Most educators do not conclude their time with students by saying “I love you.”

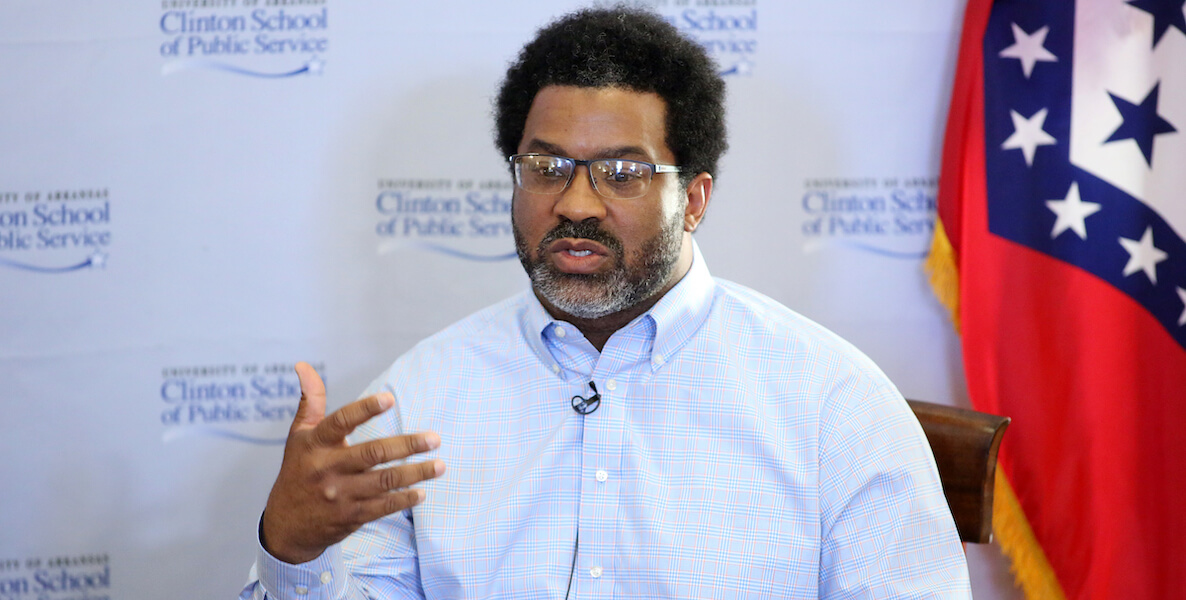

Richard Gordon IV is not most educators.

So on a recent summer morning Zoom check-in, it surprised none of the five students he’d assembled when he ended the call by saying: “I love you, I miss you, text me later!”

But even if he hadn’t said it, the kids feel Gordon’s devotion to them every day.

“He always tells me he’s proud of me,” says rising senior Jalen Paden. “I never had a good relationship with my principal before, but Mr. Gordon checks up on me and keeps me motivated. He’s open and honest and helpful.”

“Mr. Gordon is like a father figure to me,” says fellow rising senior Mujaheed Muhammed. “I could play around a lot, but Mr. Gordon always keeps me on the right path.”

Father Figure

Gordon’s name appears in local media coverage often. Most recently, this summer he was named the 2020-21 State Principal of the Year by the Pennsylvania Principals Association. He scored a perfect 100 percent on nearly every metric in the most recent Philadelphia Academy of School Leader’s 2019 teacher survey, which is compiled by the Neubauer Fellowship in Educational Leadership.

But Gordon is more than an award magnet: With nearly 25 years of urban education experience, he’s got the depth and expertise to validate the attention he attracts.

Among other accomplishments, he turned Paul Robeson High School for Human Services, a school with a 90-percent poverty rate and 100-percent minority population and one that the District had been planning to close in 2013, into one with a 95-percent graduation rate.

His success can be attributed to the formal programming he’s put in place—from mental health counseling to career mentorship to partnerships with Philly’s institutions of higher ed. But his progress all comes back to his unique gift of empathy.

“I am my students. I know exactly what they experience,” he says. “I understand what it means to come into a house full of cocaine and marijuana and strange people all over the house doing drugs. I know what it means to be a child of divorce and to come from a broken home. My father went to jail when I was in 7th grade, and then I didn’t see him again until 10th grade, and then after 10th grade I didn’t see him again until my junior year of college. I totally get the experience.”

