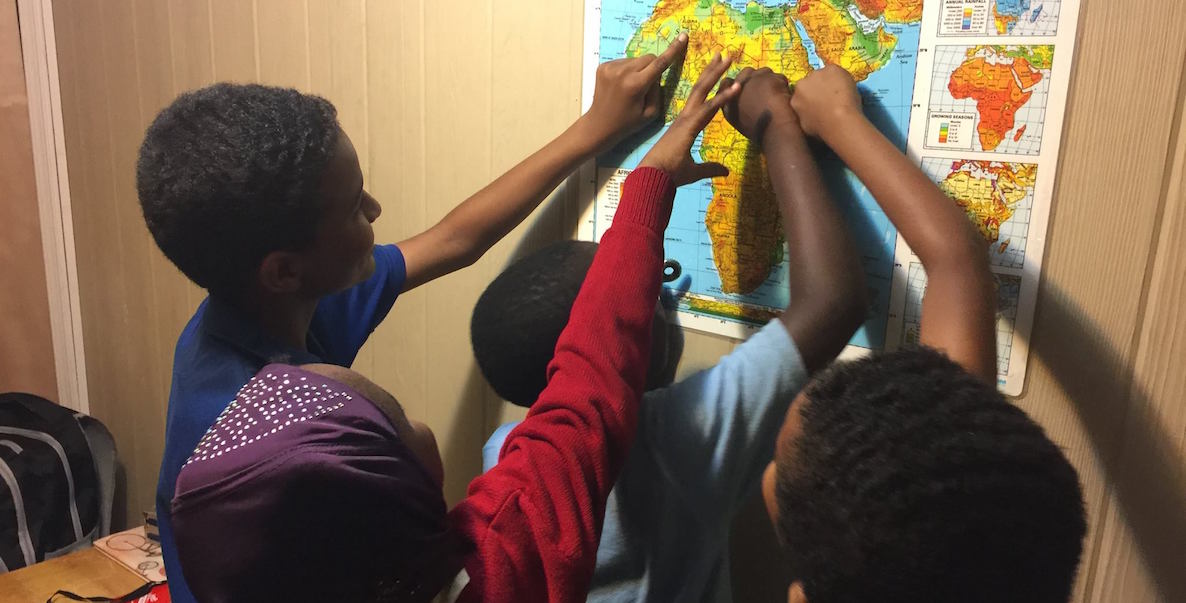

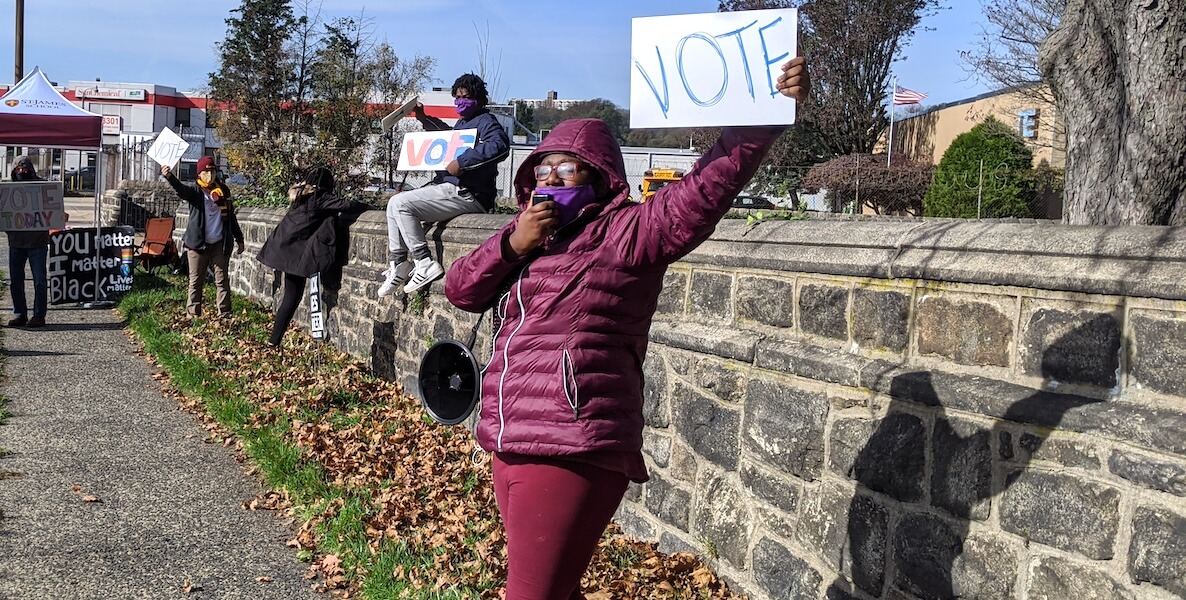

Look at those beautiful children! Socially distanced. Coats on against the chill. Lined up and climbing to sit astride the wall that runs around their church—the church that old, white parishioners tried to wrestle away from the Episcopal Diocese of Pennsylvania all for themselves , and lost in the early 2000s.

