At a time when they should be looking inward, local Dems are (predictably) gathering in a circular firing squad. Longtime party boss Bob Brady, some traditional pols, and progressives have engaged in post-mortem finger-pointing.

Brady complained that the “elitist” Harris campaign didn’t engage him or his 3,000-strong army of committee people — and didn’t cough up enough walking around money for them to make a difference on Election Day. Kamala Harris’s senior advisor in the state, Brendan McPhillips, responded with a no-holds-barred Inquirer op-ed. Brady’s operation, he wrote, “resemble[s] more of a social club for political has-beens than a functioning organization designed to grow and build power for working people.”

In short order, the Working Families Party joined the progressive attack line, as did respected longtime politico Terry Gillen: “It’s time for the party to think about bringing in new leadership and transitioning to new people who have a better feel for how to increase turnout,” she told The Inquirer. “[Brady] seems to not feel like there’s a problem. That suggests that he’s not sure how to handle this.” (To her credit, long before this election, Gillen has been highlighting the lackadaisical nature of Philly Dems’ backroom ways, as in this 2018 piece for The Citizen.)

Like Gillen, I’m a critic of machine politics, as Brady knows — which is why every time I see him, he begins just about every sentence by saying, “I know you always kick the shit out of me in that newspaper of yours.” Political machines are inherently anti-democratic; they work for those inside of them, but the common good can often fall by the wayside.

As even Brady would concede, machine-driven “ground game” turnout operations don’t really determine presidential election outcomes. Messaging does.

That’s a lesson Abner Mikva, a hero of democracy, learned in 1948 when, at 22, he naively wandered into a Chicago ward office seeking to help support Democratic presidential Adlai Stevenson in that year’s election. “Who sent ya?” he was promptly asked. When he explained he was just a committed citizen looking to volunteer, he was dismissed with a wave of the hand: “We don’t want nobody that nobody sent.”

It’s that type of insularity — particularly in a town like Philly, where the party in charge has long used the crumbs of patronage to appease its tacit opposition — that depresses robust civic participation. As a congressman, judge and mentor to some skinny dude named Obama, Mikva went on to wage a career against government for and by the merely connected.

It’s not about the machine

That said, sometimes machines do inure to the public good. Machine politics has catapulted generations of Philadelphians — mostly White ethnics — into middle-class lives. And, politically, particularly in low turnout elections, machines are adept at seizing and maintaining public office.

Which is why the debate over Brady and his (fading?) machine is precisely the wrong conversation to be having in the aftermath of this presidential election. First, it conveniently lets progressive operatives like McPhillips off the hook. Nowhere in his oped did McPhillips — who was coming fresh off of Helen Gym’s disappointing performance in last year’s mayoral race — take any accountability for Harris’s loss, with its massive misreading of the cultural zeitgeist.

Second, a bit of background. Starting with Obama’s 2008 campaign, presidential campaigns began sweeping into cities and running things themselves — not relying so much on the locals. Back then, Brady convened Obama’s team of outsiders and his ward and committee people for a mega sit-down. As recounted by eyewitness Zack Stalberg, then head of the political reform group Committee of 70 who’d been asked by Brady to address the crowd on the importance of ethics during campaign season, Brady made it clear to Obama’s fresh-faced Ivy League grads that he expected “his people” to be “respected” while they went about their business in his city. But he also walked around holding a baseball bat — yeah, Capone-like — while warning his charges that they were, in turn, to cooperate with the Obamaites.

As the brilliant 20th Century ad man George Lois liked to say, “You have to have an idea” before you have something to sell, and Clinton circa 1994 just might offer a contemporary case study.

Part of Brady’s complaint this go-around — in addition to the “elitism” of the Harris campaign, save operative Kellan White — is that no such Five Families-like sit-down took place. There may be a whiff of extortion to it, but when you shell out bucks to the City Committee, part of what you get, if you’re sophisticated, is Brady holding a baseball bat while “urging” his foot soldiers to cooperate with you. The Obamaites knew, at least, that it couldn’t hurt.

