It’s no secret that Kensington is in a bad way. For years, the North Philadelphia neighborhood has been the epicenter of the East Coast’s opioid epidemic, where drug traffickers rake in a billion dollars per year and leave residents to bear the brunt of rampant addiction, poverty, homelessness, and crime.

Philadelphians know about Kensington. So does the world, it seems. Those of us who have not been to K & A have certainly seen it on the news or online. By now, we’re all aware: Kensington is in crisis, with no resolution in sight.

But, in recent years, Kensington’s booming drug trade has spawned another shameful cottage industry: trauma porn, also known as poverty porn. Trauma porn is any kind of media that exploits impoverished communities for shock value, often cashing in on human suffering.

These days, it’s as common to see volunteers passing out food on the sidewalks of Kensington Avenue as it is to see people prowling the pavement with iPhones, recording people suffering in public view.

Kensington has become ground zero for trauma porn in America. Even the most venerated media outlets, such as the New York Times, have been accused of peddling poverty porn. Over the past few years, the phenomenon has spiraled out of control, as independent social media videographers — many of whom consider themselves journalists — come to the neighborhood expressly to capture scenes of human misery.

These days, it’s as common to see volunteers passing out food on the sidewalks of Kensington Avenue as it is to see people prowling the pavement with iPhones, recording people suffering in public view.

On the one hand, these videos are bringing sustained, widespread attention to an ongoing humanitarian crisis unfolding on the streets of our city. On the other, they are exploiting the very people who are suffering the worst of that crisis. But, until now, no one has really asked: Why are there so many of these videos online, and how do they amass so many views? And what impact do the videos have on Kensington’s residents, from those living in the streets to those assisting them?

Why do people watch this stuff?

By now, most of us have felt the pull of recommendation algorithms firsthand: Shed tears over a clip of Bryce Harper’s 2019 walk-off grand slam, and you’ll have Philly sports highlights in your recommended videos on YouTube for eternity. TikTok, Instagram, YouTube keep us scrolling by serving algorithms that adeptly send us down rabbit holes.

The same dynamic is at play with trauma porn. Watch one video of people huddling around a garbage can fire on Kensington Avenue, and you’ll receive a recommendation for one of someone injecting fentanyl, then for one of someone being saved from an overdose with Narcan, and so on. There’s an effectively infinite supply of such videos on YouTube, and for one reason or another — be it morbid fascination, voyeurism, cruelty, or empathetic curiosity — millions of viewers have taken the algorithmic bait.

Psychologists have many theories for why people are tempted by such content, but there’s a surprising shortage of empirical research on the subject. A particularly compelling explanation has been advanced by Dr. Matthew Goldfine, a New York-based clinical psychologist, who told Women’s Health: “Maybe someone was jogging at 4 am in Central Park and got murdered, or maybe they got into a car accident while talking on the phone. You want reassurance that this couldn’t happen to you because you’re safer than that.”

Applied to Kensington trauma porn, Goldfine’s theory would entail viewers feeling reassured that they’re better off than the people in the videos — i.e., no matter how tough my life may seem, at least I’m not shooting heroin under the El.

Why do people film it?

By my count, a minimum of 69 YouTube channels feature Kensington-specific trauma porn. Several of these channels meet the criteria for monetization via the YouTube Partner Program, through which creators typically earn between $2 and $12 per 1,000 views. Roughly a dozen of these channels are entirely devoted to Kensington. One received over 250,000 views for videos uploaded over the past month alone, which could translate to between $500 and $3,000 in advertising revenue. And that’s not to mention income from premium subscription fees or linked Patreon pages.

But a quarter of a million views isn’t remarkable for Kensington trauma porn. Multiple channels have subscriber counts in the hundreds of thousands, and many videos garner upwards of a million views. Even those uploaded by smaller accounts amass disproportionately high view counts, which seems to suggest that YouTube’s algorithms are amplifying the videos.

And it’s easy to see how: Almost all of their titles incorporate a common set of keywords. Phrases you see over and over again include “Kensington Zombies,” “Streets of Kensington,” and “Philadelphia Badlands.” Another commonality is thumbnail selection: graphic photos of someone mid-injection, or nodding out while standing up (doing the “Kensington lean”), or sexualized screenshots of female sex-workers emaciated from addiction.

Multiple channels have subscriber counts in the hundreds of thousands, and many videos garner upwards of a million views.

Further evidence that YouTube’s algorithm amplifies Kensington trauma porn: even channels that otherwise have nothing to do with documenting homelessness or addiction — vloggers from Indonesia, Russian bots – have uploaded (presumably stolen) videos titled “Streets of Kensington,” in an apparent bid to attract new viewers. One channel even used Kensington keywords in the titles for a series of Minecraft livestreams.