Forging Connections

Gordon was working at the former Promise Academy at Roberts Vaux High School and SDP headquarters when he was tapped, in 2013, to serve as principal of Robeson, the two-story brick building at 41st and Ludlow.

“When I first got to Robeson, it was a community that felt fractured,” he says. So just as his peers in the business sector would do, he created a school-wide mission. “It’s about putting kids first,” he says. “You can’t work for me at Robeson unless you believe that and you actualize that every single day in our building. We work together to ensure that our students understand that everything we do is geared toward their welfare and well-being.”

The school is a stone’s throw from Penn, Drexel and the Science Center; Gordon was shocked to come to the school and find out that none of them had a presence there. He got to work changing that, and forging countless other connections for students. He secured opportunities for students to enroll in college-level classes at Community College of Philadelphia (CCP), Penn, Drexel. Among other programs, rising senior Saniah Aaron participates in a medical research internship program at CHOP.

“Mr. Gordon is always looking for programs and different mentorships or internships that are going to help us,” Aaron says. “He knows his students, so he’s going to tell you about a program that he knows will be a good fit for you.”

The list of opportunities he’s cultivated rivals that of many private independent schools. Notably, as he’d done at Vaux, he established a mental health program that students readily use for group and individual therapy.

“When I brought the idea to Robeson, it just blew up like gangbusters,” he says.

![]() Gordon has a mental health background, having worked as the weekend director at a mental health hospital program in Baltimore County; he believes in its importance and is aware of the hurdles around it. “One of the things that happens in minority communities is that there’s a stigma with regard to mental health support. However in our school, it’s not something kids are ashamed of—they talk about going to therapy the same way they talk about going to lunch.”

Gordon has a mental health background, having worked as the weekend director at a mental health hospital program in Baltimore County; he believes in its importance and is aware of the hurdles around it. “One of the things that happens in minority communities is that there’s a stigma with regard to mental health support. However in our school, it’s not something kids are ashamed of—they talk about going to therapy the same way they talk about going to lunch.”

And while Superintendent Dr. William Hite and SDP have been committed to rolling out mental health support in schools, Robeson has been doing it for five years, exceeding initial capacity; they now have a full-time therapist in their building five days a week, as well as a part-time therapist and an intern. “Having had the opportunity to merge the two entities—education and mental healthcare—has really worked wonders for our students,” he says.

Build Your Own Brand

The Robeson motto is “build your own brand.” What it means comes down to this, says Gordon: Tell us what you want to do, and we will help you find a pathway there. It’s how Robeson individualizes school for students and makes it a place they want to come from all over the city.

Students who express an interest in college must apply to five of them. Every student is required to apply to CCP. (“We want to make sure 100 percent of our students are accepted so that you have an option,” Gordon explains.) Anyone who plans to go into the workforce must meet on Fridays with Russell A. Hicks, the head of Ebony Suns LLC.

“No matter what people go through at home, what people go through outside of school, you’ll come to school every day, you’ll see Mr. Gordon right there, ready to shake your hand, give you a hug, and that puts a smile on your face.”

Gordon has a line item for Hicks each year in his budget, to keep him on contract as a business consultant. Funding for Mr. Hicks and other programs comes from Gordon’s creative budgeting and the budget increases the school has received as enrollment has grown. They started in 2013 with just over 250 students; over the past six years, they’ve averaged more than 305.

Hicks takes 11th and 12th grade students to visit and learn from local businesses and leaders, from welders to barbershop owners. He helps students write business plans and make connections.

One student shared his dream of NASCAR racing; to Gordon’s delight, Hicks got the student connected to a professional race team, and that student is now preparing to start on the amateur circuit when Covid-19 restrictions are lifted. Another student joined the Marines, and recently stood guard over John Lewis’s body during funeral proceedings in Montgomery.

“That’s a Robeson kid. He graduated from a school that wasn’t supposed to exist and he’s in the throes of history right now,” Gordon says, getting choked up. “I’m so proud of this kid.”

Gordon believes in his program so much that he even invited his own niece, Makayla Harris, to enroll in the school. After struggling with bullying for her entire school career from first grade on, she’s thrived for her four years at Robeson, and recently graduated.

“It’s really like a sanctuary,” says Muhammed. “No matter what people go through at home, what people go through outside of school, you’ll come to school every day, you’ll see Mr. Gordon right there, ready to shake your hand, give you a hug, and that puts a smile on your face. The vibe in that school is genuine, and Mr. Gordon always looks out for you and your family, no matter what.”

