The newly released annual report from PHDC, the Philadelphia Housing Development Corporation, offers an updated look at where Philadelphia is spending its Basic Systems Repair Program (BSRP) funds, and who the beneficiaries of that spending are.

The Basic Systems Repair program provides grants of up to $20,000 for low-income homeowners to put toward repairs to electrical, plumbing, heating and roofing systems. Eligible homeowners must meet certain income guidelines, which are updated annually by the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development. This is some of the most flexible housing funding around, and is especially necessary in a city like Philadelphia with an exceptionally high share of low-income homeowners who don’t have a lot of cash available for home maintenance emergencies.

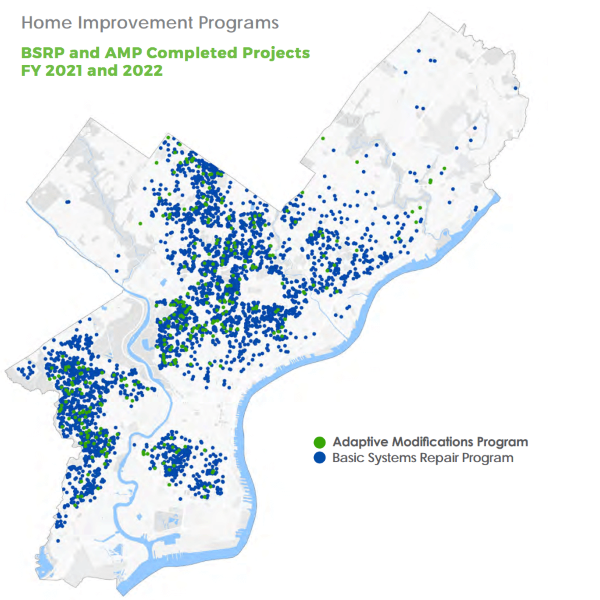

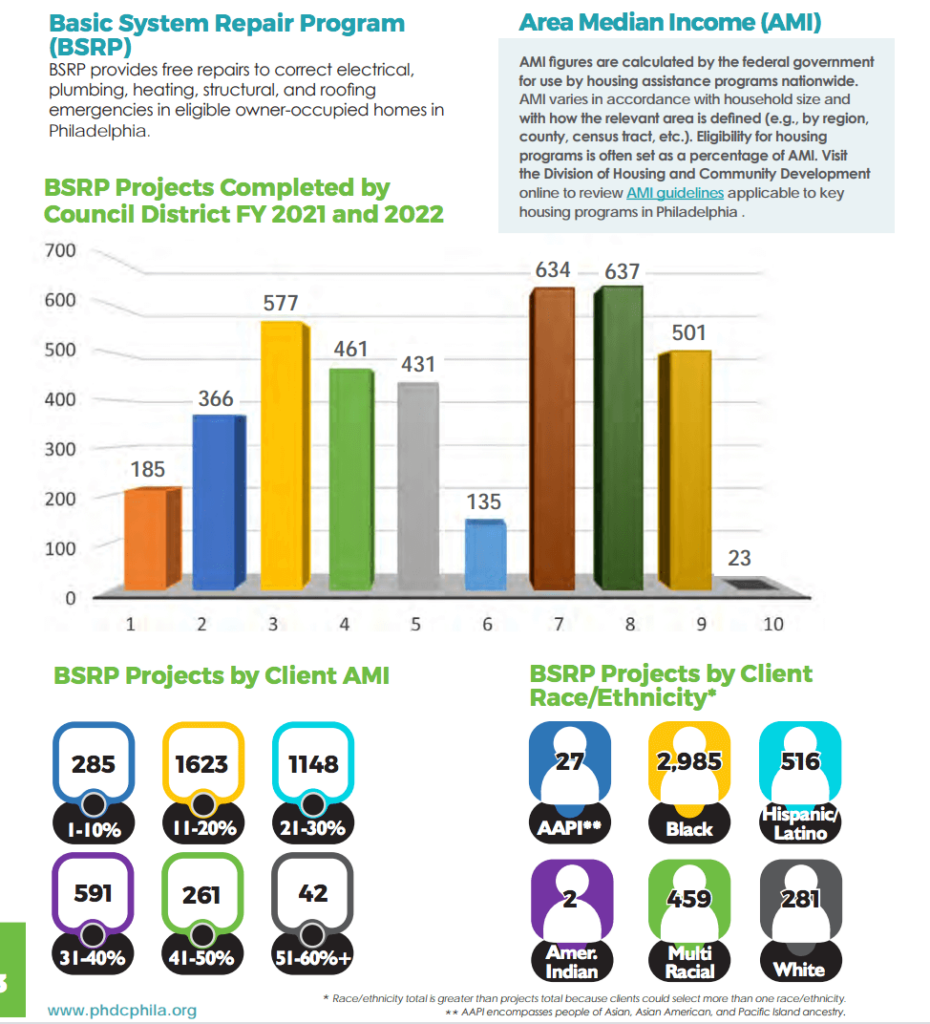

The report breaks down the number of grants by geography and City Council Districts, and also by race and income, and provides more confirmation that the BSRP spending has a very progressive distribution in its effects.

