Like many of us, I’m looking forward to the end of winter, when I can open my windows again to the warmer temperatures outside. But like many urban residents, there’s a downside I’m less excited about: The return of the decidedly unpeaceful sounds of city life.

Last summer and fall, off and on for weeks, the distant sound of music filled the night in the Fairmount neighborhood. Cars equipped with subwoofers driving around Lemon Hill sent window-rattling bass in a radius of about a mile. Frustration about it filled NextDoor as well as a local Google Group. Some urged residents to call the police and log incidents, creating a scatter plot of where and how many people were affected. But most of us did nothing, feeling like this was one more noise we couldn’t control.

At some point in the fall the music stopped and I wondered how it was resolved — were there police involved or did the partiers move on willingly? Regardless, I was left unsure about how to think about noise pollution: Is this a problem of Karens who should live in the suburbs? Or is this a public health issue that no one should have to endure?

If you complain about noise in the city, you’ll likely be told to move. Noise is part of the package of urban living, right? But increasingly cities are pushing back on this narrative. Noise pollution, officially coined and codified by the EPA in 1972, has been known to cause not only hearing loss, but high blood pressure, heart disease, and increased stress in adults. A nonprofit in Paris found that living in the city’s noisiest neighborhoods reduced a high quality of life by three years due to the ailments caused by heavy noise pollution.

Living in a pervasively noisy neighborhood can lead to sleep loss and cognitive impairment in children, measured by memory, attention levels, and reading skills. Studies show that poor communities of color have higher levels of noise pollution, where airplanes, cars, trucks, and trains are the biggest culprits.

Yet the people who tend to complain about noise are whiter and wealthier. For example, gentrifying neighborhoods in Brooklyn saw an exponential rise in 311 calls. Kate Wagner writes in The Atlantic: “To gentrify a neighborhood also involves quieting it down. The desire for sonic control in and around the home is prioritized above the social fabric of the city, a practice exemplified by the targeting of arts and music venues that are cited as being partially responsible for neighborhood revival in the first place.”

NOISE project, guided by Cornell Lab of Ornithology researchers and independent community-led organizations who generate data to change policy where noise may be interfering with human health, questions why individual noise makers get punished rather than, say, airplane makers or transit authorities: “Violating noise restrictions in quiet zones was punishable by fines or imprisonment — however, only those with minimal power (people of color, low-income populations, and other marginalized groups) were actually punished, as opposed to punishing the powerful companies and corporations who were the largest contributors of noise.”

Can you keep it down over there?

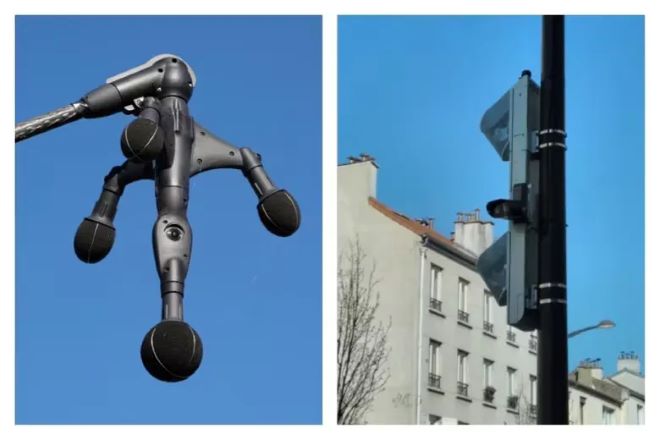

While there seems to be broad agreement that noise pollution has detrimental effects, there’s less consensus on what to do about it. Mumbai has instituted “no honking” days to draw attention to the problem of transport-related noise pollution. But more cities have taken a tech-oriented approach: Paris has begun to use “noise radar” to pinpoint high decibel levels and then bring offenders to justice. New York and Albuquerque are testing out that technology as well.

But while noise radar can tell police departments where the noise is coming from, that’s often not the challenge for cities. Is regulating noise the best and highest use of an often understaffed police force in cities with violent crime? And what are the appropriate consequences for noise makers? What if the offenders find community in an activity that happens to be very noisy? Welcome to the murky work of making the city quieter.

When I began exploring noise pollution, many sources led me back to Dr. Erika Walker, assistant professor of epidemiology and director of the Community Noise Lab at Brown University. The Lab explores “the relationship between community noise and health by working directly with communities to support their specific noise issues using real-time monitoring and exposure modeling.”

Walker writes compellingly about how communities near loud streets, highways, and transit are often inhabited by lower-income residents, who in turn shoulder the burden of our loud cities: “Black and Brown communities, in particular, face huge aural burdens. A very quick scan of our nation’s urban planning policies and practices clearly show that we as a country have a refined knack for dumping acoustical trash — like highways, airports, and truck depots — into the laps of those with very little power to fight back. Black and Brown lives have consistently been made to sacrifice acoustical environmental justice for the sake of everyone else’s convenience, oftentimes at the expense of their health and well-being.”

Walker’s work uses data to both expose inequities and encourage policy action. Three years ago, pandemic-induced quiet was shattered by the national trend of lighting fireworks. Walker found that Black and Brown communities were disproportionately affected by the fireworks phenomenon, robbing them of the Great Quiet. She described how Community Noise Lab then gathered noise complaint data from the City of Boston, “set out sensors and recorders to collect decibel levels and audio, crunched data, and reached out to the City Council with our findings, which then prompted the creation of the first fireworks task force in the nation.”

This approach, which helps to quantify the impacts of loud noise and puts a narrative to people’s feelings, is so much better than a NextDoor screed. It’s also better than other ideas I’ve seen of simply planting more trees and bike lanes — efforts that I imagine will help, but ultimately do nothing to address the root cause of the noise pollution.

Could Walker’s approach be a solution for cities struggling to satisfy competing groups when it comes to another growing subset of loud urban activities — ATV rides in many American downtowns or “siren contests” in New Zealand — that have significance to marginalized communities?

In Philadelphia, the noise of ATVs racing at top speed down city streets is a top quality of life issue for residents; driving ATVs in the city has also been illegal for over a decade. And yet, both reporting and community conversation have pointed to the fact bike culture is a joyous activity for bikers, some of whom might be vulnerable to other harms without the camaraderie of bike culture.

Policing has been ineffective: Police officers have noted that they’re unsure how to safely block bikers, especially when there are hundreds of them in a rally. Over the years, the city has confiscated hundreds of bikes to no effect. The city has said it is looking into possibly designating an area for ATV riding, but clearly not with any sense of urgency. In our quest for peace and quiet, it seems we’ve forgotten about the peace part — the negotiation required to come to a calm resolution. Without that, we won’t get the quiet we seek.

Diana Lind is a writer and urban policy specialist. This article was also published as part of her Substack newsletter, The New Urban Order. Sign up for the newsletter here.

![]() MORE URBAN QUALITY OF LIFE FROM THE CITIZEN

MORE URBAN QUALITY OF LIFE FROM THE CITIZEN