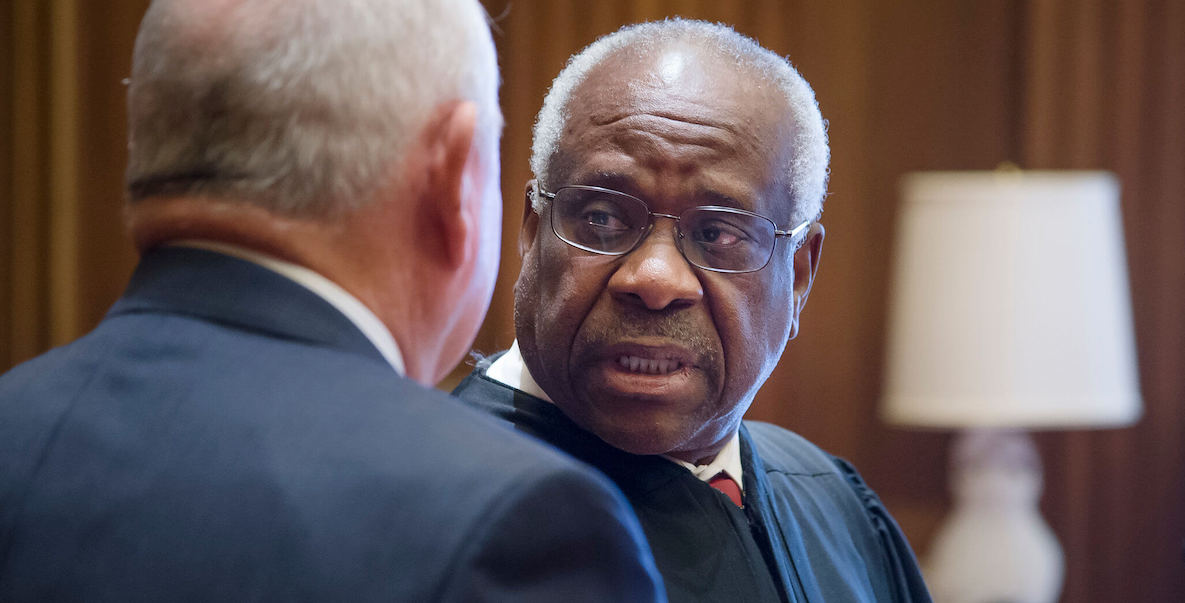

Dear Justice Thomas,

The President has signed your Commission and you have now become the 106th Justice of the United States Supreme Court. I congratulate you on this high honor!

It has been a long time since we talked. I believe it was in 1980 during your first year as a Trustee at Holy Cross College. I was there to receive an honorary degree. You were 31 years old and on the staff of Senator John Danforth. You had not yet started your meteoric climb through the government and federal judicial hierarchy. Much has changed since then.

At first I thought that I should write you privately — the way one normally corresponds with a colleague or friend. I still feel ambivalent about making this letter public but I do so because your appointment is profoundly important to this country and the world, and because all Americans need to understand the issues you will face on the Supreme Court. In short, Justice Thomas, I write this letter as a public record so that this generation can understand the challenges you face as an Associate Justice to the Supreme Court, and the next can evaluate the choices you have made or will make.

The Supreme Court can be a lonely and insular environment. Eight of the present Justices’ lives would not have been very different if the Brown case had never been decided as it was. Four attended Harvard Law School, which did not accept women law students until 1950. Two attended Stanford Law School prior to the time when the first Black matriculated there. None has been called a “nigger” or suffered the acute deprivations of poverty. Justice [Sandra Day] O’Connor is the only other Justice on the Court who at one time was adversely affected by a White male dominated system that often excludes both women and minorities from equal access to the rewards of hard work and talent.

By elevating you to the Supreme Court, President Bush has suddenly vested in you the option to preserve or dilute the gains this country has made in the struggle for equality. This is a grave responsibility indeed. In order to discharge it you will need to recognize what James Baldwin called the “force of history” within you. You will need to recognize that both your public life and your private life reflect this country’s history in the area of racial discrimination and civil rights. And, while much has been said about your admirable determination to overcome terrible obstacles, it is also important to remember how you arrived where you are now, because you did not get there by yourself.

When I think of your appointment to the Supreme Court, I see not only the result of your own ambition, but also the culmination of years of heartbreaking work by thousands who preceded you. I know you may not want to be burdened by the memory of their sacrifices. But I also know that you have no right to forget that history. Your life is very different from what it would have been had these men and women never lived. That is why today I write to you about this country’s history of civil rights lawyers and civil rights organizations; its history of voting rights; and its history of housing and privacy rights. This history has affected your past and present life. And 40 years from now, when your grandchildren and other Americans measure your performance on the Supreme Court, that same history will determine whether you fulfilled your responsibility with the vision and grace of the Justice whose seat you have been appointed to fill: Thurgood Marshall.

