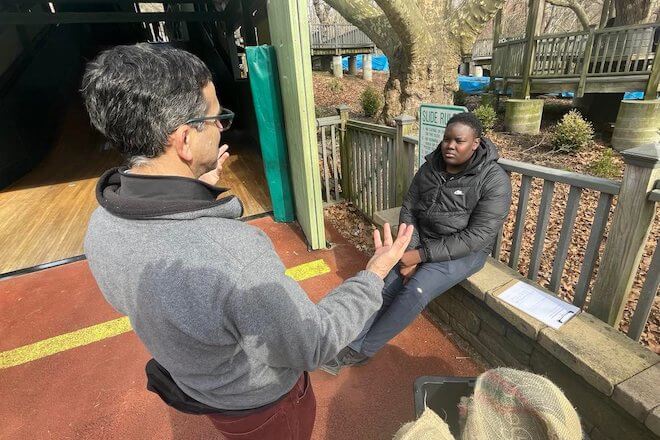

Smith Memorial Playground in Fairmount Park isn’t a place most Philadelphia high school teachers would think of as an everyday classroom. But Michael Friedman of Belmont Charter High School is not your typical high school teacher. To Friedman, the playful green landscape is the perfect spot for lessons on the environment. Friedman teaches a class founded on the philosophy of place-based learning.

On a recent Wednesday, 15 of Friedman’s students rode SEPTA to Smith. Once there, the 11th graders learned about and offered suggestions on improving the site’s environment. It was a day of wonder, science, imagination — and a giant wooden slide. And, although it was a lot like these students’ school year so far, it was still unlike most every other class these kids — or any Philadelphia public or charter school students — had taken before.

Environmentalist and impact investor Laurie Lane-Zucker and Middlebury College English professor John Elder came up with the idea of taking students outside their classrooms as part of a learning curriculum more than 30 years ago. Elder and Lane-Zucker believed group study outside school could directly link to and enhance traditional subjects like English, history, and math.

Philly educators like Faustman and Friedman believe students of privilege shouldn’t be the only ones to benefit from place-based learning.

Belmont Charter Network CEO Jennifer Faustman agrees. Her school felt students at risk of dropping out or failing would especially benefit from place-based education, and that the curriculum would connect them more to their coursework, their instructor, each other, and their community. Although the program is still too new to judge, so far, students and teachers agree: It’s been successful.

“We feel passionately about reaching kids that are sort of turned off from the traditional classroom environment,” Faustman says. “We think a different, more culturally responsive approach would get them more involved and more invested in their learning,”

Modeling success in the suburbs

Radnor Township adopted a place-based learning curriculum 20 years ago. According to its website, Radnor school district’s middle and high school educators “use a rigorously paced approach that combines social studies and English with above-grade and college-level materials.” Radnor’s place-based learning students “are to be proactive, both in assignment completion and in the continued development of skills and intellectual inquiry.”

Radnor is technically only a few miles from Belmont, but socio-economically, it’s worlds away. The suburban high school’s enrollment is 69.7 percent White. Belmont’s enrollment is over 90 percent Black. The median household income for Radnor Township is $139,076. In Parkside, it’s $39,923. And yet, although its neighborhood’s poverty and homeless student rates are some of the highest in the city, Belmont High School’s four-year graduation rate of 94.6 percent, is not so far from Radnor’s 98.7 percent. Both surpass the state average of 86.7 percent.

There are key areas where Belmont is struggling, though, like attendance, career standards and not reaching benchmarks in English Language Arts, math and science on the most recent Pennsylvania State Assessments, or PSSA, according to the state’s Department of Education.

Faustman spent a day at Radnor, evaluating their program.“It was just really cool to see kids leading the conversation and really going deep on a subject,” she says.

Bringing place-based learning to Belmont

Philly educators like Faustman and Friedman believe students of privilege shouldn’t be the only ones to benefit from place-based learning. They believe the concept can enhance the education of Philadelphia students from struggling neighborhoods — and get them involved in the sustainability of their community.

So, a few years ago, Belmont Charter Network applied for and — not without a few raised eyebrows — the state’s first “innovation school” designation and funding to go with it. Belmont used these funds, in part, to create place-based classes they call STRIPES, for STudying, Real, Issues, Places and Experiences.

STRIPES carves out three pathways of learning for students: self knowledge, authentic partnerships and integrated learning. “We want kids to be able to know themselves in their place and be empowered to take action,” says Friedman.

The new program has gone through a few iterations, especially over Covid. This year, the for-credit elective is available to 11th graders only; 17 percent of Belmont’s junior class is enrolled.

For the first three weeks of the school year, students create relationships with each other while performing an overview of the neighborhood.

The program follows a sequence of steps, beginning with exploring who the students and their supporters are. In this session the students discuss their hopes, dreams and goals with their teacher. The next step is for students to declare what they want. This is where students fill out STRIPES’ social contract.