The Basic Systems Repair Program has recently enjoyed a run of positive media attention this year, starting with the release of a Penn study showing it’s associated with reduced violence in areas with higher concentrations of home improvements, and more recently as a result of the passage of State Senator Nikil Saval’s Whole Home Repair bill in Harrisburg, which would provide more funding for BSRP type programs to Pennsylvania counties, including Philadelphia.

BSRP lives in the city budget under the Housing Trust Fund, which also funds a whole raft of different housing initiatives, and has been a major consensus budget priority for different housing policy actors in the city. The HTF provides flexible funding for many different affordable housing initiatives, and was recently the funding source for the city’s shallow rent subsidy program.

In 2021, voters approved a city charter amendment, introduced by now-former Councilmember Derek Green, guaranteeing that the Housing Trust Fund would receive at least 1 percent of the city budget each year. And before that, City Council passed the Mixed-Income Housing (MIH) density bonus program that’s been very successful at creating a popular pay-for-density system where builders can build taller buildings or more housing units if they pay into the Housing Trust Fund.

For a sense of how successful the 2018 Mixed-Income Housing program has been at raising money for the Housing Trust Fund, consider that in 2018 when the program was created, City Council estimated it would raise $18 million within 5 years, or about $3.6 million a year.

The City hasn’t released a full list of all the projects that used MIH this year, but in just the last few months alone, there have been $10 million in commitments from just two building projects in University City — a 136-unit building at 41st and Walnut, and a 400-unit student housing building on the 3600 block of Chestnut. The Housing Trust Fund’s annual budget is around $60 million a year, so those two projects already account for about one-sixth of that total.

This is an important point to underscore about the redistributionary nature of the density bonus program, where people building in some of the highest-value parts of Philadelphia are essentially paying the City for permission to add more density, and then the money is going toward paying for people’s home repairs in generally lower-income neighborhoods, or underwriting deed-restricted affordable housing.

That seems like an unabashed success story from a progressive economic redistribution standpoint, but there are still some critics who don’t want to take yes for an answer.

That’s because another goal of the MIH program is to promote more in-building socioeconomic integration within especially larger housing projects in high-opportunity areas. And because the in-lieu fee options have been lopsidedly more popular, that’s led some critics to call for rebalancing the mix of incentives. There is also a sense that the in-lieu fee is still too low, even after it was already raised substantially in 2019.

Indeed, it has been very rare to see builders opt for the on-site option, although just last week, Jake Blumgart at the Inquirer reported on the largest project yet to provide the on-site units, in a 300-unit building in western Center City proposed by Parkway Corporation. That project will provide 31 affordable units rented at 60 percent of the Area Median Income.

If a large Center City project like this one made the in-lieu fee contribution instead of building affordable on-site, the Housing Trust Fund could have netted at least $6 million. That funding would have enabled 300 more households to get $20,000 in basic repairs. As we move into 2023, candidates running for Mayor and Council should have a position on this: Are 30 units of on-site moderate-income housing and 300+ repaired homes equally good outcomes?

More “integration machine” or “money machine?”

There are certainly some merits to the view that the program ought to be more of an integration machine than a money machine, but the success of the money machine model shouldn’t be written off, especially when that funding is able to be leveraged to support hundreds of home repair projects for low-income homeowners in need. It’s also creating a larger pot of money to help fund the kinds of deed-restricted affordable housing projects that CDCs and non-profit and affordable housing builders want to be able to access.

With so much of the displacement pressure in Philadelphia coming from this specific source — low-income homeowners forced to sell and move because they are unable to afford an emergency home repair — the ability to fund so many more of these types of repairs with the in-lieu fee money arguably deserves to take precedence as a political priority.

The good news is that thanks to the two new revenue sources — the Mixed-Income Housing density bonus program and the city’s 1 percent construction tax — there is now plenty of funding available in both the Housing Trust Fund and the Neighborhood Preservation Initiative such that City Council can afford to pay for many of their housing priorities.

If Councilmembers are interested in seeing more in-building integration, there are any number of things they might do to create more mixed-income or social housing. They could choose to spend some of the NPI funding — which comes from taxes on development — to buy in greater levels of affordability into some existing buildings.

Or they might decide to purchase some existing buildings and run them as mixed-income or social housing. Philadelphia is still about 7,000 public housing units below our federal Faircloth Amendment cap, so there is scope for all kinds of experimentation with non-market housing if the political will is there to fund it.

In the meantime, elected officials should be proud of their work creating a very lucrative stream of flexible housing funding for Basic Systems Repair and other very targeted spending, and do what is best to optimize that.

Jon Geeting is the director of engagement at Philadelphia 3.0, a political action committee that supports efforts to reform and modernize City Hall. This is part of a series of articles running on both The Citizen and 3.0’s blog.

![]() RELATED COVERAGE OF HOUSING IN PHILLY

RELATED COVERAGE OF HOUSING IN PHILLY