I. MEASURES OF GREATNESS OR FAILURE OF SUPREME COURT JUSTICES

In 1977 a group of 100 scholars evaluated the first 100 justices on the Supreme Court. Eight of the justices were categorized as failures, six as below average, 55 as average, 15 as near great and 12 as great. Among those ranked as great were John Marshall, Joseph Story, Roger B. Taney, John M. Harlan, Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr., Charles E. Hughes, Louis D. Brandeis, Harlan F. Stone, Benjamin N. Cardozo, Hugo L. Black, and Felix Frankfurter. Because you have often criticized the Warren Court, you should be interested to know that the list of great jurists on the Supreme Court also included Earl Warren.

You can become an exemplar of fairness and the rational interpretation of the Constitution, or you can become an archetype of inequality and the retrogressive evaluation of human rights.

Even long after the deaths of the Justices that I have named, informed Americans are grateful for the extraordinary wisdom and compassion they brought to their judicial opinions. Each in his own way viewed the Constitution as an instrument for justice. They made us a far better people and this country a far better place. I think that Justices Thurgood Marshall, William J. Brennan, Harry Blackmun, Lewis Powell, and John Paul Stevens will come to be revered by future scholars and future generations with the same gratitude. Over the next four decades you will cast many historic votes on issues that will profoundly affect the quality of life for our citizens for generations to come. You can become an exemplar of fairness and the rational interpretation of the Constitution, or you can become an archetype of inequality and the retrogressive evaluation of human rights. The choice as to whether you will build a decisional record of true greatness or of mere mediocrity is yours.

II. OUR MAJOR SIMILARITY

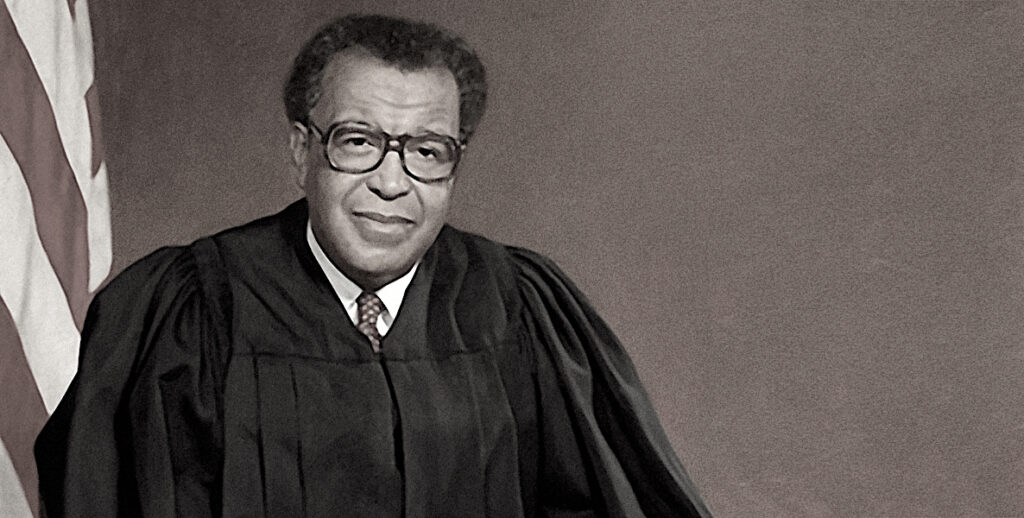

My more than 27 years as a federal judge made me listen with intense interest to the many persons who testified both in favor of and against your nomination. I studied the hearings carefully and afterwards pondered your testimony and the comments others made about you. After reading almost every word of your testimony, I concluded that what you and I have most in common is that we are both graduates of Yale Law School. Though our graduation classes are 22 years apart, we have both benefited from our old Eli connections.

If you had gone to one of the law schools in your home state, Georgia, you probably would not have met Senator John Danforth who, more than 20 years ago, served with me as a member of the Yale Corporation. Dean Guido Calabresi mentioned you to Senator Danforth, who hired you right after graduation from law school and became one of your primary sponsors. If I had not gone to Yale Law School, I would probably not have met Justice Curtis Bok, nor Yale Law School alumni such as Austin Norris, a distinguished Black lawyer, and Richardson Dilworth, a distinguished White lawyer, who became my mentors and gave me my first jobs. Nevertheless, now that you sit on the Supreme Court, there are issues far more important to the welfare of our nation than our Ivy League connections. I trust that you will not be overly impressed with the fact that all of the other Justices are graduates of what laymen would call the nation’s most prestigious law schools.

Black Ivy League alumni in particular should never be too impressed by the educational pedigree of Supreme Court Justices. The most wretched decision ever rendered against Bblack people in the past century was Plessy v. Ferguson. It was written in 1896 by Justice Henry Billings Brown, who had attended both Yale and Harvard Law schools. The opinion was joined by Justice George Shiras, a graduate of Yale Law School, as well as by Chief Justice Melville Fuller and Justice Horace Gray, both alumni of Harvard Law School.