After all, as even Brady would concede, machine-driven “ground game” turnout operations don’t really determine presidential election outcomes. Messaging does. Think of it: McPhillips boasted of “knocking on 2 million doors” the last weekend of the campaign, which, he posited, was 2 million more than Brady’s team. I heard ad nauseam how determinative it would be that the Harris campaign had headquarters in 50 of the Commonwealth’s 67 counties. Turns out, it doesn’t matter how many salesmen you have if your customer ain’t buying what you’re selling.

Arguing over who knocked on more doors in 2024 — while Trump reached more folks by seizing on the growing cultural impact of podcasters like Joe Rogan and Theo Von — is to advertise the increasing obsolescence of progressive and party boss alike.

The jig is up on the ground game canard. Don’t believe me? Check out this mea culpa from one of its progenitors, the Republican-turned-Never Trump consultant Mike Murphy. “The most overrated thing that is 90 percent bullshit in a general election, that I’ve always believed but I don’t say a lot, is ground game,” he said on the Hacks on Tap podcast with David Axelrod. “A lot of wasted horseshit money that makes a very marginal thing. Now, in a low turnout election? Different story. I just hate the ROI of paying people to talk to other people who are already voting for you.”

It’s the messaging, stupid.

Learning from a playbook that … worked

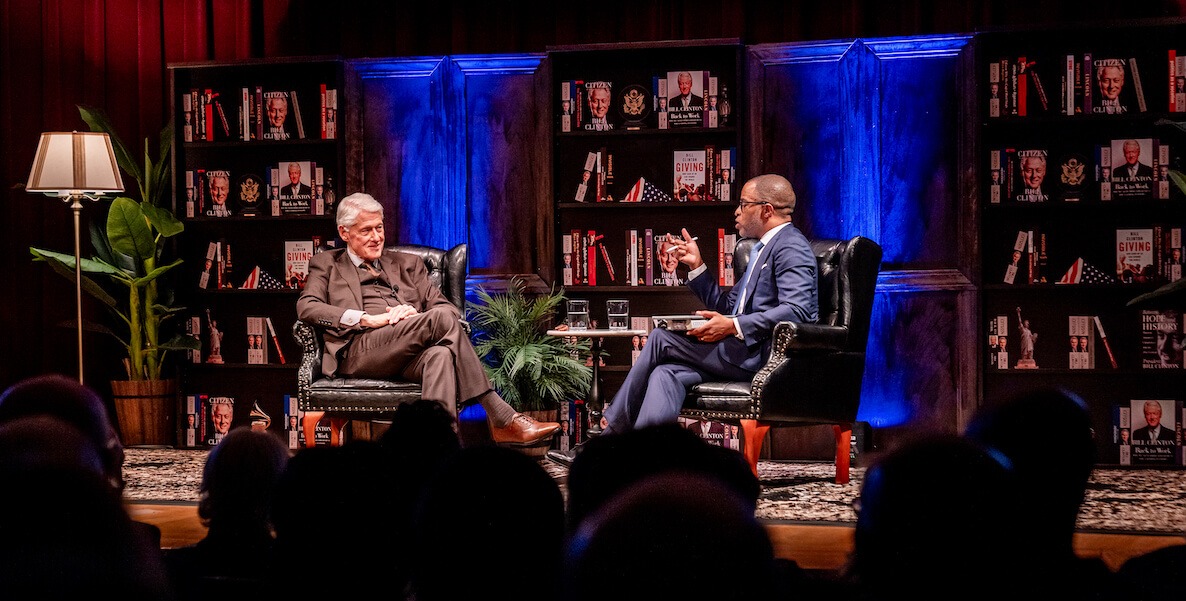

Which brings us to Wednesday night this week, and former President Bill Clinton’s visit to the Free Library to promote his new book, Citizen: My Life After The White House. The voice is raspier now, the hands not quite so steady. He’s pushing 80, but talk about your forever fertile minds. He spoke of trying to learn something new each day — he’s gotten deep into astrophysics! — and his analysis of these times was just what his rapt audience needed to hear. He laughed at how much fun he had stumping for Harris at the Georgia State Fair, posing for photos and sharing laughs with a bunch of guys in red MAGA hats.