“They don’t all have to love it, but they have to be able to live with it. And so our social contract this year has five agreements: Strive to be proactively amazing; be a team player; be supportive; be open to growth; and be who you are,” says the teacher.

For the first three weeks of the school year, students create relationships with each other while performing an overview of the neighborhood. Then, the class does case studies of people and places in the area. So, it follows a format, but, says Belmont junior Ibrahim Maharaja, “In STRIPES there really is no typical week.”

He continues, “On Mondays, we read articles and do background research and come up with questions, and then we set goals for ourselves to accomplish. On Tuesdays, we’ll go visit a site, answer our questions. On Wednesdays, we’re back in the classroom where more research is done. On Thursday, we go back outside and offer help where needed in the community. On Friday, we reflect on our goals and dedication project in which we had a choice of how to share our learning. This could be an article, a blog post, or a crossword puzzle.”

STRIPES director Virginia Friedman says adjusting to place-based coursework usually takes time. “It can be a little scary transitioning into this style of learning. There’s often a honeymoon period where it seems really exciting. And then it’s like, Oh man, we’re going outside again? So, there are structured pieces of it. When we go out to sites, the kids know that they have notes that they’re going to be generating questions that they will answer.”

More than halfway into the year, “This experience has provided me with a new perspective in how people can absorb information in an outdoor space rather than a traditional classroom,” says Maharaja.

Junaid Castillo, another Belmont 11th grader, says in most classrooms he’s been in, the connection between teacher and student is broken; students tend to disengage. But, “by doing this, the students are more active on what’s been taught to them.”

Forming community bonds

Community itself helps shape STRIPES’ curriculum. For example, Friedman met Tashia Rayon of Centennial Parkside CDC and the Black Urban Theater through Michael Burch, founder and editor of The Parkside Journal. Burch believes engaging students in the neighborhood is a win-win. “There are opportunities here that many young people, especially young African American students, may not be thinking of,” he says.

Friedman, Burch and Rayon crafted a two-day agenda for students at the theater, which is a space for neighborhood performance and visual arts. After icebreakers and getting to know the environment, the students broke into groups to write what they’d like to see for the theater. “Some of them wrote how they would like the Black Urban Theater to look aesthetically and how they would go about doing that,” says Rayon.

The partnership resulted in the 555 Program, an internship with a stipend in which five students work at the theater for five months, then receive $500 each. They also receive referrals and a certificate of completion. Their job: Help engage more young people in the venue’s programs.

“I saw the future in those students. I saw Colin Powell. I saw Michelle Obama. And I would call them those names,” says Tashia Rayon.

This is another way STRIPES works: It can transform a one-time class into long-term relationships. As students worked with Rayon, their personalities shined, she says. “I saw the future in those students. I saw Colin Powell. I saw Michelle Obama. And I would call them those names.”

Other community partners that work with the Belmont STRIPES program include: LandHealth Institute, Youth Volunteer Corps of Philadelphia, PHS’s Viola Street Community Garden, We Love Philly, and Plant and People.

Steve Jones of LandHealth has been a partner for two years. “A big part of what we do is what you could call ecological education for people of all ages and all situations,” he says, “Our approach to education is experiential. So it’s a really good fit between our two missions.”

The future of STRIPES

To evaluate their high school place-based learning program, Belmont Charter Network brought on Marta Biarnes, founder and CEO of STEMSpark, a Philadelphia-based science education and consulting company. Biarnes found STRIPES students were more willing to act within the classroom and within the community, and felt their voices were heard more than in a traditional learning setting.

“Going out in the community and meeting with different business owners or stakeholders or community members does increase the possibilities that [students] see for their future selves,” Biarnes says. “This idea of self-knowledge increases. They are better able to find what they might want to do in the future because of the intensive support that they receive.”

Although the program’s long-term benefits can’t be measured quite yet, Faustman says she and her colleagues have seen immediate effects. “Students become more engaged in their other subjects at school, and they take on projects that connect them to the community, and connect them to the class — that is really where you see kids thriving.”

The team at Belmont would like the place-based learning program to continue and to expand. They are looking for opportunities to replicate STRIPES to a second classroom next year and possibly middle school. They also plan to propose a 12th-grade curriculum where seniors get credit for an English class and an elective, and receive internship opportunities.

But, like too much in education, it’s likely a question of money. Although Faustman won’t say how long the funds for the program will last, Friedman worries.

“How are they going to continue to fund [STRIPES] after the grant runs out?” he says. “That’s the question we’re going to be answering over the next couple of years.”

Faustman reiterates that her students deserve the same level of educational experience Main Line students receive. “[Radnor] saw that they wanted something richer for their students,” she says. “We feel passionately about reaching kids that are turned off from the traditional classroom environment. We think a different approach will get [Belmont students] more involved, more invested in their learning.”

![]() MORE ON EDUCATION FROM THE CITIZEN

MORE ON EDUCATION FROM THE CITIZEN