If those four Ivy League alumni on the Supreme Court in 1896 had been as faithful in their interpretation of the Constitution as Justice John Harlan, a graduate of Transylvania, a small law school in Kentucky, then the venal precedent of Plessy v. Ferguson, which established the federal “separate but equal” doctrine and legitimized the worst forms of race discrimination, would not have been the law of our nation for 60 years. The separate but equal doctrine, also known as Jim Crow, created the foundations of separate and unequal allocation of resources, and oppression of the human rights of Blacks.

During your confirmation hearing I heard you refer frequently to your grandparents and your experiences in Georgia. Perhaps now is the time to recognize that if the four Ivy League alumni — all northerners — of the Plessy majority had been as sensitive to the plight of Black people as was Justice John Harlan, a former slaveholder from Kentucky, the American statutes that sanctioned racism might not have been on the books — and many of the racial injustices that your grandfather, Myers Anderson, and my grandfather, Moses Higginbotham, endured would never have occurred.

You can be part of what Chief Justice Warren, Justice Brennan, Justice Blackmun, and Justice Marshall and others have called the evolutionary movement of the Constitution — an evolutionary movement that has benefitted you greatly.

The tragedy with Plessy v. Ferguson is not that the Justices had the “wrong” education, or that they attended the “wrong” law schools. The tragedy is that the Justices had the wrong values, and that these values poisoned this society for decades. Even worse, millions of Blacks today still suffer from the tragic sequelae of Plessy — a case which Chief Justice Rehnquist, Justice Kennedy, and most scholars now say was wrongly decided.

As you sit on the Supreme Court confronting the profound issues that come before you, never be impressed with how bright your colleagues are. You must always focus on what values they bring to the task of interpreting the Constitution. Our Constitution has an unavoidable — though desirable — level of ambiguity, and there are many interstitial spaces which as a justice of the Supreme Court you will have to fill in. To borrow Justice Cardozo’s elegant phrase: “We do not pick our rules of law fully blossomed from the trees.” You and the other Justices cannot avoid putting your imprimatur on a set of values. The dilemma will always be which particular values you choose to sanction in law. You can be part of what Chief Justice Warren, Justice Brennan, Justice Blackmun, and Justice Marshall and others have called the evolutionary movement of the Constitution — an evolutionary movement that has benefitted you greatly.

III. YOUR CRITIQUES OF CIVIL RIGHTS ORGANIZATIONS AND THE SUPREME COURT DURING THE LAST EIGHT YEARS

I have read almost every article you have published, every speech you have given, and virtually every public comment you have made during the past decade. Until your confirmation hearing I could not find one shred of evidence suggesting an insightful understanding on your part on how the evolutionary movement of the Constitution and the work of civil rights organizations have benefitted you. Like Sharon McPhail, the President of the National Bar Association, I kept asking myself: Will the Real Clarence Thomas Stand Up? Like her, I wondered: “Is Clarence Thomas a ‘conservative with a common touch’ as Ruth Marcus refers to him … or the ‘counterfeit hero’ he is accused of being by Haywood Burns … ?”

While you were a presidential appointee for eight years, as Chairman of the Equal Opportunity Commission and as an Assistant Secretary at the Department of Education, you made what I would regard as unwarranted criticisms of civil rights organizations, the Warren Court, and even of Justice Thurgood Marshall. Perhaps these criticisms were motivated by what you perceived to be your political duty to the Reagan and Bush administrations. Now that you have assumed what should be the nonpartisan role of a Supreme Court Justice, I hope you will take time out to carefully evaluate some of these unjustified attacks.

In October 1987, you wrote a letter to the San Diego Union & Tribune criticizing a speech given by Justice Marshall on the 200th anniversary celebration of the Constitution. Justice Marshall had cautioned all Americans not to overlook the momentous events that followed the drafting of that document, and to “seek … a sensitive understanding of the Constitution’s inherent defects, and its promising evolution through 200 years of history.

If there had never been an effective NAACP, isn’t it highly probable that you might still be in Pin Point, Georgia, working as a laborer as some of your relatives did for decades?

Your response dismissed Justice Marshall’s “sensitive understanding” as an “exasperating and incomprehensible … assault on the Bicentennial, the Founding, and the Constitution itself.” Yet, however high and noble the Founders’ intentions may have been, Justice Marshall was correct in believing that the men who gathered in Philadelphia in 1787 “could not have imagined, nor would they have accepted, that the document they were drafting would one day be construed by a Supreme Court to which had been appointed a woman and the descendant of an African slave.”

That, however, was neither an assault on the Constitution nor an indictment of the Founders. Instead, it was simply a recognition that in the midst of the Bicentennial celebration, “[s]ome may more quietly commemorate the suffering, the struggle and sacrifice that has triumphed over much of what was wrong with the original document, and observe the anniversary with hopes not realized and promises not fulfilled.”

Justice Marshall’s comments, much like his judicial philosophy, were grounded in history and were driven by the knowledge that even today, for millions of Americans, there still remain “hopes not realized and promises not fulfilled.” His reminder to the nation that patriotic feelings should not get in the way of thoughtful reflection on this country’s continued struggle for equality was neither new nor misplaced. Twenty-five years earlier, in December 1962, while this country was celebrating the 100th anniversary of the emancipation proclamation, James Baldwin had written to his young nephew:

This is your home, my friend, do not be driven from it; great men have done great things here, and will again, and we can make America what America must become … [But y]ou know, and I know that the country is celebrating one hundred years of freedom one hundred years too soon.

