Not many Americans can name a favorite Harriett Tubman statue off the top of their head.

Only a dozen statues exist of the Underground Railroad hero who ushered 70 enslaved people to freedom during the 19th century. Most of those 12 stand along the path she took from Maryland to Canada during her rescue missions. Andrew Jackson, who enslaved close to 100 people at the time of his presidency, has about as many, including a major memorial in the U.S. Capital. Although many Jackson memorials are being removed, his likeness lingers, including on the $20 bill, despite a push for Tubman to replace him.

That’s not to say people haven’t seen Tubman’s statues. The Journey to Freedom, the monument that traveled to Philly earlier this year, has received close to 4 million visitors. But, for as iconic, as historically significant, as heroic as Tubman was, her depictions are relatively few. Again, few people can name their favorite.

As our country fights to save its democracy, Johnston’s message of freedom for all feels particularly resonant.

Philadelphia-based walking artist Ken Johnston isn’t most people. He not only has a favorite Tubman statue — the one in Wilmington, Delaware, where she’s depicted with abolitionist and fellow Underground Railroad leader Thomas Garrett — but he’s also visited all of the memorials located on the route she walked while leading her three younger brothers to freedom.

This year, Johnston walked 450 miles from Harlem to St. Catharines in Ontario, Canada, where Tubman lived in freedom in, in recognition of the 200th anniversary of Tubman’s birth. His journey was the last leg in a more than 800-mile, three-segment walk he began in 2019.

Johnston walks aren’t just for himself. They’re to bring attention to people’s fights for freedom across the world — from Belfast, Ireland, to the U.S. and Puerto Rico. As our country fights to save its democracy, Johnston’s message of freedom for all feels particularly resonant.

“It’s about identifying the lives of these individuals who were once enslaved across this region — Pennsylvania, New Jersey, New York — and trying to remember their spirits, remember that they existed,” he says. “We were erased from history. Our history is a redacted history that obscures the violent destruction of lives and cultural traditions, communities, and other markers of identity, including burial traditions and gravesites.”

With his journey behind him, Johnston is bringing his passion for Tubman home to Philly. He’s one of a number of Philadelphians advocating for the City to put up a permanent memorial to her.

A walk across all of Massachusetts

Johnston began completing long walks in 2017. Back then, he was living in Massachusetts, working a desk job in human resources and searching for ways to be more active. He didn’t want to just go to a gym and run on a treadmill for 40 minutes. He wanted to be outside, engaging with the landscape around him.

So, he decided to see if he could walk across Massachusetts. He started from the Southwest corner of the state in Williamstown with a goal of completing eight to 10 miles that first day. He walked 12. The next day, he came back to the place where he left off, and continued.

“I realized as I was doing this walk that history was playing out in front of me,” says Johnston. “And I remembered this quote by Harriett Tubman. She said, ‘If you want to taste freedom, just keep going.’”

Johnston didn’t tell anyone about his walk at first, too nervous he wouldn’t be able to make it all the way. Every weekend, he’d go back to where he left off and begin walking again. After about three weekends, he’d made it one third of the way across the state.

“That’s when I realized that I can do this. I could complete this walk,” he says.

It took walking every weekend from June to September, but he made it across Massachusetts to the tip of Cape Cod. He recalls passing monuments to Union Soldiers and thinking about how so much of the ground he walked over had played a crucial role in American history.

Johnston has always loved studying the past. Growing up in Germantown in the 1960s, he remembers going to Civil Rights protests with his mother. When he attended college at the University of Massachusetts Amherst, he studied history and African American studies under James Baldwin. But walking over historic sites was a different experience entirely. He found himself thinking about how people living in the 17th, 18th and 19th centuries might have walked from city to city. He thought of enslaved people who escaped and traveled North on foot to freedom.

“I realized as I was doing this walk that history was playing out in front of me,” he says. “And I remembered this quote by Harriett Tubman. She said, ‘If you want to taste freedom, just keep going.’”

Keep going he did. Between 2017 and today, he’s completed nine major walks, including his three-segment walk honoring Tubman. He’s walked in places as far spread as Ireland and Puerto Rico. He’s walked in Philly, Baltimore and New York.

Walking as art

Johnston, who moved back to Philly in 2019 to be closer to family, calls himself a walking artist. He is a member of the Walking Artists Network, a group formed in 2007 to explore how walking is used as a critical practice and as performance art. Walking Artists walk as a means of engaging with art, architecture, history, anthropology and cultural geography.

Johnston wants his walks to honor the history of people fighting for their freedom. When he walks among cities visited by Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. during the Civil Rights Movement, he symbolically retraces the steps of racial justice leaders from the period. His 71-mile trek from Belfast to Derry in Northern Ireland allowed him to reflect on discrimination outside of the U.S.

The blog detailing his walks is named Our Walk to Freedom after a 1963 Civil Rights March held by the Detroit Council for Human Rights. With 125,000 attendees, it was the largest demonstration for freedom held up until that point.

