a few prized family heirlooms that were to be taken to their home in Newton, Massachusetts.

On the early morning drive into Washington, D.C., our conversation was mostly idle chit-chat. Little did we know that the circumstances of the day would lead to an amazing set of discussions, the importance of which we could never have imagined at the time. When we arrived, we were greeted by the Judge, who had just finished his breakfast. As we entered, he smiled and gave a sigh of relief, noting that we had just enough time to pack up the items, load the car, and safely get to the airport even in the midst of the heavy rainfall.

“Old soldiers do die”

The Judge was pleasant but deliberate as he began discussing our task. During the course of the Judge’s instructions, perhaps as a way of encouraging the swift completion of our duties, he proudly shared that his wife was quite a track star in high school. He explained that she was known not only for her sheer speed, but also for the precision of her passage of the baton during relay races.

As the rain intensified and delay seemed inevitable, the Judge made a decision to take a later flight. Now visibly more relaxed, he began to reflect on his life and the current state of race relations. Perhaps still thinking about his wife’s track and field exploits, he wondered out loud, “Who would carry the baton in the new millennium?” This time, however, the race to which he was referring was not on the field of athletic competition, but involved the comprehensive national civil rights agenda that began in the early 1960s.

“If our voices fade to silence it will be extremely difficult to revive them” the Judge explained. “One by one, our traditional civil rights issues will drop from both local and national radar screens. Such a development would be a real American tragedy.”

The conversation started with the frightening reality that old soldiers do die. The Judge queried, “Do you realize that within five years, we of the civil rights old guard are all going to be dead or near dead?” He talked of his concern about the stagnation of the civil rights movement and how committed advocates seemed to be overburdened with the multitude of issues and distractions presented by current events.

It is not that the Judge believed other social issues were not important; rather, his concern was that support for civil rights in general was fading and too little progress had been made since the early 1960s when he began his career in public service.

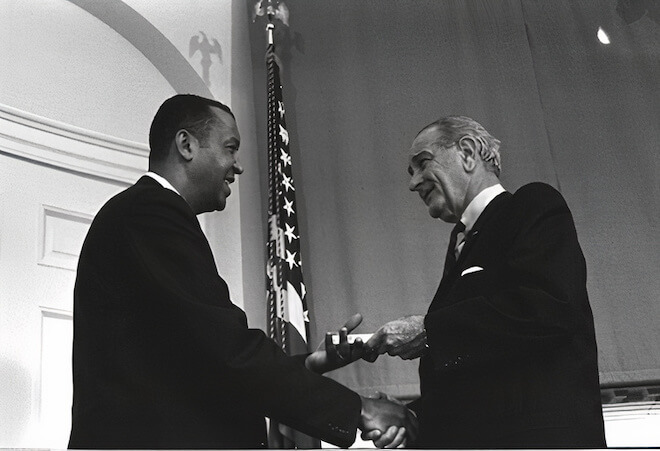

By appointment of President Lyndon B. Johnson, Judge Higginbotham served as vice chairman of the National Commission on the Causes and Prevention of Violence. Chief Justices Warren, Burger, and Rehnquist appointed him to a variety of Judicial Conference committees and other related responsibilities. Prior to his judicial appointment, he served as President of the Philadelphia Branch of the NAACP, as a commission of the Pennsylvania Human Relations Commission, and as a special deputy attorney general. In November 1995, he was appointed to the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights. He reminded us that those forces who would dismantle all that had been built by the civil rights old guard were busy at work with their destructive philosophy.

Mass media failed civil rights

The Judge observed that those persons who were willing to speak against traditional civil rights positions like integrated public education, affirmative action, and public assistance for the poor, could always find access to the mass television and print media in order to make their misguided points. This was particularly true for minorities who would speak against these traditional positions.

The average citizen who has time only for the evening news and mainstream newspaper sees these frequent commentaries and tends to believe that there is much more disunity within the civil rights community and less consensus among its leaders than really exist.

Another problem with the anti-civil rights commentary in the mass media is the lack of opportunity to refute it. There are relatively few commentary pieces by racial minorities in the opinion and editorial pages of major newspapers. The Judge believed that the role of the scholar publishing articles in journals, newspapers, and magazines was important and should be continued. He believed, however, that there was an immediate need to add new names and fresh perspectives to the frequent voices in the nation’s commentary pages.

The Judge suggested that major newspapers and television networks get comfortable with the few well-established civil rights commentators like Carl Rowan, Clarence Page, and Anthony Lewis. He reasoned that while these commentators have made significant contributions, other perspectives could add to the valuable dialogue.