Your response to Justice Marshall’s speech, as well as your criticisms of the Warren court and civil rights organizations, may have been nothing more than your expression of allegiance to the conservatives who made you Chairman of the EEOC, and who have now elevated you to the Supreme Court. But your comments troubled me then and trouble me still because they convey a stunted knowledge of history and an unformed judicial philosophy. Now that you sit on the Supreme Court you must sort matters out for yourself and form your own judicial philosophy, and you must reflect more deeply on legal history than you ever have before. You are no longer privileged to offer flashy one-liners to delight the conservative establishment. Now what you write must inform, not entertain. Now your statements and your votes can shape the destiny of the entire nation.

Notwithstanding the role you have played in the past, I believe you have the intellectual depth to reflect upon and rethink the great issues the Court has confronted in the past and to become truly your own man. But to be your own man the first in the series of questions you must ask yourself is this: Beyond your own admirable personal drive, what were the primary forces or acts of good fortune that made your major achievements possible? This is a hard and difficult question. Let me suggest that you focus on at least four areas: (1) the impact of the work of civil rights lawyers and civil rights organizations on your life; (2) other than having picked a few individuals to be their favorite colored person, what it is that the conservatives of each generation have done that has been of significant benefit to African Americans, women, or other minorities; (3) the impact of the eradication of racial barriers in the voting on your own confirmation; and (4) the impact of civil rights victories in the area of housing and privacy on your personal life.

IV. THE IMPACT OF THE WORK OF CIVIL RIGHTS LAWYERS AND CIVIL RIGHTS ORGANIZATIONS ON YOUR LIFE

During the time when civil rights organizations were challenging the Reagan Administration, I was frankly dismayed by some of your responses to and denigrations of these organizations. In 1984, the Washington Post reported that you had criticized traditional civil rights leaders because, instead of trying to reshape the Administration’s policies, they had gone to the news media to “bitch, bitch, bitch, moan and moan, whine and whine.”

If that is still your assessment of these civil rights organizations or their leaders, I suggest, Justice Thomas, that you should ask yourself every day what would have happened to you if there had never been a Charles Hamilton Houston, a William Henry Hastie, a Thurgood Marshall, and that small cadre of other lawyers associated with them, who laid the groundwork for success in the 20th century racial civil rights cases? Couldn’t they have been similarly charged with, as you phrased it, bitching and moaning and whining when they challenged the racism in the administrations of prior presidents, governors, and public officials? If there had never been an effective NAACP, isn’t it highly probable that you might still be in Pin Point, Georgia, working as a laborer as some of your relatives did for decades?

Even though you had the good fortune to move to Savannah, Georgia, in 1955, would you have been able to get out of Savannah and get a responsible job if decades earlier the NAACP had not been challenging racial injustice throughout America? If the NAACP had not been lobbying, picketing, protesting, and politicking for a 1964 Civil Rights Act, would Monsanto Chemical Company have opened their doors to you in 1977? If Title VII had not been enacted might not American companies still continue to discriminate on the basis of race, gender, and national origin?

The philosophy of civil rights protest evolved out of the fact that Black people were forced to confront this country’s racist institutions without the benefit of equal access to those institutions. For example, in January of 1941, A. Philip Randolph planned a march on Washington, D.C., to protest widespread employment discrimination in the defense industry. In order to avoid the prospect of a demonstration by potentially tens of thousands of Blacks, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt issued Executive Order 8802 barring discrimination in defense industries or government. The order led to the inclusion of anti-discrimination clauses in all government defense contracts and the establishment of the Fair Employment Practices Committee.

Though the Brown decision was issued only six years after your birth, the road to Brown started more than a century earlier.

In 1940, President Roosevelt appointed William Henry Hastie as civilian aide to Secretary of War Henry L. Stimson. Hastie fought tirelessly against discrimination, but when confronted with an unabated program of segregation in all areas of the armed forces, he resigned on January 31, 1943. His visible and dramatic protest sparked the move towards integrating the armed forces, with immediate and far-reaching results in the army air corps.

