On October 28, a solar storm launched a coronal mass ejection towards Earth, hurling magnetic energy and plasma into our atmosphere. A spectacular aurora, a phenomenon generally only seen near the Arctic Circle, was visible in the sky as far south as Pennsylvania.

If you were in Philadelphia that week and expected to view this rare occurrence, you were disappointed. That’s because, as any Philadelphian knows, the night sky here is all but obscured by the electric lights emanating from streets, traffic, skyscrapers and other city buildings.

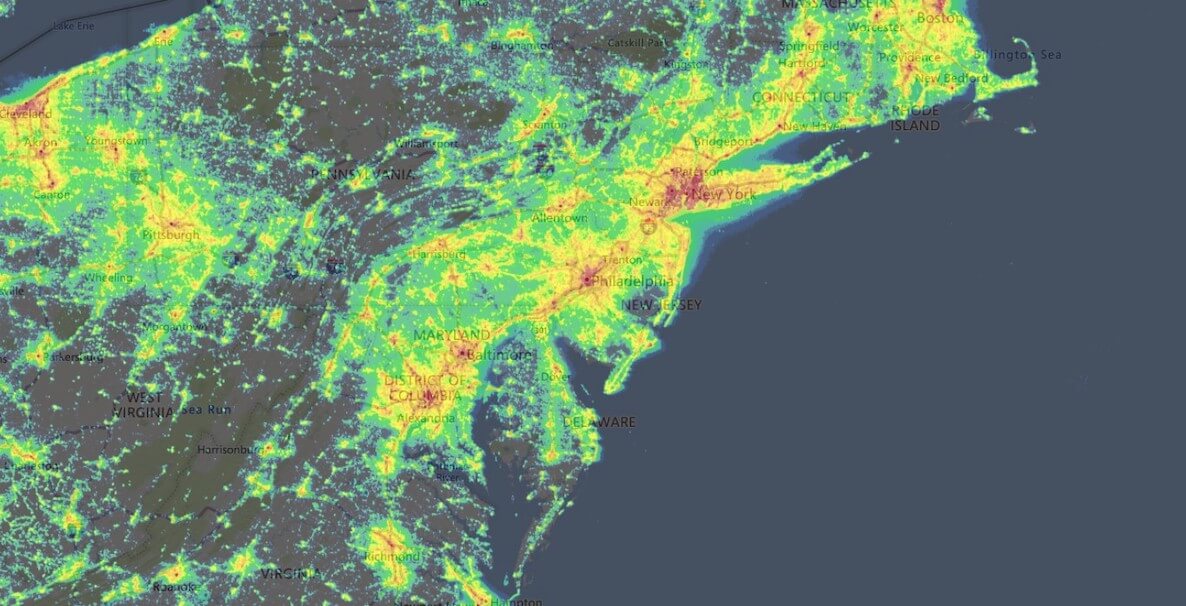

The Bortle Scale, developed to numerically measure the night sky’s brightness in a specific location, places Philadelphia well above a level 6, with the bulk of the city at an 8 or 9—the maximum. This means that for most of the city, the night sky is light gray or orange. Many constellations are faint or invisible. Galaxies and most planets can only be observed through a telescope and even then, are barely seen. In the most densely populated areas of the city, the sky is so bright that few stars are visible at all.

“It may be a 40 minute drive before you can see the Milky Way,” says Turnshek. “It makes it so that only people who are affluent can see the night sky, and that’s just not fair. I want dark skies for my kids. I want dark skies for everyone.”

While astronomers worldwide have been sounding the alarm about light pollution since the 1970s, ongoing scientific research has shown that artificial nighttime lighting is harmful to wildlife and human health.

In Pittsburgh, that urban phenomenon is set to change thanks to a new ordinance that makes it the first major American city to adopt lighting standards addressing light pollution. The law requires all new construction and renovations of city-owned buildings to comply with dark sky lighting principles, including replacing all the city’s street lights with fixtures that feature timers and dimmers, so they are only on when needed; are shielded, so light is directed at a specific area and is no brighter than necessary; and emit light with a color temperature below 3000 Kelvins (the measurement—with a scale of 1000-10000—used to describe the color temperature of a light source).

Architect Steven Quick and astronomer Diane Turnshek, both Carnegie Mellon University lecturers who are advocating for restoring the night sky, describe their goal as “Shrinking the Ring.”

“There is a ring around the city. It isn’t really circular, it’s more like an amoeba, but it’s a place where you can see the Milky Way outside the city but you can’t see it inside the city,” Turnshek says. “It may be a 40 minute drive before you can see the Milky Way. It makes it so that just people who are affluent can see the night sky, and that’s just not fair. I want dark skies for my kids. I want dark skies for everyone.”