In addition, he spoke glowingly of the inroads that members of the Harvard African-American Studies Department were making to bring a greater legitimacy and larger audience to the sophisticated study of racial issues. Led by Henry Louis Gates Jr., and housing such luminaries as Cornel West, William Julius Wilson, and Evelyn Brooks Higginbotham, the Judge believed that major strides could be made because of the power and heightened visibility provided by Harvard’s position in the intellectual community.

Still, the Judge noted that no matter how visible the national commentators might get or how illustrious Harvard and its faculty might be, these scholars were only a handful, and Harvard was but one place with a finite number of people. He lamented that such a group could only do so much while reminding us that there were thousands of newspapers, magazines, and television and radio stations affecting the attitude of millions of Americans everyday.

The Judge reasoned that what was required to make a real impact was the constant push to be heard by an ever-increasing number of voices. He explained that although the number of racial minorities in the academic community was still sorely under-represented both at the college and law school levels, there were still outstanding scholars of color in every part of the country teaching at schools of every size and type. These less-known scholars have produced outstanding work but have not gotten adequate exposure. The Judge believed these thinkers were the key to keeping the civil rights agenda squarely before the public.

He envisioned that they needed to be vociferous and constant voices in their respective comers of the world, constantly pushing to make their positions known to the local media, even if their attempts were frequently rejected.

This squeaky wheel gets the grease theory was not simply a suggested approach but an imperative survival technique. The Judge explained that “if our voices fade to silence it will be extremely difficult to revive them. One by one, our traditional civil rights issues will drop from both local and national radar screens. Such a development would be a real American tragedy.”

A chronicler of race and discrimination

Much of the Judge’s scholarship focused on the real American tragedy of racial discrimination. In his 1978 masterpiece, In the Matter of Color, he provided a penetrating account of the racial discrimination that existed when the Constitution was created.This work was rich in historical detail and in the analysis of cases and statutes. What set In the Matter of Color apart from other historical works on race was its detailed statute and case law discussion.

While the Judge explained that his first book brought a great deal of attention to the issues that he believed were important and did so in a way that law review articles could not, he warned that writing comprehensive books was very time-consuming, requiring long periods of uninterrupted concentration that he rarely enjoyed with his busy schedule. It was this schedule, he explained, that had delayed the publication of his most recent book, Shades of Freedom: Racial Politics and Presumptions of the American Legal Process.

Shades of Freedom documented how United States law was used to create and embrace notions of racial inferiority. Using concrete statistics and penetrating news accounts, Shades of Freedom strikes at the core of the current debate over whether racism is a thing of the past or continues to thrive by demonstrating that the more things change, the more they stay the same.

For those who are uncomfortable with candid racial dialogue stated in direct terms, Shades of Freedom will be an unsettling read. Even from its opening passages, the Judge confronts the painful legal history of racism in America. He writes that insofar as the law was concerned, “Negroes were not differentiated from ‘sheep, horses, cattle,’ or ‘mares.’”

The book describes how the legal system prevented the progress of racial minorities because of the law’s embrace of presumptions of racial inferiority. According to the Judge, “The dominant perspective within this volume is the role of the American legal process in substantiating, perpetuating, and legitimizing the precept of inferiority,” Shades of Freedom challenges its readers not to ignore the realities of the historical and statistical perspective. It provides a refreshing change from vague generalities about racial issues that have characterized other recent works attempting to survey the racial landscape.

For those who are uncomfortable with candid racial dialogue stated in direct terms, Shades of Freedom will be an unsettling read. Even from its opening passages, the Judge confronts the painful legal history of racism in America. He writes that insofar as the law was concerned, “Negroes were not differentiated from ‘sheep, horses, cattle,’ or ‘mares.’”

For those who are uncomfortable with candid racial dialogue stated in direct terms, Shades of Freedom will be an unsettling read. Even from its opening passages, the Judge confronts the painful legal history of racism in America. He writes that insofar as the law was concerned, “Negroes were not differentiated from ‘sheep, horses, cattle,’ or ‘mares.’”

The book describes how the legal system prevented the progress of racial minorities because of the law’s embrace of presumptions of racial inferiority. According to the Judge, “The dominant perspective within this volume is the role of the American legal process in substantiating, perpetuating, and legitimizing the precept of inferiority,” Shades of Freedom challenges its readers not to ignore the realities of the historical and statistical perspective. It provides a refreshing change from vague generalities about racial issues that have characterized other recent works attempting to survey the racial landscape.

“The precept of inferiority”

The book begins with the clever device of listing several notorious examples of recent situations where Blacks were wrongly accused of perpetrating heinous crimes. The examples were characterized by two interesting features. First, they came to the attention of most Americans through the mass media. Second, each involved White people accusing an anonymous and nonexistent Black person of committing the crime.