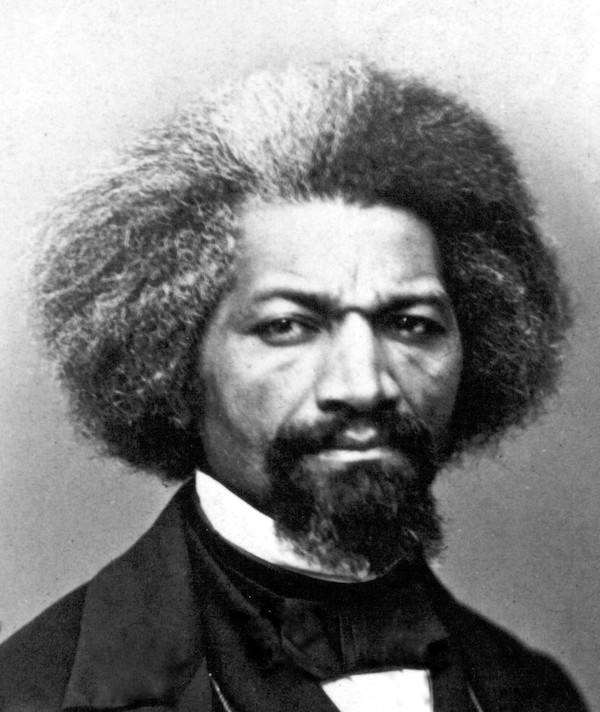

A. Philip Randolph and William Hastie understood — though I wonder if you do — what Frederick Douglass meant when he wrote:

The whole history of the progress of human liberty shows that all concessions yet made to her august claims, have been born of earnest struggle … If there is no struggle there is no progress …

This struggle may be a moral one, or it may be a physical one, and it may be both moral and physical, but it must be a struggle. Power concedes nothing without a demand. It never did and it never will.

The struggles of civil rights organizations and civil rights lawyers have been both moral and physical, and their victories have been neither easy nor sudden. Though the Brown decision was issued only six years after your birth, the road to Brown started more than a century earlier. It started when Prudence Crandall was arrested in Connecticut in 1833 for attempting to provide schooling for colored girls.

It was continued in 1849 when Charles Sumner, a White lawyer and abolitionist, and Benjamin Roberts, a Black lawyer, challenged segregated schools in Boston. It was continued as the NAACP, starting with Charles Hamilton Houston’s suit, Murray v. Pearson, in 1936, challenged Maryland’s policy of excluding Blacks from the University of Maryland Law School.

It was continued in Gaines v. Missouri, when Houston challenged a 1937 decision of the Missouri Supreme Court. The Missouri courts had held that because law schools in the states of Illinois, Iowa, Kansas, and Nebraska accepted Negroes, a 25-year-old Black citizen of Missouri was not being denied his constitutional right to equal protection under the law when he was excluded from the only state supported law school in Missouri.

It was continued in Sweatt v. Painter in 1946, when Heman Marion Sweatt filed suit for admission to the Law School of the University of Texas after his application was rejected solely because he was Black. Rather than admit him, the University postponed the matter for years and put up a separate and unaccredited law school for Blacks.

It was continued in a series of cases against the University of Oklahoma, when, in 1950, in McLaurin v. Oklahoma, G.W. McLaurin, a 68-year-old man, applied to the University of Oklahoma to obtain a Doctorate in education. He had earned his Master’s degree in 1948, and had been teaching at Langston University, the state’s college for Negroes. Yet he was “required to sit apart at … designated desk[s] in an anteroom adjoining the classroom … [and] on the mezzanine floor of the library … and to sit at a designated table and to eat at a different time from the other students in the school cafeteria.”

If you and I had not gotten many of the positive reinforcements that these organizations fought for and that the post-Brown era made possible, probably neither you nor I would be federal judges today.

The significance of the victory in the Brown case cannot be overstated. Brown changed the moral tone of America; by eliminating the legitimization of state-imposed racism it implicitly questioned racism wherever it was used. It created a milieu in which private colleges were forced to recognize their failures in excluding or not welcoming minority students. I submit that even your distinguished undergraduate college, Holy Cross, and Yale University were influenced by the milieu created by Brown and thus became more sensitive to the need to create programs for the recruitment of competent minority students.

In short, isn’t it possible that you might not have gone to Holy Cross if the NAACP and other civil rights organizations, Martin Luther King and the Supreme Court, had not recast the racial mores of America? And if you had not gone to Holy Cross, and instead had gone to some underfunded state college for Negroes in Georgia, would you have been admitted to Yale Law School, and would you have met the alumni who played such a prominent role in maximizing your professional options?

I have cited this litany of NAACP cases because I don’t understand why you appeared so eager to criticize civil rights organizations or their leaders. In the 1980s, Benjamin Hooks and John Jacobs worked just as tirelessly in the cause of civil rights as did their predecessors Walter White, Roy Wilkins, Whitney Young, and Vernon Jordan in the 1950s and 60s. As you now start to adjudicate cases involving civil rights, I hope you will have more judicial integrity than to demean those advocates of the disadvantaged who appear before you. If you and I had not gotten many of the positive reinforcements that these organizations fought for and that the post-Brown era made possible, probably neither you nor I would be federal judges today.

V. WHAT HAVE THE CONSERVATIVES EVER CONTRIBUTED TO AFRICAN AMERICANS?

During the last 10 years, you have often described yourself as a Black conservative. I must confess that, other than their own self-advancement, I am at a loss to understand what it is that the so-called Black conservatives are so anxious to conserve. Now that you no longer have to be outspoken on their behalf, perhaps you will recognize that in the past it was the White “conservatives” who screamed “segregation now, segregation forever!” It was primarily the conservatives who attacked the Warren Court relentlessly because of Brown v. Board of Education and who stood in the way of almost every measure to ensure gender and racial advancement.