Listen to youthDo Something

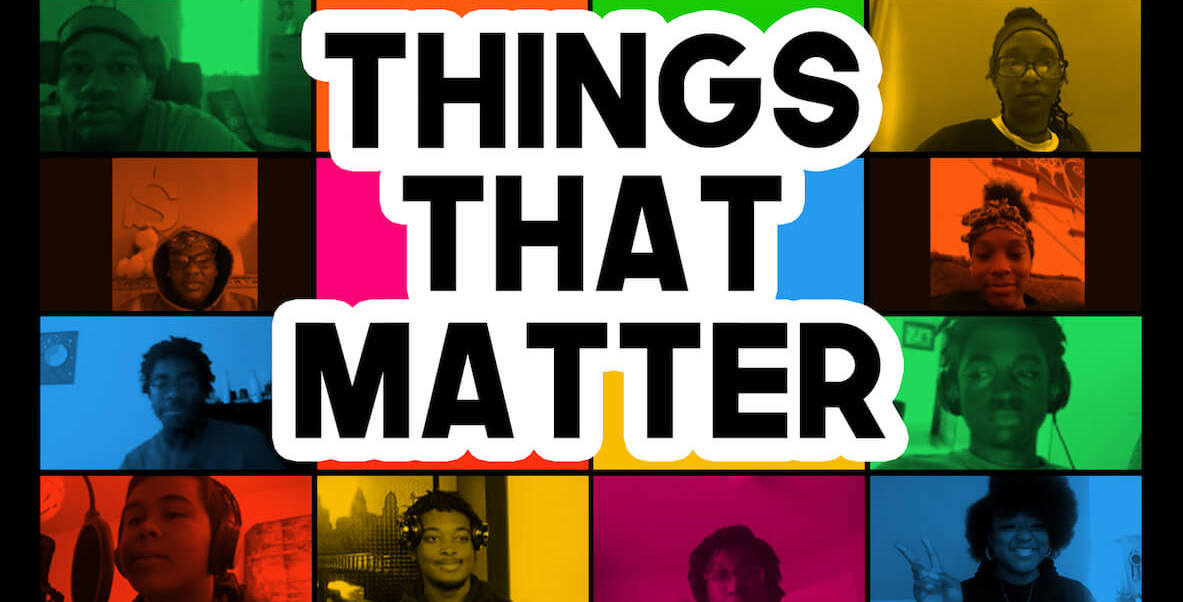

St. James’ new director of choral music and art/music education, Javvieaus Stewart, has been teaching a unit on hip-hop that underscores the connections. The school newsletter reports that she “started with the four basic elements of hip-hop: graffiti art, breakdancing, DJing and rapping.”

I couldn’t help but think of the curriculum by Dr. Decoteau Irby we commissioned at Art Sanctuary, a Black arts organization I founded in 1998, now coming to shelter under the wing of the African American Museum in Philadelphia.

Do The Knowledge Learning Guide remains an excellent guide for teachers — and a refreshment in the classroom. Like Ms. Stewart’s middle school class, it begins with the four elements of hip-hop and connects them to ways Black culture conveys knowledge.

Art Sanctuary’s after-school students loved it. Teaching spoken word through that curriculum led to a “hip h’opera” song cycle in partnership with Opera Philadelphia, which laid a foundation for their stunning 2017 opera, We Shall Not Be Moved.

And what does that culture teach us, in its percussive wisdom? Inside, at the core of hip-hop, is joyous storytelling and word-play made more emotionally powerful by an infinite variety of beats. Hip-hop makes meaning from the found objects of Black Lives. Even in its usually male, seemingly individualistic lyrics, the Black cultural foundation of hip-hop encourages resilience. It assumes that political critique will pivot directly toward action for justice. So Ms. Stewart introduces them to old-school and “conscious” hip-hop, including Tupac, whose album “Me Against the World” links through to When We All Vote, including these famous lyrics:

Always do your best, don’t let this pressure make you panic / And when you get stranded / And things don’t go the way you planned it / Dreamin’ of riches, in a position of makin’ a difference / Politicians are hypocrites, they don’t wanna listen.