Light pollution is unhealthy—and unsafe

The dark sky-friendly lighting standards are the work of the International Dark Sky Association (IDA), founded in 1988 with the mission to “protect the night from light pollution.” The organization educates the public and policymakers on how artificial illumination affects our communities. Recommendations are made based on decades of research into how light affects people and the environment.

Mike Lincoln is a teacher, photographer, and director of the Pennsylvania IDA chapter. “Our recommendations are more of a holistic approach to lighting,” he explains. “The recommendations come from engineering and lighting research, and show how lighting impacts not just visibility but also human health, and the health and migration of animals. Our knowledge has evolved as communities have met with and reported to IDA the impact of light pollution well beyond the night sky.”

In Pittsburgh, much of the effort towards dark sky lighting standards can be traced to the efforts of Turnshek and Quick. Turnshek, a recipient of a Dark Sky Defender Award presented a talk at TedX Pittsburgh on light pollution in 2015; she was part of Mayor Peduto’s transition team in 2013. Quick had worked with then-councilman Peduto when Quick was an architect, and then again on a street lights project for the Remaking Cities Institute in 2011. Peduto, for his part, was executive producer on the film Undaunted about the Allegheny Observatory, and had a vested interest in addressing light pollution.

“Diane’s and my work were the convergence of two separate ways of thinking,” Quick says.

The Pittsburgh ordinance applies only to city-owned property, which leaves around 75 percent of buildings unaffected. However, one provision mandates the city to create a guide for private property owners and developers on dark sky lighting standards. The city’s major attractions, such as zoos and museums, will install compliant lighting in future renovations and capital projects.

“The argument that less light is actually better is very hard to make, even though the police understand it, public safety professionals understand it, astronomers understand it, and we as architects understand it,” says Quick.

There is potentially infinite discourse on the philosophical and psychological impact of humans being unable to see the night sky, but light pollution does have more measurable negative impacts on people and animals. Problems stem from both quantity and quality of lighting in cities.

There are three basic aspects to efficient lighting: shielding, to ensure light is not diffused up and out to the sides instead of just where it is intended; temperature, which should be towards the amber side of the spectrum for health and safety, rather than stark white; and the amount of light.

“The amount of light that is standard in the lighting industry is much brighter than you really need to see well,” says Quick. “But if cities would step back and say that the quality of lighting is very important, that when we purchase lights, we want good quality light—that would shift the market.”

Daylight is on the blue end of the color temperature scale; it boosts alertness and plays a part in regulating our bodies’ sleep cycle. Excessive exposure, especially at night, disrupts sleep. Because it is also emitted by LEDs (including TVs), computers, and phone screens, most of our devices have blue light filters that shift the temperature to the warmer end.

Sleep Junkie conducted a study on how people in cities across the U.S. are sleeping, and Philadelphia came out on top…as the worst ranking city for sleep, thanks to light pollution and noise. Results indicated that Philadelphia has the 4th highest amount of light pollution out of the cities surveyed, and residents reported the second-lowest overall quality of sleep. Just 25 percent of adults in Philly are getting at least seven hours of sleep per night, and just 40 percent reported that they were getting regular, good-quality sleep.

Both plant and animal physiology is affected by the day-night cycle, and artificial lighting where humans live has had an outsize impact on other species as well. In October 2020, Philadelphians woke up to over 1,000 dead birds lying on the ground around just three blocks of Center City, having struck buildings overnight during peak migration season. The birds became disoriented by the light and were unable to navigate. In response, a voluntary program called Lights Out Philly was instituted, with both municipal and private properties turning off lights in unoccupied spaces overnight to avoid interfering with birds during migration season.

Contrary to conventional wisdom, brighter lights also do not reduce criminal activity. Our eyes adjust to dimmer light, allowing us to see by the light of the moon, for example. Intensely bright light, on the contrary, produces increased contrast and glare, which both serve to limit our vision. Two brightly lit buildings on a city street can produce an impenetrable dark space between them, presenting a real safety hazard.

“It’s insecurity lighting,” says Turnshek. “Public safety is really about thoughtful lighting.”

One oft-cited study by advocates for maintaining bright nighttime lighting was conducted in New York City in 2016. In partnership with the housing authority and the police department, researchers at the Crime Lab at the University of Chicago installed portable, diesel-powered 600,000 lumen-strong floodlights. (For comparison, a bright indoor lamp might emit 1,600 lumens.) The researchers placed an average of seven mobile light towers in each of 40 public housing developments, affecting 40,000 residents. According to the published data, crime was reduced up to 59 percent.

In the face of criminal justice inequities, redlining, lackluster school funding, and police profiling, why pursue something as relatively inconsequential as light pollution? The simple answer is that it’s low-hanging fruit for social justice. This problem has a technological solution whose benefits will be seen immediately in improved quality of life.