I am at a loss to understand what is it that the so-called Black conservatives are so anxious to conserve.

For example, on March 11, 1956, 96 members of Congress, representing 11 southern states, issued the “Southern Manifesto,” in which they declared that the Brown decision was an “unwarranted exercise of power by the Court, contrary to the Constitution.” Ironically, those members of Congress reasoned that the Brown decision was “destroying the amicable relations between the white and negro races,” and that “it had planted hatred and suspicion where there had been heretofore friendship and understanding.” They then pledged to use all lawful means to bring about the reversal of the decision, and praised those states which had declared the intention to resist its implementation.

The Southern Manifesto was more than mere political posturing by Southern Democrats. It was a thinly disguised racist attack on the constitutional and moral foundations of Brown. Where were the conservatives in the 1950s when the cause of equal rights needed every fair-minded voice it could find?

At every turn, the conservatives, either by tacit approbation or by active complicity, tried to derail the struggle for equal rights in this country. In the 1960s, it was the conservatives, including the then-senatorial candidate from Texas, George Bush, the then-Governor from California, Ronald Reagan, and the omnipresent Senator Strom Thurmond, who argued that the 1964 Civil Rights Act was unconstitutional. In fact Senator Thurmond’s 24 hour 18 minute filibuster during Senate deliberations on the 1957 Civil Rights Act set an all-time record. He argued on the floor of the Senate that the provisions of the Act guaranteeing equal access to public accommodations amounted to an enslavement of White people.

If 27 years ago George Bush, Ronald Reagan, and Strom Thurmond had succeeded, there would have been no position for you to fill as Assistant Secretary for Civil Rights in the Department of Education. There would have been no such agency as the Equal Employment Commission for you to chair.

Charles Bowser, a distinguished African American Philadelphia lawyer, said, “I’d be willing to bet … that not one of the senators who voted to confirm Clarence Thomas would hire him as their lawyer.”

Thus, I think now is the time for you to reflect on the evolution of American constitutional and statutory law, as it has affected your personal options and improved the options for so many Americans, particularly non-Whites, women, and the poor. If the conservative agenda of the 1950s, 60s, and 70s had been implemented, what would have been the results of the important Supreme Court cases that now protect your rights and the rights of millions of other Americans who can now no longer be discriminated against because of their race, religion, national origin, or physical disabilities? If, in 1954, the United States Supreme Court had accepted the traditional rationale that so many conservatives then espoused, would the 1896 Plessy v. Ferguson case, which announced the nefarious doctrine of “separate but equal,” and which allowed massive inequalities, still be the law of the land? In short, if the conservatives of the 1950s had had their way, would there ever have been a Brown v. Board of Educationto prohibit state-imposed racial segregation?

VI. THE IMPACT OF ERADICATING RACIAL BARRIERS TO VOTING

Of the 52 senators who voted in favor of your confirmation, some 13 hailed from nine southern states. Some may have voted for you because they agreed with President Bush’s assessment that you were “the best person for the position.” But, candidly, Justice Thomas, I do not believe that you were indeed the most competent person to be on the Supreme Court. Charles Bowser, a distinguished African American Philadelphia lawyer, said, “I’d be willing to bet … that not one of the senators who voted to confirm Clarence Thomas would hire him as their lawyer.”

Thus, realistically, many senators probably did not think that you were the most qualified person available. Rather, they were acting solely as politicians, weighing the potential backlash in their states of the Black vote that favored you for emotional reasons and the conservative White vote that favored you for ideological reasons. The Black voting constituency is important in many states, and today it could make a difference as to whether many senators are or are not reelected. So here, too, you benefited from civil rights progress.

Your success even in your several confirmation votes is directly attributable to the efforts that the “activist” Warren Court and civil rights organizations have made over the decades.

No longer could a United States Senator say what Senator Benjamin Tillman of South Carolina said in anger when President Theodore Roosevelt invited a moderate Negro, Booker T. Washington, to lunch at the White House: “Now that Roosevelt has eaten with that nigger Washington, we shall have to kill a thousand niggers to get them back to their place.” Senator Tillman did not have to fear any retaliation by Blacks because South Carolina and most southern states kept Blacks “in their place” by manipulating the ballot box.

For example, because they did not have to confront the restraints and prohibitions of later Supreme Court cases, the manipulated “white” primary allowed Tillman and other racist senators to profit from the threat of violence to Blacks who voted, and from the disproportionate electoral power given to rural Whites. For years, the NAACP litigated some of the most significant cases attacking racism at the ballot box. That organization almost single-handedly created the foundation for Black political power that led in part to the 1965 Civil Rights Act.

Moreover, if it had not been for the Supreme Court’s opinion in Smith v. Allright, a case which Thurgood Marshall argued, most all the southern senators who voted for you would have been elected in what was once called a “white primary” — a process which preclude Blacks from effective voting in the southern primary election, where the real decisions were made on who would run every hamlet, township, city, county and state. The seminal case of Baker v. Carr, which articulated the concept of one man-one vote, was part of a series of Supreme Court precedents that caused southern senators to recognize that patently racist diatribes could cost them an election. Thus your success even in your several confirmation votes is directly attributable to the efforts that the “activist” Warren Court and civil rights organizations have made over the decades.