But they will listen, politicians, that is.

TAKE ACTIONWhite people,

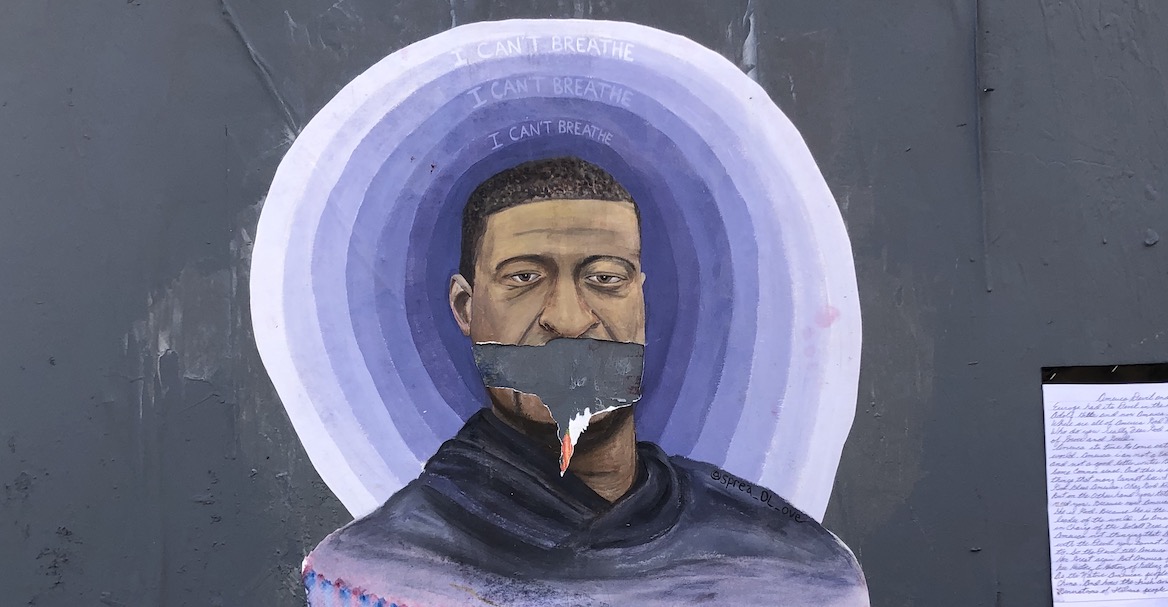

Black Lives already know everything America is ashamed of. Kids too young to vote know it. They accept that we’ve got to live together. What’s non-negotiable, because it is as true as the precious gift of consciousness, is that Black Lives Matter.

Even in its usually male, seemingly individualistic lyrics, the Black cultural foundation of hip-hop encourages resilience. It assumes that political critique will pivot directly toward action for justice.

Because conditions necessary for Black Lives sustain us all. If Black Lives Matter, really matter, then we’ll begin to grieve together for slavery. When Black Lives Matter, America can look through the Eye of Providence on our greenbacks and create measures for the imprint of separated families and sacrificed lives on our wealth. And if we were to know that, feel it, wonder and think and pray about how to make some amends toward the karmic debt of Black Lives Wasted, still wasting, today, well then, maybe the scales would drop from American eyes. Then we could never sanction the United States taking children from healthy, competent parents who love them enough to carry them 1,000 miles thinking they’d escape the worst harm they could imagine.

Think of the weight of shame that would be lifted from our unloved and unloving electorate. Tubman said it, and Frederick Douglass, and so many more in so many ways. These children have written it onto their sign, God bless them. Look, all the way at the back of the photo:

You matter. I matter. LGBTQ rainbow-flag Lives Matter. Black Lives Matter.

Lorene Cary is a lecturer at Penn and author, most recently of Ladysitting: My Year with Nana at the End of Her Century, a care-taking memoir, and My General Tubman, a play about the complex journey of the abolitionist/activist that ran this year at Arden Theatre. She is the founder of #Vote That Jawn, the initiative to register and engage young voters.

Photo courtesy St. James School