However, as Turnshek and Quick note, nothing about the experiment reflected real-world conditions, especially the fact that the amount of noise from the generators and light produced by these towers far exceeds anything used for street lighting, parking lots, or residential buildings. The drop in crime can easily be attributed to no one at all wanting to remain in the area while the light towers were in operation.

Still, fear of crime has led to brighter nightscapes in lower-income neighborhoods with predominantly residents of color than in wealthy white areas, according to a comprehensive environmental study of nighttime ambient light in the continental United States released in 2020.

“It’s a psychological and perceptual issue, it’s so hard to overcome,” says Quick. “We’re trying to deal with the issue of the public’s perception that more light is safer. The argument that less light is actually better is very hard to make, even though the police understand it, public safety professionals understand it, astronomers understand it, and we as architects understand it.”

In the face of criminal justice inequities, redlining, lackluster school funding, and police profiling, why pursue something as relatively inconsequential as light pollution? The simple answer is that it’s low-hanging fruit for social justice. This problem has a technological solution whose benefits will be seen immediately in improved quality of life.

“This is a problem that is easily solved,” says IDA’s Lincoln. “We created this problem through advancements in society, and with good intentions, and the time is now to solve that problem we have all created.”

The timing could be right for Philly

Philadelphia is already thinking about the future of illumination. In the interest of conserving energy and saving money, the City has been replacing traditional non-functional street lights with energy-efficient LEDs since 2015. But those LEDs are in the 4000 to 5000 Kelvin temperature range, enough to disturb sleep cycles. Dark sky standards recommend 2200 Kelvins as all that’s necessary for outdoor nighttime lighting.

Joy Huertas, deputy communications director for the Mayor’s Office, says the City has recently selected a vendor, and is in the early stages of planning to replace the rest of Philly’s 100,000 streetlights. That means this is a critical moment. “There will be ample opportunity to provide stakeholder input on the final plan,” says Huertas. “Once the contract is signed and approved by City Council, we will work with the selected vendor to complete a robust community engagement effort and analysis to select light fixtures.”

“People look at lighting as either utilitarian or a nuisance. We need to look at light the same way we look at air and water, as an ecological issue,” McGreeney says.

Light pollution, Huertas says, is one of the considerations in the City’s Municipal Energy Master Plan, though it is primarily focused on savings.

City codes for residential outdoor lighting do not specify a maximum brightness, but rather an energy efficiency minimum. Our current outdoor lighting standards are supposed to protect against excessive light and glare by limiting types of lighting and where light should be directed. Rotating and strobe lights are restricted, and lights must be shielded to prevent spillover beyond property lines. These regulations are aimed at motorist safety and nuisance control, rather than the health and welfare of people and the environment.

One positive indicator for Philadelphia getting serious about light pollution is the enthusiastic cooperation of private residential and commercial property owners with the Lights Out Philly initiative to protect migratory birds.

Bill McGreeney is an IDA Pennsylvania chapter board member who resides in Philadelphia. “People look at lighting as either utilitarian or a nuisance. We need to look at light the same way we look at air and water, as an ecological issue,” he says. “Philadelphia has good momentum for going green. You see the water department leading the way, but there’s also increasing bike lanes, more communal spaces, and creating a better living environment.”

Several groups are already working to increase public awareness and convince community leaders and organizations—like BioPhilly, the Franklin Institute, and the Audubon Society—to include the issue in their agendas and start to influence decision-makers in city government.

“We have to find a way to educate, to communicate in a way that speaks to everyone,” explains McGreeney. “The Audubon Society is light years ahead on this, but even after 20 years, it still took a mass bird die-off for anyone to even flinch, so there’s a lot of work to be done.”

To that end, the Pennsylvania IDA chapter created a petition on Change.org to make dark sky recommendations the standard statewide in outdoor lighting codes and recently met with State Senator Carolyn Comitta of Chester County’s 19th District to discuss the need for statewide dark sky legislation.

In Pittsburgh, Turnshek and Quick are currently seeking funding for a research project to photograph the city at night from overhead to document the extent of artificial light diffusing into the sky as pollution. Drones were able to capture footage of the CMU campus at night, but a city-wide survey would provide specific data on how much light is lost to the atmosphere and serve as a comparison tool once new compliant lighting is in broader use for other cities and researchers to measure impact.

Soon, they hope, Pittsburgh residents will be able to step outside and see the night sky. Bill McGreeney is unequivocal about the stakes: “We have to stop the war on the night. We have this perpetual daytime and it’s just not healthy, it’s not who we are as a species.”

![]()

RELATED

Zion National Park Milky Way, photographed by Matt Dieterich. Dieterich offers photography workshops. Learn more and check out his work here