Particularly noteworthy among the examples was the 1994 accusation of Susan Smith, who claimed that an “armed Black man perpetrated a car-jacking, kidnapped her children who were in the vehicle, and left her [injured] on the side of the road.” It was later discovered, after weeks of network news coverage regarding the abduction and the search for the alleged Black perpetrator, that the story was a total fabrication. Smith was later arrested, tried, and convicted of the murder of her own children.

Another shocking example offered by the Judge was the 1990 case of Charles Stuart, who claimed his pregnant wife had been assaulted in her vehicle and killed by a Black man attempting to steal her cash and jewelry. In fact, Mr. Stuart was the prime suspect in the killing of Mrs. Stuart, who died from a gunshot wound to the abdomen, in an elaborate scheme devised by Mr. Stuart and his brother to collect life insurance benefits.

The Judge found that these examples of false accusation confirmed “the centuries-old precept of inferiority.” As a result of this finding, he reasoned that “[t]he perception of inferiority that motivated these false accusations against Blacks in the 1990s is not unrelated to the perception that legitimized slavery.”

Legalized, institutionalized inequity

The Judge concluded that the use of race in these cases was neither incidental nor accidental He supported his conclusion with a cogent statistical analysis quantifying the present inequality suffered by Blacks as compared to their White counterparts. He noted:

In 1993, 28.9 percent of African-American households earned under $10,000 per year, while 12.2 percent of White households earned under $10,000 annually. Disparities are, perhaps, the most striking when we witness the plight of America’s children. In 1989, almost half (46.1 percent) of all African-American children lived in poverty, compared with 17.8 percent of White children. In 1993, in contrast, 1.9 percent of African-American households earned over $100,000 annually, as did 6.3 percent of White households.

The Judge argued that these economic differences were merely a result of continuing racial discrimination, a discrimination that manifested itself in different forms but nevertheless was based on the same underlying assumptions. He called his principal theory the “Ten Precepts of American Slavery Jurisprudence.” He asserted that these precepts “represent the institutionalized values, standards, or assumptions for which there was a broad acceptance, at least on the part of those who wrote and interpreted the laws.”

The Judge did not waiver on his position that the precepts were embraced by American law. For example, in discussing the “precept of inferiority,” he reminded readers of the fateful words of Chief Justice Roger Brooke Taney‘s opinion in Dred Scott v. Sanford, where he reasoned that Blacks, “being[] of an inferior order, and altogether unfit to associate with the White race … and so far inferior, that they had no rights which the White man was bound to respect; and that the negro might justly and lawfully be reduced to slavery for his [own] benefit.”

The Dred Scott opinion will be remembered as the legal decision that paved the way for the Civil War. It will also be remembered, however, as the case that most clearly demonstrates that many White Americans embraced the notion of Black inferiority.

Justice Taney explained that the assumed inferiority of Blacks at the time the country was founded was “fixed and universal in the civilized portion of the White race. It was regarded as an axiom in morals as well as in politics, which no one thought of disputing, or supposed to be open to dispute.” This view was shared by other writers of the time and endured after the Civil War into the early 1900s.

The Judge suggested that the belief that “Blacks are of an ‘inferior order’ is an idea that some find difficult to abandon.” Although he recognized that many people would challenge this precept and even more would find the suggestion that they harbor such feelings “downright insulting,” he pressed the point in order to attack the notion that the Civil War had a cleansing effect on the sin of slavery. He expressed grave concerns about the assumption held by many Whites that there is no race problem at all that involves their participation.

He concluded that the majority of White Americans believe “that they personally have nothing whatever to do with slavery, segregation, or racial oppression because neither they nor as far as they know — their ancestors ever enslaved anyone, ever burned a cross in the night in front of anyone’s house, or ever denied anyone a seat at the front of the bus.” This “self absolving denial,” he maintained, made it “nearly impossible to have an honest discussion about what used to be called ‘the Negro Problem.’”

It goes way beyond the legal system

It is at this stage in Shades of Freedom that the Judge made his most powerful points. Although he identified the legal system as the primary culprit in the historical enforcement of the principle of inferiority, he noted that the legal system did not create the inferiority that it supported. He explained that “[from the time the Africans first disembarked here in America, the colonists [presumably without the benefit of any law] were prepared to regard them as inferior.” Thus, “when the law abolished state-enforced racial segregation, it still did not eliminate the precept [of inferiority].”

This explains why it is so difficult to remove racial oppression from our society even though dejure segregation and discrimination have been eliminated in the law. The Judge believed that the reason why so many statistical, economic, and educational disparities are attributed to racism by most Blacks and dismissed as mere coincidence by many Whites is because the effects of dormant or even unconscious racism emerge through the application of law, but can not be directly traced to the law itself.

