Like parents across the country, Philadelphian Mike Lahiff knows what it feels like to worry about the toll frequent mass shootings and active shooter drills take on children.

Shortly after the Stoneman Douglas High School shooting in Parkland, Florida, in 2018, his daughter’s junior high school started conducting active shooter drills. She would come home distressed, leaving Lahiff frustrated because he didn’t know how to help her feel safe in school.

“It feels like every time you turn on the news, you just see another school shooting,” Lahiff says. “I was like, something needs to happen.”

Recording shootings in the U.S.

Last year, the Gun Violence Archive, a nonprofit that tracks gun violence, counted 647 mass shootings and 20,190 homicides in the United States. Education Week reports that there were 51 school shootings last year. Some schools — including Philly’s high schools and middle schools — have installed metal detectors and conduct weapons screenings to ensure students aren’t bringing in firearms. Nationwide so far this year, though, there have already been 33 mass shootings across the country.

As Lahiff waited after school one day to pick his daughter up from sports practice, he noticed that her junior high was filled with security cameras. But when he asked a school official how the cameras were being used to protect students’ safety, he was told that no one monitors them. They only check the footage after incidents occur.

“I was like, Wait a second: Why don’t we use them to detect guns? If people could do facial recognition technology through security cameras, why can’t we focus on detecting guns?” he recalls thinking.

Lahiff, a former Navy SEAL who attended The Wharton School of Business, had dabbled in tech startups and previously worked for Comcast as director of digital programs. With his military experience and tech background, he thought he could be the person to create such software. So he assembled a team and founded ZeroEyes, a Conshohocken-based security software company that uses artificial intelligence to detect firearms in live security camera feeds and dispatch authorities.

By installing ZeroEyes software in cameras in high-traffic areas on the city’s subway stations, SEPTA is hoping to maximize the technology it already has in place to detect incidents and quickly deploy police to those locations.

Since launching in 2019, ZeroEyes has garnered over 100 clients in 30 states and three countries. Next month, they’re partnering with SEPTA to install their software in 300 of the transit system’s more than 30,000 cameras.

SEALs software startup

Once Lahiff got the idea for ZeroEyes, he called his friend Sam Alaimo. The pair met in the early 2000s when they were both Navy SEALs. Lahiff had dropped out of college to enlist shortly after 9/11. Alaimo joined the Navy in 2009 after dreaming of becoming a SEAL since he was 14 years old. Both served until 2013. When Lahiff called him, Alaimo was working in private equity and trying to find a job with more purpose.

“I was basically like, Hey man, how do you feel about doing something to stop school shootings?” Lahiff says. “And Sam was like, Fuck yeah.”

Together, they rounded up a team of former SEALs and military veterans, many with backgrounds in finance and tech, to be ZeroEyes founders. They included Rob Huberty, co-founder and chief operations officer, who’d worked for Amazon after retiring from the SEALs, and Dustin Brooks, chief customer officer and also a co-founder. Both also worked with Lahiff when he first got out of the Navy.

The group worked together on creating software that could recognize firearms out of Lahiff’s basement. They scraped the internet for images of guns to use as a database so that artificial intelligence can learn and detect what different types of guns look like. Then, they started testing the software on movies to see if it could recognize firearms.

“It was detecting guns in The Matrix. We thought, oh, this is sweet,” Lahiff says.

The next step was seeing if it could detect firearms in security camera footage. They set up cameras outside Lahiff’s house and walked around outside carrying guns. The system kept going off, but this time, it was picking up everything but the firearms.

Part of the issue with the software was that the data they’d scraped from the internet didn’t reflect how guns might look in real-life scenarios. The pictures were well-lit, clearly visible, and close to the camera — basically how guns look in movies. But in real life, when someone might be trying to conceal a weapon, they may walk through areas of low light or far from cameras.

“It worked horribly,” Lahiff says. “We realized we have to create our own data and be very meticulous about it.”

So the team started filming themselves walking around carrying different types of different guns in different environments. They considered factors like lighting and distance from the camera. The owners of a waterpark in Delaware that was closed for the winters allowed them to string up cameras and film themselves walking around with firearms so that they could collect more data.

The new scenario worked.