How is this allowed? YouTube doesn’t say much about mistitling videos. But its community guidelines and monetization policies have rules that prohibit featuring hard drug abuse, highly sexualized content, or “scenarios that intend to shock or disgust viewers.” There are also laws against filming anyone who’s unable to consent. But such guidelines are nuanced. YouTube allows all of the above for purposes of “authoritative news reporting” — and it’s not always clear which videos should qualify for this exception.

Who’s doing the filming?

Often a YouTuber from out of town will go to Kensington and walk or drive its streets for a day trying to capture footage. But several channels are run by people who live in the area and who hit the streets on a regular basis.

Jon McCann, known online as The Philly Captain, is a former Kensingtonian who goes back once or twice a week to shoot video. He says he’s appalled by the misery and lawlessness he sees, and blames politicians in the district, like longtime Councilmember and now mayoral candidate Maria Quiñones Sánchez.

“I want to hold people accountable,” McCann said recently on The Dom Giordano Program on 1210 WPHT talk radio. “I want kids from Conwell Middle School to be able to walk three blocks to the El and not see one person passed out, nodding out, shooting up, selling drugs … If that stuff was going on in Rittenhouse Square, I don’t think it would be allowed. So my thing is: What are we doing to these kids in Kensington?”

McCann argues his videos have benefits beyond awareness and accountability. He says they’ve served as proof of life for people looking for loved ones. And some viewers, he says, watch as part of an effort to stay sober, to remind themselves of how grueling life will be if they succumb once again to their addiction.

But his videos are often shot through with sensationalism. Two of his channel’s top three videos are titled “REPORTING A DEAD BODY TO THE POLICE.” In neither instance is someone dead, just in need of help. Neither video reveals that twist until the end — which is perhaps not the most effective way to show proof of life to a loved one who may have tuned in.

If you film it, they will watch; if you watch it, they will film.

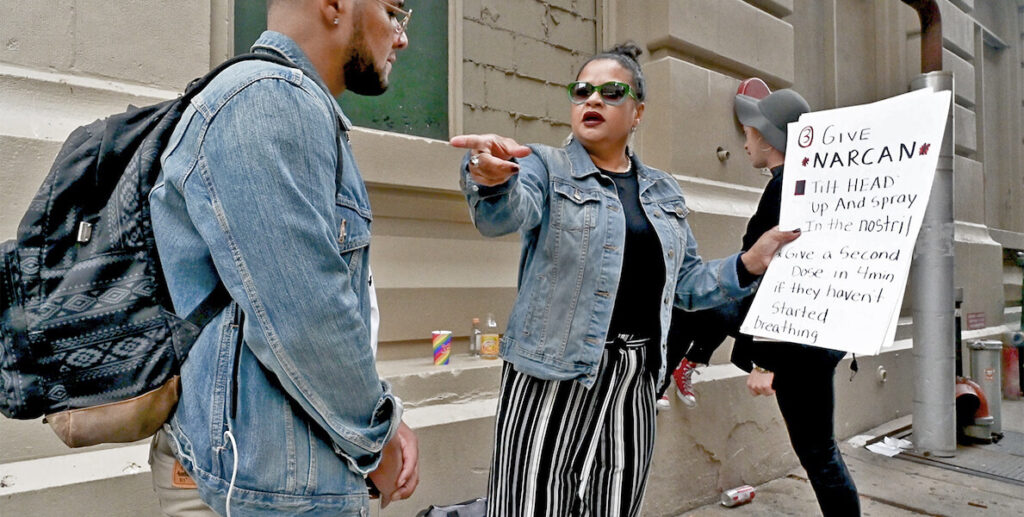

Rosalind Pichardo, the founder of Operation Save Our City who has administered naloxone to over 900 people in Kensington, was once misled by a post like this. Pichardo hates seeing trauma porn on YouTube and social media. She doesn’t understand why anyone would want to watch — or profit from — it. She says capturing and posting videos of people suffering from addiction rubs salt in the wounds of both the people experiencing addiction and the people who love them.

A few years ago, she saw a photo of her cousin on a popular Kensington-themed Instagram account. The caption read “rest in peace.” For days, she searched for her cousin in morgues and hospitals. Then she ran into him at a store. “It’s heartbreaking to think someone you love died,” she says, “I’m glad he was alive, but I was mourning because of a lie.”

Pichardo sees people filming in Kensington all the time in the course of her work. Often she confronts them, asking: Did this person consent to being filmed? She’s known for telling the people she helps: “There’s life after addiction.” So what happens, she wonders, if someone goes into recovery, looks for a job, and gets recognized from a viral video titled “Kensington Zombies?”

Like Pichardo, Dawn Killen, director of outreach and community events at a Kensington-based nonprofit Angels in Motion, constantly sees people filming the neighborhood’s homeless residents, whom she says often get upset at those holding the camera. She’s had to ask filmers to step aside while administering naloxone to an overdosing person.