When Johnston began his walk in recognition of Tubman in 2019, one thing on his mind was how physically taxing it must have been for enslaved people to walk hundreds of miles to freedom. He thought about what they needed to survive the long walk, what the ground must have felt like under their feet, what they saw, and how that differs from what he sees today.

“Through walking you can sometimes feel the desperation of their souls,” he says. “It was just very moving to recognize the issues that they would have encountered — issues of food, clothing, shelter, water — all those things you need in order to function. How far can you go without water? How far can you go without food?”

He began the first 140-mile leg from Poplar Neck, Maryland to Philadelphia over Christmas, spotlighting Tubman’s own Christmas Eve journey to rescue her parents and brothers in 1854. He paused because of the pandemic in 2020 and restarted the second portion on weekends in April of 2021, walking from Philadelphia to Harlem.

In July of this year, he quit his job in human relations to begin the third and final segment of his walk from Harlem to St. Catherines. (He partly funds his journey from donations through his blog.) He arrived in Canada in early September and visited the Salem Chapel where Tubman worshiped. There, he saw the final statue of his journey: a simple bust depicting Tubman’s face outside the church.

As he walked, Johnston listened to a playlist he curated and titled Freedom Songs. Spanning different genres and musical styles, each song connects back to the theme of freedom in some way. Some of his favorites include folksongs by Rhiannon Giddens and You Got To Walk That Lonesome Valley by Mississippi John Hurt.

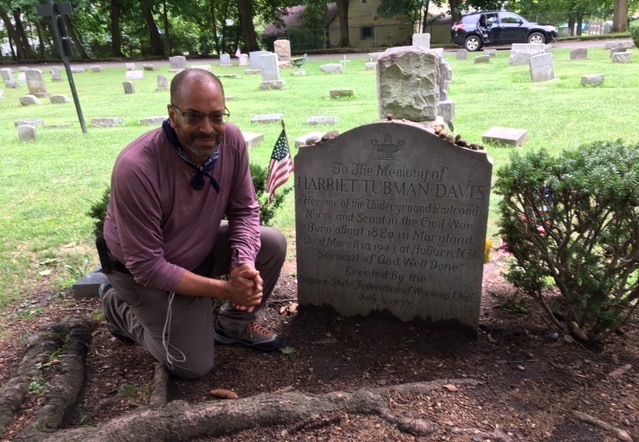

He also made a number of stops. In addition to visiting every Tubman statue along the route, he stopped by her grave in Auburn, New York, and a number of Underground Railroad museums. In Buffalo, he visited a mural painted by his brother, Philadelphia-based artist Keir Johnston, which depicts the word “welcome” in a number of languages. His stop in Albany saw a trip to the Underground Railroad Education Center and a stay at the local Quaker meetinghouse.

When he arrived in Albany, Johnston met with the students at the Underground Railroad Education Center, which was doing a program with the Youth Abolitionist Leadership Institute. Institute cofounder Paul Stewart believes these types of programs help draw attention to history and educate people.

“We were able to have him meet with some of the kids and talk about his experiences and how he was relating his journey to Harriett’s journey,” Stewart says. “[Walkers] call attention to the story, they call attention to it and focus people’s thinking on the drama, the heroism and the ordinariness of the people who did these journeys.”

Why Philly deserves a Harriett Tubman statue

Johnston is already planning his next walks: He hopes to embark on a walk through Underground Railroad stops and historical sites near Gettysburg and Harrisburg and perhaps another walk in Puerto Rico with his brother. While he’s in Philly, he is adding his voice to the conversation about bringing a permanent Tubman memorial to the city.

“Philadelphia was a threshold of freedom, and that story still has not been fully highlighted here,” Johnston says. “I think there’s such a need for that.”

He thinks Tubman is a perfect fit because of her history with Philly — she arrived here in 1849 after escaping slavery, and used a number of Underground Railroad stops in the city to help others, including members of her family, escape.

When Wesley Wofford’s traveling statue of Tubman came to Philly for three months earlier this year, it was met with demands for a permanent monument to the Underground Railroad leader.

The City announced in March that it would be offering a no-bid commission to Wofford, who is based in North Carolina, to design a permanent Tubman statue. Then in August, it reneged. Community advocates were calling for an opportunity for Philly-based artists and artists of color to be able to submit proposals.

In September, the City put out an RFP available to any artist interested in making a statue honoring Tubman, or “another African American’s contribution to our nation’s history.” In other words, the new statue wouldn’t necessarily depict Tubman — despite the fact that her name received the most support when the City put out a survey asking who the statue should depict last month.

Johnston hopes to see Philly honor Tubman with an original monument. He participated in talks led by the City this past spring on whether a memorial should be installed and what it should look like. He plans to continue advocating for the statue in whatever ways he can.

“I think her story is so big here in Philadelphia. It’s larger than life,” Johnston says. “She needs something more.”

![]() MORE ON BLACK HISTORY IN PHILADELPHIA

MORE ON BLACK HISTORY IN PHILADELPHIA