A large majority of residents living near Washington Avenue in South Philadelphia have told the City’s Office of Transportation that they want the Kenney administration and City Council to prioritize the safest possible redesign option for pedestrians there when the street is repaved and restriped next year.

Washington Avenue is statistically one of South Philadelphia’s most dangerous streets for pedestrians, and the City has had a goal of repaving and restriping it to be safer since around 2012. But the city’s governing institutions have failed to deliver a safer Washington Ave. for the entire last decade for reasons that are emblematic of some larger problems with the City’s approach to planning governance across a whole range of issues.

The upshot of Councilmanic Prerogative over streets policy has been almost entirely negative from the perspective of safety, air quality, transit, and the city’s goals for climate and transportation mode-shift.

The first process around Washington Avenue started in 2012 very similarly, with a plan that went through an official public engagement process, only to be vocally opposed at the very last minute by a group of mostly 9th Street area business owners. That led to a series of unofficial City Council-led public meetings that were quite heated, and the Nutter administration subsequently abandoned that attempt.

Then for a few years nobody tried to make anything happen until around 2019 when the need to finally repave Washington became more dire.

Where things stand in February of 2022 is that the City’s Office of Transportation is now on the 5-yard line for their second try at restriping Washington Avenue. Multiple surveys have borne out the same finding again and again: Neighbors really value pedestrian safety over traffic speeds.

Unfortunately, decision-makers decided last weekend not to deliver the result that the majority wants, as a result of some rearguard attacks on the process from a handful of politically connected insiders and businesses who have been lobbying councilmembers Kenyatta Johnson (who is facing a federal corruption trial this year) and Mark Squilla against the plan—but never demonstrating that anything close to majority opposition exists.

Over 5,000 people—more than 71 percent of the original survey-takers—indicated in the City’s own survey that they wanted the safest three-lane option possible. In addition, a majority of the area neighborhood associations, almost all school community groups and principals whose school catchments touch Washington, and the 2nd Ward Democrats vocally support the original Kenney plan. So how is it that the political system could produce a decision so out of touch with what most people want?

While there’s obviously a lot of blame to share among councilmembers Squilla and Johnson, with the largest portion belonging to the Mayor’s Office of Transportation, Infrastructure, and Sustainability (OTIS), there’s a very important culprit who hasn’t been named in the many good articles and pieces of commentary that have since been published about the situation: former Councilmember Bill Greenlee.

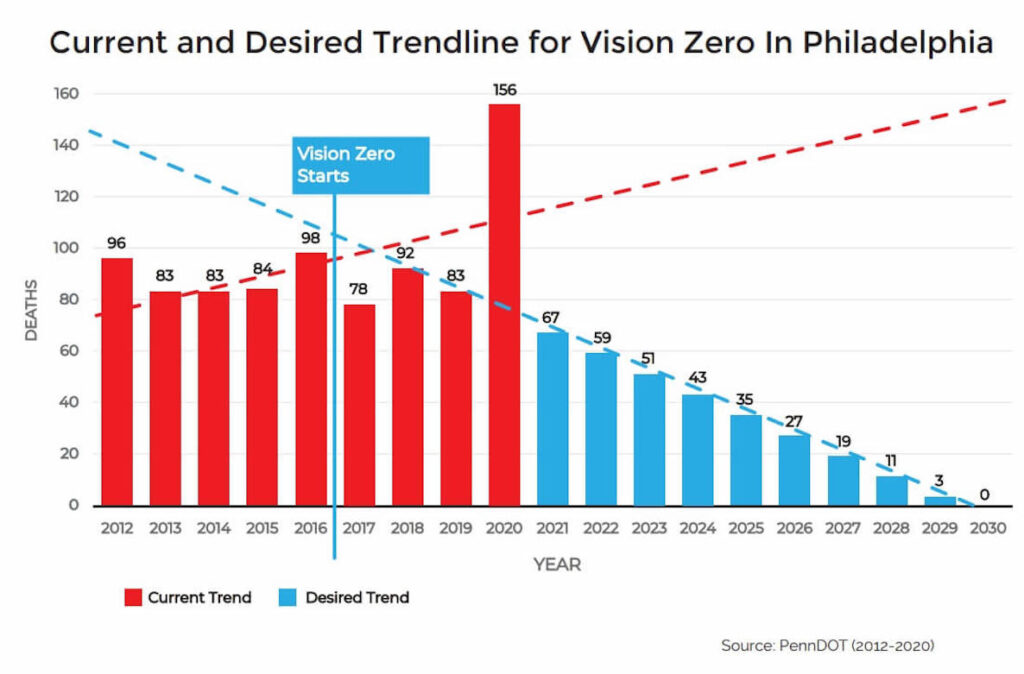

As we’ve written before, the City’s pathetic progress toward Vision Zero—the Kenney administration’s initiative to reduce traffic deaths and serious injuries to zero by 2030—is primarily a governance failure, and former Councilmember Greenlee is the father of that governance failure.

Back in 2012, then-Councilmember Greenlee led the backlash on the Nutter administration’s decision to pilot buffered bike lanes on Spruce, Pine, 10th and 13th streets, introducing a bill that would have given City Council sole discretion over all street-design changes—a power reserved only for the Streets Department up until then.