But, usually, she doesn’t confront them: She doesn’t want an already tense situation to escalate. If she feels the need to step in, she’ll do so indirectly, asking them if they need naloxone or want training on how to administer it. Usually, Killen says, that’s enough to get them to leave or back off a bit. But they rarely accept her offer for Narcan. “That tells me all I need to know about their intentions,” she says.

Humane portrayals

It’s not that Pichardo’s against all filming in Kensington. As described in the Citizen, she’s been the subject of documentaries about her work in the neighborhood. But in her films, the faces of subjects are blurred out. She wants to portray the folks she helps as human, as hopeful. And, true to this philosophy, she once stopped a camera crew from filming someone who was overdosing.

Pichardo is not the only one documenting the crisis in a nuanced, humane way. Temple University’s student-led digital magazine, 1217, was the brainchild of Jillian Bauer-Reese, who founded the community newsroom Kensington Voice after being disheartened by what she saw as sensationalist coverage of the neighborhood in the New York Times.

In 1217 — named for the 1,217 people who died of drug overdoses in Philadelphia in 2017 — student journalists covered every aspect of the city’s addiction crisis: family relations, harm reduction efforts, the criminal justice system, homelessness, recovery, and more. The project is anything but reductive — and yet, some might argue that it’s limited in reach and emotional potency because it’s all written word and still photography.

Rosalind Pichardo says capturing and posting videos of people suffering from addiction rubs salt in the wounds of both the people experiencing addiction and the people who love them.

Artist Jeffrey Stockbridge first visited Kensington in 2008 and remembers feeling overwhelmed by suffering on such a grand scale. So, he set out to understand “how and why people became addicted to drugs and what would push them to engage in prostitution or crime in order to supply their habit … the most shocking things I saw, I generally didn’t photograph, because it wasn’t my goal to sensationalize other people’s suffering.”

Stockbridge’s Kensington Blues series combines written word, photography, audio, and video to show the humanity in Kensington’s opioid crisis. Stockbridge hasn’t completely escaped criticism, either; his photos of recognizable people engaging in drug use have struck some as exploitative. But there is a difference between his images and what you find with the stroke of a key on YouTube.

The future of trauma porn in Kensington

The emergence of new, highly addictive short form video platforms like Instagram Reels, TikTok, and YouTube Shorts — the latter of which pays out monthly bonuses as high as $10,000 to popular content creators — threatens to further boost the popularity of trauma porn. And the savvier these platforms and their algorithms get, the wider an audience these videos will reach.

If you film it, they will watch; if you watch it, they will film.

On the other hand, platforms have proven they’re capable of recognizing and taking down content in this lane that violates their policies. Meta has acted to shut down a number of Kensington trauma porn Instagram accounts. As for YouTube … in response to a request for comment, a YouTube representative asked for links to videos referenced in this article. Those links were provided, along with a list of all 69 accounts that feature some form of Kensington trauma porn. After multiple follow-ups, the company had no response.

What can you do?

If you see content that clearly violates moderation policies, there’s a button you can click on every YouTube video to report it. Google, YouTube’s parent company, has a department that reviews these reports 24/7.

Should you be walking by someone taking a video of someone in trauma in Kensington — or anywhere — you can take Dawn Killen’s lead and intervene indirectly and non-confrontationally. Ask them if they want necessary supplies like water or naloxone, or offer to connect them with organizations like Angels in Motion. You could try asking a police officer to assist you, but Killen says she never has, as “they have their hands full.”

Alternatively, you can absorb the more humane depictions of Kensington’s humanitarian crisis, let it inspire you to help, and amplify it in the hopes it inspires others to do the same.

In 2018, Sam Woods Thomas, then at the New Kensington Community Development Corporation, wrote a powerful op-ed for WHYY with a message we should remember.

At stake in all this, is the soul of a place where Philadelphians have made a living, shopped and socialized for generations. The dualities are stark; Kensington is still an avenue of pain and trauma, ground zero for the opioid crisis, prostitution, and poverty. This should not be ignored, and is, in fact, impossible to avoid. This street wears its heart on its sleeve, triumphs, and failures on full display. However, sensationalizing poverty, fetishizing small businesses, and minimizing the collective efforts of a community on the rise are the cheap tactics of bad journalists. Stop writing about Kensington Avenue like it’s Mordor. Give your readers the whole story. Anything else is tantamount to poverty porn and disrespectful to the people who dedicate their lives to making Kensington Avenue a better place.

To my mind, Woods Thomas’ words don’t apply to journalists alone. They apply to all of us, including YouTubers, passersby, developers, politicians, and viewers on the other side of the globe. The crisis in Kensington certainly warrants our attention — but our full attention, given to every complexity we can parse and to every person implicated, in all their human dignity.

![]() RELATED STORIES ABOUT THE KENSINGTON NEIGHBORHOOD

RELATED STORIES ABOUT THE KENSINGTON NEIGHBORHOOD