VII. HOUSING AND PRIVACY

If you are willing, Justice Thomas, to consider how the history of civil rights in this country has shaped your public life, then imagine for a moment how it has affected your private life. With some reluctance, I make the following comments about housing and marriage because I hope that reflecting on their constitutional implications may raise your consciousness and level of insight about the dangers of excessive intrusion by the state in personal and family relations.

From what I have seen of your house on television scans and in newspaper photos, it is apparent that you live in a comfortable Virginia neighborhood. Thus I start with Holmes’s view that “a page of history is worth a volume of logic.” The history of Virginia’s legislatively and judicially imposed racism should be particularly significant to you now that as a Supreme Court Justice you must determine the limits of a state’s intrusion on family and other matters of privacy.

It is worthwhile pondering what the impact on you would have been if Virginia’s legalized racism had been allowed to continue as a viable constitutional doctrine. In 1912, Virginia enacted a statute giving cities and towns the right to pass ordinances which would divide the city into segregated districts for black and white residents. Segregated districts were designated White or Black depending on the race of the majority of the residents. It became a crime for any Black person to move into and occupy a residence in an area known as a White district. Similarly, it was a crime for any White person to move into a Black district.

If Virginia’s law of 1912 still prevailed, and if your community passed laws like the ordinances of Richmond and Ashland, you would not be able to live in your own house.

Even prior to the Virginia statute of 1912, the cities of Ashland and Richmond had enacted such segregationist statutes. The ordinances also imposed the same segregationist policies on any “place of public assembly.” Apparently schools, churches, and meeting places were defined by the color of their members. Thus, White Christian Virginia wanted to make sure that no Black Christian churches were in their White Christian neighborhoods.

The impact of these statutes can be assessed by reviewing the experiences of two African Americans, John Coleman and Mary Hopkins. Coleman purchased property in Ashland, Virginia in 1911. In many ways he symbolized the American dream of achieving some modest upward mobility by being able to purchase a home earned through initiative and hard work. But shortly after moving to his home, he was arrested for violating Ashland’s segregation ordinance because a majority of the residents in the block were White. Also, in 1911, the City of Richmond prosecuted and convicted a Black woman, Mary S. Hopkins, for moving into a predominantly White block.

Coleman and Hopkins appealed their convictions to the Supreme Court of Virginia which held that the ordinances of Ashland and Richmond did not violate the United States Constitution and that the fines and convictions were valid.

If Virginia’s law of 1912 still prevailed, and if your community passed laws like the ordinances of Richmond and Ashland, you would not be able to live in your own house. Fortunately, the Virginia ordinances and statutes were in effect nullified by a case brought by the NAACP in 1915, where a similar statute of the City of Louisville was declared unconstitutional. But even if your town council had not passed such an ordinance, the developers would in all probability have incorporated racially restrictive covenants in the title deeds to the individual homes.

Thus, had it not been for the vigor of the NAACP’s litigation efforts in a series of persistent attacks against racial covenants you would have been excluded from your own home. Fortunately, in 1948, in Shelley v. Kraemer, a case argued by Thurgood Marshall, the NAACP succeeded in having such racially restrictive covenants declared unconstitutional.

Will you, in your moment of truth, take for granted that the Constitution protects you and your wife against all forms of deliberate state intrusion into family and privacy matters, and protects you even against some forms of discrimination by other private parties … ?

Yet with all of those litigation victories, you still might not have been able to live in your present house because a private developer might have refused to sell you a home solely because you are an African American. Again you would be saved because in 1968 the Supreme Court, in Jones v. Alfred H. Mayer Co., in an opinion by Justice Stewart, held that the 1866 Civil Rights Act precluded such private racial discrimination. It was a relatively close case; the two dissenting justices said that the majority opinion was “ill considered and ill-advised.” It was the values of the majority which made the difference.

And it is your values that will determine the vitality of other civil rights acts for decades to come. Had you overcome all of those barriers to housing and if you and your present wife decided that you wanted to reside in Virginia, you would nonetheless have been violating the Racial Integrity Act of 1924, which the Virginia Supreme Court as late as 1966 said was consistent with the federal constitution because of the overriding state interest in the institution of marriage. Although it was four years after the Brown case, Richard Perry Loving and his wife, Mildred Jeter Loving were convicted in 1958 and originally sentenced to one year in jail because of their interracial marriage. As an act of magnanimity the trial court later suspended the sentences, “‘for a period of 25 years upon the provision that both accused leave Caroline County and the state of Virginia at once and do not return together or at the same time to said county and state for a period of 25 years.'”