Before he came to Robeson, Muhammed says that all he really valued was athletics. “Mr. Gordon put me in a computer science program, and now that’s what I started to value more. Now I have something else to fall back on if football doesn’t work.”

Coming to the Table

A promotional YouTube video for Robeson shows a wall of snacks that Gordon keeps in his office; students regularly wander in, for Cheez-Its and frosted animal crackers. Sometimes, Gordon will order pizza for students. “I’ll sit at my desk and do my work, but at the same time I’m watching them eat and talk, and they are hilarious, and I can see the stress and anger and frustration melt off of them, just from the simple idea that they can take a break, in school, and be themselves. Everything is not about academics every moment of the day. We are investing in people. And that motivates them to want to work hard and do their best.”

Gordon is outside the building every single morning, welcoming his kids, rain or shine. On the first day of school, he hires a DJ. Every student in the building has Gordon’s cell phone number—and they use it. If, say, a student gets thrown out of her home at one in the morning, he can’t go and pick her up, but he can arrange for an Uber to bring her to another friend or family member’s home, to keep her safe until the school can work with her the next morning.

“It takes a lot of time, a lot of investment, a lot of creativity,” Gordon says. “I’m constantly working, day, night, weekend. But it’s worth the investment. We cannot ask kids to come to school every day knowing that they have four other problems that, quite frankly, are more important than school.”

Where many students in wealthier areas can prioritize school, Gordon has an Honor Society student who’s had to sacrifice her grades to pick up more hours at work, to take care of a parent with a disability; he has a student who needs permission to arrive a full 90 minutes after the first bell, to accommodate the fact that she gets her younger siblings to school while her mother struggles with substance abuse.

“I have such amazing kids, and I have the best staff who understands everything I’m trying to do for them,” he says.

One thing he won’t do: let them off easy.

“You can’t work for me at Robeson unless you believe that and you actualize that every single day in our building,” Gordon says. “We work together to ensure that our students understand that everything we do is geared toward their welfare and well-being.”

He pushes them because he feels he is them, has been in their shoes. Growing up in Camden, New Jersey, Gordon’s parents divorced when he was eight. When he was in 7th grade, his father, with whom he’d been living after the split, didn’t come home one night. Gordon took it upon himself to secure food from a neighbor for himself and his younger brother, keeping it warm over candles. The next morning, he got his brother, and then himself, off to school. When his father didn’t return the next night, Gordon sought out Dad’s ex-girlfriend, and learned that his father was in jail—with no sign of making bail.

He called his mother, who was living in Philly, and moved in with the woman who would go on to wake up at 5am every day to make sure Gordon still made it on time to his school in New Jersey. It was in New Jersey, during a 12th grade civics class at Pennsauken High School, where Gordon realized he wanted to be a teacher.

“I had this teacher, Richard Sia, and he was absolutely hilarious and weird and strange, and hard too. He had a hard class, it was difficult, it was challenging, but you didn’t feel like it was stressful. He provided the rigor, the entertainment, the humor,” he says. One day Gordon looked up and decided that’s who I want to be.

He’d go on to become just that, studying at Lincoln University and working in three large urban school districts—-Baltimore, D.C., Philly—-as a teacher and administrator. He spent two years in the office of alternative education with SDP, and was the principal of the old Vaux HIgh School before it closed. He’s seen first-hand the importance of restorative practices, the negative consequences of zero-tolerance policies, the trouble with suspensions that don’t teach anyone anything.

“Consequences have to be learning experiences for our kids so that they know how to correct it next time,” he says, or how to reach out to an adult when they’re in over their head. He believes strongly in mediation and collaboration, involving families and bringing everyone to his office table.

But he also knows what the real world is like: “What I try to impart to my students is that I understand, but at the end of the day, the world doesn’t stop moving forward. So it doesn’t give you a built-in excuse not to be successful. Unfortunately, until the world is fair, we still have to live our lives. So you can’t allow yourself to live in excuses and I can’t accept excuses.”