Firearm detection goes live

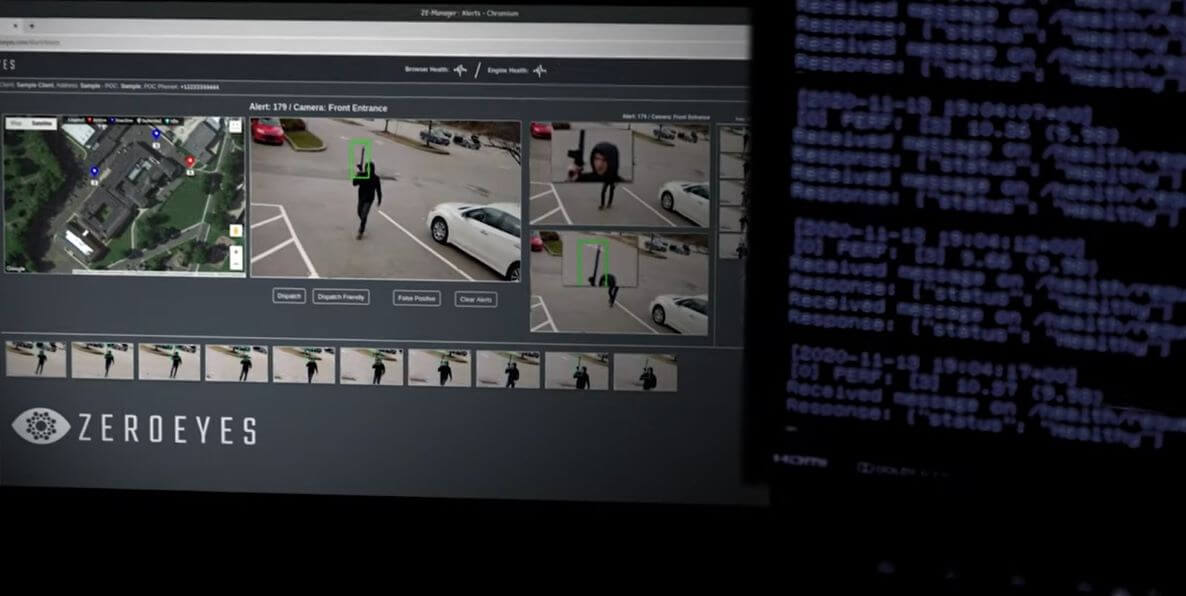

Now, when ZeroEyes’ system detects an object that looks like a gun, it sends a report to the ZeroEyes Operation Center (ZOC). Staffed by former law enforcement employees and military veterans, the ZOC receives reports when ZeroEyes detects a firearm. Then, one of the video monitors reviews the report, determines if there is a gun present, and alerts local law enforcement. The company has ZOCs located in multiple time zones. The system is manned 24/7, every day of the year.

Lahiff and Alaimo want to work with veterans and former law enforcement officials because they’ve been trained to detect guns and have experience acting quickly in emergencies. Hiring veterans also feels personal to them. They know how difficult it can be for former military personnel to transition back to civilian life and find purpose in their work.

“When veterans get done serving, a lot of them struggle with the transition and finding purpose and meaning again in their life,” Lahiff says. “We’re that home for them.”

The system detects firearms only. It does not use artificial intelligence for facial recognition. It also doesn’t store images of people’s faces, so schools can protect students’ privacy. Also, ZeroEyes’ focus on an object rather than a person helps the platform remain free of the racial and gender biases found in many AI systems.

“We are strictly object detection. And that only object we can detect is a gun,” says Alaimo.

In 2019, Rancocas Valley High School in Mount Holly, New Jersey agreed to serve as ZeroEyes’ beta customer. For one year, the ZeroEyes team worked nights in the high school’s hallways to test the system with local police departments in order to improve the software’s vision in different lighting conditions.

But, by 2020, when they had a fully functioning product ready, schools were shifting to virtual models as a result of the pandemic. Suddenly, there was decreased demand for on-the-ground security systems and a greater need to increase resources that helped students and teachers shift to remote learning.

So, Lahiff and Alaimo expanded their idea of a client base. Mass shootings have occurred everywhere in America, from supermarkets to religious institutions to movie theaters and concert venues. Why not set their sights on all of them?

They’re now working with Fortune 500 companies, corporate campuses, and the U.S. Department of Defense, in addition to school districts and universities. To protect client’s privacy, ZeroEyes will not share specific incidents when their service has detected firearms. Lahiff says that so far, it has flagged hundreds of images that helped customers involve the authorities and deescalate incidents.

Like many security services, ZeroEyes operates as a yearly subscription. Prices vary based on the number of cameras a business would like the software installed on, the number of locations it has and how long it plans to use the service.

Lahiff envisions a future where ZeroEyes’ technology is in every public building. He likened their product to other safety features like fire protection systems or carbon monoxide detectors.

ZeroEyes on SEPTA

Like the city at-large, SEPTA has struggled with gun violence over the past two years. Robberies and aggravated assaults on the transit system increased 80 percent between 2019 and 2021.

In July 2022, a 14 year-old boy was charged with shooting a 19 year-old on the eastbound platform of the Market-Frankford line at City Hall station. Last November, a man died after being shot 11 times on the Broad Street line near Fairmont Avenue.

Andrew Busch is director of media relations for SEPTA. He says that the system’s safety issues are exacerbated by staffing challenges brought on by the pandemic and the Great Resignation. He says the number of safety officers has decreased from about 230 employees to 210. SEPTA is actively recruiting new officers and has increased pay, Busch says, but hiring efforts are still ongoing.

SEPTA’s police currently monitor their live cameras, but with so many, it can be hard to pay attention to each one every second of every day. That’s where the ZeroEyes partnership comes in. By installing ZeroEyes software in cameras in high-traffic areas on the city’s subway stations, SEPTA is hoping to maximize the technology it already has in place to detect incidents and quickly deploy police to those locations.

Busch says every time ZeroEyes detects a firearm, SEPTA’s safety officers will receive a notification in three to five seconds. In December, SEPTA received a $4.9 million grant from the state to support the ZeroEyes pilot program.

“It is literally having more eyes on the system,” Busch says. “We’re very eager to see how it works on the system and how it can complement what we’re already doing with our police.”

Lahiff and Alaimo declined to share revenue figures, but say the business has consistently grown since their launch in 2019. They now have more than 120 employees and expect to be in all 50 states by the end of the year. In 2021, they raised $20.9 million in a series A funding round headed by Octave Ventures to help support their growth.

Lahiff envisions a future where ZeroEyes’ technology is in every public building. He likened their product to other safety features like fire protection systems or carbon monoxide detectors.

“ZeroEyes is going to be that next thing, but for gun violence … We’re going to be the fire alarm of the future and we’re blazing a path for that,” he says.

![]() MORE BUSINESS FOR GOOD FROM THE CITIZEN

MORE BUSINESS FOR GOOD FROM THE CITIZEN