Jeffrey Rosen, [National Constitution Center president and CEO], writing in late 1996 for The New Republic, characterized the historical arguments made in Shades of Freedom as “crude.” Rosen maintained that the Judge was “wrong to believe that the racism of the Reconstruction Republicans was formally enshrined in the American Constitution” and “that most Whites in the Reconstruction era were unwilling to live alongside African-Americans as equal citizens.

The history the book identifies, however, is the best response to Rosen’s critique. If the Constitution and the states had adequately protected Blacks, why has history demonstrated so strongly their need for legal protection? If Whites were so willing to have Blacks live side by side with them after Reconstruction, why was the legislative and judicial movement advancing segregation so widespread, and why were so many Whites resistant to integration?

While no stranger to criticism from conservatives and never hesitant to refute their constant attacks, the Judge’s primary concern was to continue the progress begun by the civil rights movement. He recognized that the civil rights tradition that he was fighting to preserve was much more important than his own popularity. Personal attacks, no matter how unfounded, would not dissuade him from this focus.

The Judge expressed specific concerns about several recent decisions of federal circuit courts of appeals that attacked traditional civil rights doctrine. He spoke of the Fifth Circuit’s affirmative action decisions and the Fourth Circuit’s approaches to accused criminals’ procedural rights that represented what he called a “substantial threat to what I thought was well settled legal doctrine.”

The Judge suggested that some legal scholars needed to get together and “do the difficult work of reviewing every reported civil rights decision of the Circuit Courts and attack those decisions which would serve as precedent to turn back the civil rights clock.” He lamented that he did not have time to do it himself, saying that such an effort done properly would require thousands of hours by many diligent academics. He considered such an effort, however, to be the single most important scholarly project one could imagine.

As the rain began to subside and the sun peeked through the clouds, the Judge concluded the conversations of the day with the hope that sometime soon he could sponsor a conference in order to discuss some of these ideas with the many supporters of civil rights throughout the country. He thought that such a gathering could be the touchstone for new strategies and initiatives to create equal opportunity in the new millennium. He imagined a conference similar to the legendary Niagara Movement, which served as a catalyst for the important work of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People.

As he finished loading the car, the Judge’s final thought of the day was about the importance of helping others. He said that minority academics must be mindful of those coming along and should provide them an opportunity to participate in ventures that give them a voice. The Judge was well known for traveling with a host of mentees, assistants, and law clerks, demonstrating the power of his life through example rather than mere talk. He made it clear that to help others was not merely an opportunity, it was a responsibility.

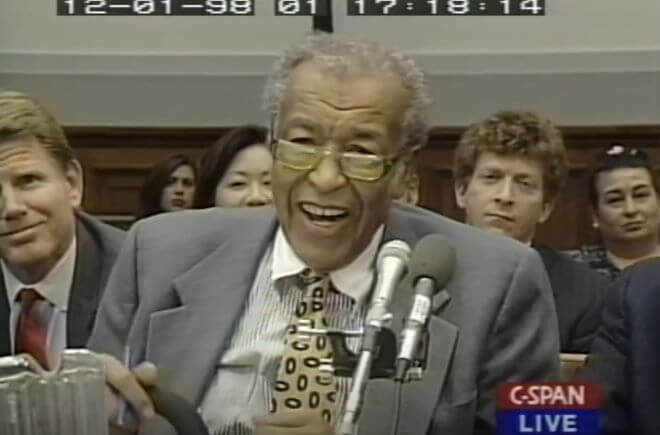

The Judge’s final testimony

On December 3, 1998, the Judge made his last public appearance, testifying before the House Judiciary Committee considering the impeachment of President William Jefferson Clinton. His powerful and scholarly testimony before the committee helped to convince many members of Congress that the impeachment of Clinton was unsupported by Constitutional provisions, inconsistent with legal history, and politically divisive.

As the testimony concluded, the C-SPAN programming continued to show the hearing room as telephone callers made comments about the proceedings. The silent pictures of the hearing room spoke volumes about the Judge’s character. While the program host entertained callers, the picture in the hearing room showed a number of Congresspersons and staffers requesting photographs with the Judge, to which he happily obliged. With his broad smile and while leaning on the long cane that he used to assist in his travel since undergoing three life-threatening operations just two years earlier, the Judge chatted attentively with his admirers, treating each as if he were greeting an old friend.

As he demonstrated one last time during the impeachment proceeding, as he had done so many times throughout his professional career, the Judge carried the civil rights baton, constantly advancing it forward and carefully protecting it for the next carriers. His message was always put in the most positive light, “While much had been accomplished, even more remained to be done.” While the race for equal justice continues, the Judge has finished his portion of the event. But as we remember his life and celebrate his accomplishments, we must not forget his most important question: “Who will carry the baton?”

This piece originally ran in the April 2000 issue of Loyola of Los Angeles Law Review.

![]() RELATED

RELATED