Investing in Schools

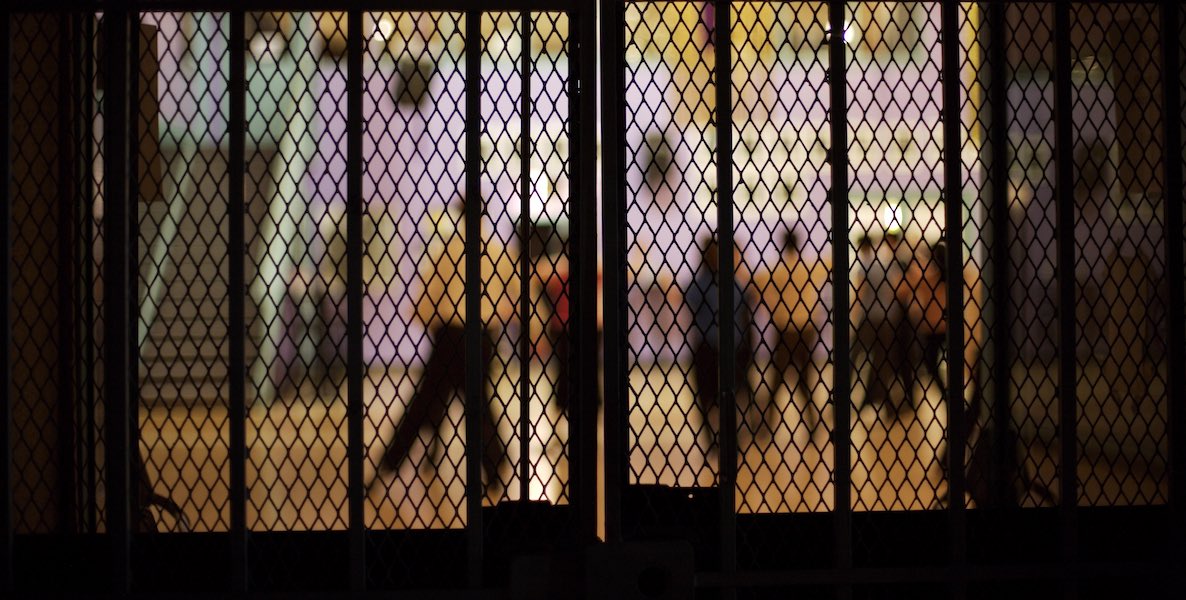

With 50 percent of his graduates going on to college and the other 50 percent choosing the military or workforce, Robeson grads will continue to move along with the world. And Gordon wants Philly, all of its sectors, to rally behind them. He’s frustrated that the city is grappling with the same issues that have been going on for decades. “What we wind up doing is policing or managing poverty, rather than problem-solving. And that’s the problem,” he says.

He believes the way to address poverty and its fallout—high school dropout rates, crime, gentrification that prices people out of neighborhoods—is to invest in anchor institutions, like schools.

![]() “In order for municipalities to truly combat poverty, I believe there must be a collective community will to invest in anchor institutions that serve the most impoverished and vulnerable communities, which are primarily communities of color,” he says. “Schools are anchors of the neighborhoods they serve.”

“In order for municipalities to truly combat poverty, I believe there must be a collective community will to invest in anchor institutions that serve the most impoverished and vulnerable communities, which are primarily communities of color,” he says. “Schools are anchors of the neighborhoods they serve.”

He holds Nashville, Tennessee, up as a model: During the Obama era, that city used its stimulus money from the financial crisis turndown to invest in the renovation of buildings and dedicated itself to a coherent philosophy: Career Technical Education for all non-magnet schools, and workforce development partnerships and internships with business associations so that students could have real-world experiences and potential job opportunities resulting from their training.

Philly, by contrast, didn’t plan for the long term. “And so while Nashville continues to make strides in education, Philadelphia is stuck in the same place where it’s been for the most part over the last 10, 20 years,” he says.

He laments that, prior to Dr. Hite’s arrival, SDP has been unable or unwilling to focus on the importance of capital improvements. His students, he feels, have done everything the District asks of them—and yet the school still operates without basic needs like air conditioning.

In recent months, Gordon has committed to various equity advocacy groups, to sharpen his ability to speak up on matters just like this.

And while the system falters, he’ll continue to do everything he can to turn things around for his students. With music and handshakes, with hugs and texts and I love yous.

“There are challenges, don’t get me wrong,” he says. “But I think those challenges are the things that make our students strong. They’re stronger than we give them credit for.”

Says Paden: “Mr. Gordon is the best principal in the world—that’s all you gotta know.”