That bill got bargained down a bit to the point where City Council ordinances would only be required to approve street changes in cases where a travel lane or a parking lane would be replaced with a bike lane.

They essentially gave themselves that power in order to never use it, and the last 10 years of experience with this law have borne this out. In only two or three very limited situations has this happened at all since 2012.

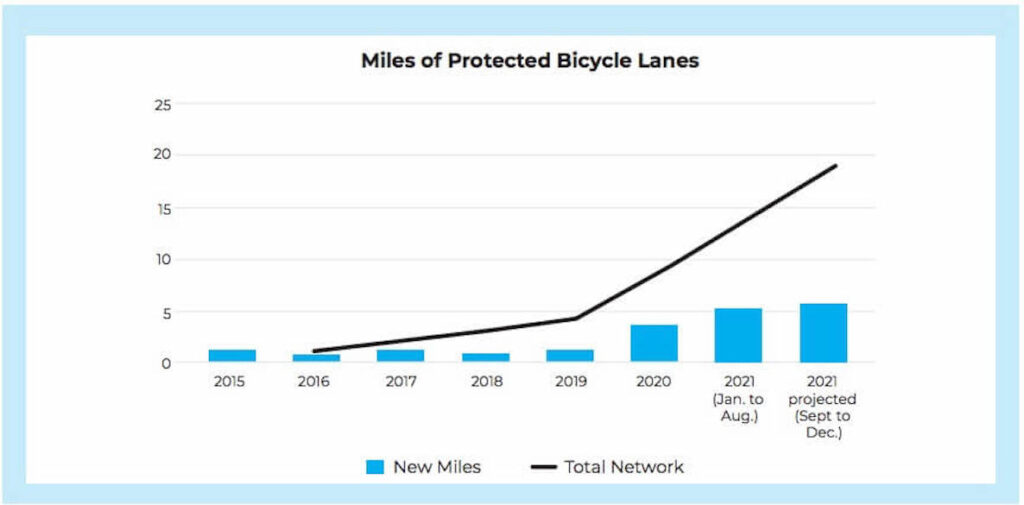

After that law passed, new bike lane creation stalled out and never recovered, despite some big promises from the Kenney administration about striping 40 new miles of protected bike lanes by the end of his second term.

So Greenlee and fellow travelers got exactly what they wanted, which was a much-reduced velocity of Complete Streets activity from two successive mayoral administrations, with some very dark unintended consequences for the human lives needlessly lost on city streets since then.

What’s most insidious about this law isn’t just the straightforward effect, but also the normative expectations it’s created, and the implied threat of further action by Council if the mayor ever chooses to use the powers the office still has without letting district councilmembers drive the process.

That’s perhaps the most obnoxious thing about the Kenney administration’s approach to Washington Avenue, where—according to a Law Department opinion obtained by state Senator Nikil Saval’s staff—there isn’t a City Council ordinance required for the administration to pass the original three-lane plan that they’d initially announced as their final design decision. City Council only enters the fray officially because their votes are needed to pass some accompanying parking and loading regulations needed to make the street redesign changes work.

But what keeps happening is that, even in situations where there isn’t councilmanic prerogative over street changes, the Kenney administration still treats this as a norm, and they don’t ever try and press their advantage even when they have the power. And that’s all because of the ever-present but unspoken assumption that if they did, City Council would go back and take the rest of their power away.

That’s not an unfounded strategic judgment from OTIS or the administration exactly, but it’s also hard to see how that strategy of yielding to district councilmembers has actually produced any good results, anywhere. The projects that do happen are usually watered down quite a bit due to Council involvement, and it’s impossible to measure all the projects that are never proposed in the first place because of the calculation that Council members would never go for them.

In the case of Washington Avenue, the Kenney administration’s decision to play along with the idea that the need for a parking regulation ordinance to accompany their plan gives councilmembers any leverage has been an albatross around the neck of this project the entire time. It’s also allowed Council to shape the project for the worse while obscuring their influence from public view.

When members of the public wrote to councilmembers Squilla and Johnson to express support for the original final design decision, the members wrote back that they were waiting for OTIS to release a final, final plan and didn’t want to pre-judge. But then behind the scenes, according to sources, those same members were allegedly telling OTIS not to recommend the most popular option. What everybody seemingly wanted was for a watered-down plan to simply materialize out of nowhere, without any elected decision-makers having to be seen supporting or opposing it.

The upshot of councilmanic prerogative over streets policy in the decade since the Greenlee bill passed has been almost entirely negative from the perspective of safety, air quality, transit—and the City’s goals for mode-shifting on climate and transportation. But it’s gone mostly unnoticed as the main institutional driver of these dysfunctional politics. Unfortunately, undoing this system will require electing some very different City Council people in 2023 and beyond who are committed to undoing this public safety disaster of a policy.

Jon Geeting is the director of engagement at Philadelphia 3.0, a political action committee that supports efforts to reform and modernize City Hall. This is part of a series of articles running on both The Citizen and 3.0’s blog.

![]()

RELATED

Ideas We Should Steal Revisited: Reduce Covid Risk By Walking

Header photo courtesy Phila. Bikes / Flickr