The conviction was affirmed by a unanimous Supreme Court of Virginia, though they remanded the case back as to the re-sentencing phase. Incidentally, the Virginia trial judge justified the constitutionality of the prohibition against interracial marriages as follows:

“Almighty God created the races white, black, yellow, Malay and red, and he placed them on separate continents. And but for the interference with his arrangement there would be no cause for such marriages. The fact that he separated the races shows that he did not intend for the races to mix.”

If the Virginia courts had been sustained by the United States Supreme Court in 1966, and if, after your marriage, you and your wife had, like the Lovings, defied the Virginia statute by continuing to live in your present residence, you could have been in the penitentiary today rather than serving as an Associate Justice of the United States Supreme Court.

I note these pages of record from American legal history because they exemplify the tragedy of excessive intrusion on individual and family rights. The only persistent protector of privacy and family rights has been the United States Supreme Court, and such protection has occurred only when a majority of the Justices has possessed a broad vision of human rights. Will you, in your moment of truth, take for granted that the Constitution protects you and your wife against all forms of deliberate state intrusion into family and privacy matters, and protects you even against some forms of discrimination by other private parties such as the real estate developer, but nevertheless find that it does not protect the privacy rights of others, and particularly women, to make similarly highly personal and private decisions?

CONCLUSION

This letter may imply that I am somewhat skeptical as to what your performance will be as a Supreme Court Justice. Candidly, I and many other thoughtful Americans are very concerned about your appointment to the Supreme Court. But I am also sufficiently familiar with the history of the Supreme Court to know that a few of its members (not many) about whom there was substantial skepticism at the time of their appointment became truly outstanding Justices. In that context I think of Justice Hugo Black. I am impressed by the fact that at the very beginning of his illustrious career he articulated his vision of the responsibility of the Supreme Court. In one of his early major opinions he wrote, “courts stand … as havens of refuge for those who might otherwise suffer because they are helpless, weak, out-numbered, or … are nonconforming victims of prejudice and public excitement.”

While there are many other equally important issues that you must consider and on which I have not commented, none will determine your place in history as much as your defense of the weak, the poor, minorities, women, the disabled and the powerless. I trust that you will ponder often the significance of the statement of Justice Blackmun, in a vigorous dissent of two years ago, when he said: “[S]adly … one wonders whether the majority [of the Court] still believes that … race discrimination — or more accurately, race discrimination against nonwhites — is a problem in our society, or even remembers that it ever was.”

You, however, must try to remember that the fundamental problems of the disadvantaged, women, minorities, and the powerless have not all been solved simply because you have “moved on up” from Pin Point, Georgia, to the Supreme Court. In your opening remarks to the Judiciary Committee, you described your life in Pin Point, Georgia, as “far removed in space and time from this room, this day and this moment.” I have written to tell you that your life today, however, should be not far removed from the visions and struggles of Frederick Douglass, Sojourner Truth, Harriet Tubman, Charles Hamilton Houston, A. Philip Randolph, Mary McLeod Bethune, W.E.B. Dubois, Roy Wilkins, Whitney Young, Martin Luther King, Judge William Henry Hastie, Justices Thurgood Marshall, Earl Warren, and William Brennan, as well as the thousands of others who dedicated much of their lives to create the America that made your opportunities possible. I hope you have the strength of character to exemplify those values so that the sacrifices of all these men and women will not have been in vain.

I wonder whether (and how far) the majority of the Supreme Court will continue to retreat from protecting the rights of the poor, women, the disadvantaged, minorities, and the powerless. And if, tragically, a majority of the Court continues to retreat, I wonder whether you, Justice Thomas, an African American, will be part of that majority.

I am 63 years old. In my lifetime I have seen African Americans denied the right to vote, the opportunities to a proper education, to work, and to live where they choose. I have seen and known racial segregation and discrimination. But I have also seen the decision in Brown rendered. I have seen the first African American sit on the Supreme Court. And I have seen brave and courageous people, Black and White, give their lives for the civil rights cause. My memory of them has always been without bitterness or nostalgia.

But today it is sometimes without hope; for I wonder whether their magnificent achievements are in jeopardy. I wonder whether (and how far) the majority of the Supreme Court will continue to retreat from protecting the rights of the poor, women, the disadvantaged, minorities, and the powerless. And if, tragically, a majority of the Court continues to retreat, I wonder whether you, Justice Thomas, an African American, will be part of that majority.

No one would be happier than I if the record you will establish on the Supreme Court in years to come demonstrates that my apprehensions were unfounded. You were born into injustice, tempered by the hard reality of what it means to be poor and Black in America, and especially to be poor because you are Black. You have found a door newly cracked open and you have escaped. I trust you shall not forget that many who preceded you and many who follow you have found, and will find, the door of equal opportunity slammed in their faces through no fault of their own. And I also know that time and the tides of history often call out of men and women qualities that even they did not know lay within them. And so, with hope to balance my apprehensions, I wish you well as a thoughtful and worthy successor to Justice Marshall in the ever ongoing struggle to assure equal justice under law for all persons.

Sincerely,

Judge Higginbotham first published this piece in the Penn Law Journal in 1991, with 85 footnotes. See the original here.

Header photo: USDA via Flickr