“If you scratch long enough, eventually you’ll find a human being there,” he said. “We’ve gotta talk to people.”

As the brilliant 20th-century ad man George Lois liked to say, “You have to have an idea” before you have something to sell, and Clinton circa 1994 just might offer a contemporary case study. After the 12-year cultural realignment of the Reagan Revolution, Dems were in the political wilderness, widely seen as captive to special interests — the common good be damned. Clinton and the Democratic Leadership Council (which Jesse Jackson derided as the Democratic Leisure Council) reshaped Democratic politics, seeking progressive ends through communitarian means.

Today, it’s worth learning from the type of introspection Clinton modeled for Democrats back then. If ever there was a time for regrouping, it’s now. Did you see the results of the Blueprint survey, which polled the last weeks of the election? More comprehensive than any exit poll out there, it goes deep on just why Harris lost: inflation, immigration, and too much focus on cultural issues like land acknowledgments and pronouns in place of concrete actions to help the middle class.

Ah, yes, the middle class. When Brady calls Harris’ folks “elitist,” he’s not wrong, at least as can be gleaned from that data. Thirty years ago, Clinton refocused Democrats on progressive solutions targeted to multiracial, everyday, middle-class folks. But let’s keep it real. I know what you’re thinking: Really? Clinton, a progressive? That doesn’t square with the revisionism we’ve heard, as recently as last week, at our Ideas We Should Steal Festival kickoff, where the brilliant writer and Princeton professor Dr. Keeanga-Yahmatta Taylor posited that Clinton-era neoliberalism essentially got us in this mess.

“If you scratch long enough, eventually you’ll find a human being there. We’ve gotta talk to people.” — Bill Clinton

Well, let’s look at the facts. Had Harris addressed the nation, as Clinton did in 1994 in a primetime address, with a plan called the “Middle Class Bill of Rights” — including a child tax credit, a mortgage-like tax deduction for attending college, and a G.I. Bill for American Workers — maybe she would have had (channeling Lois) a platform to run on other than Democracy, Dobbs and Trump sucks. Only in this case, perhaps her policies ought to have included workforce development and AI?

How is it that we had a national election, and neither candidate put forth a plan for addressing the most disruptive technology we’ve seen in generations? Something like 6 million of our fellow Americans drive a vehicle for a living, and neither Harris nor Trump spent a minute talking about what the hell’s going to happen to them in the age of self-driving cars and trucks.

By and large, Clinton’s reshaping of Democrats into the party of middle-class growth worked not because of his folksy, charismatic ways, but because real people felt the effects of his policies in their real lives. Numbers don’t lie: 23 million new jobs, the highest GDP growth in history, the lowest unemployment rate since JFK, average hourly wages up six percent, median household income up 14 percent, median income of African American families up by 30 percent, Hispanic salaries up $7,000 per year. Over the objection of progressives, Clinton’s welfare reform reduced poverty rates to record lows, as Arthur C. Brooks makes stunningly clear in his contribution to Poverty in America — and What to Do About It.

Ah, but what about inequality? Turns out the Clinton recovery in the 90s was the broadest-based comeback in recent history. From liberal bastion MSNBC:

Incomes for the poorest quintile (i.e., the poorest 20 percent of the population) rose, on average, by only 0.7 percent under Reagan, while incomes for the richest quintile rose, on average, by 23 percent. Under Bush, the country experienced net job loss and a drop in median income, thanks to the 1990-1991 recession and the weak recovery that followed. But the top quintile lost considerably less income, proportionally, than the bottom … Under Clinton, the poorest quintile gained 24 percent and the richest quintile gained 20 percent. Meanwhile, median income increased 17 percent — the most rapid increase since the 1960s.

This is not to say that Dr. Taylor and other progressives are wrong to point out the overreaches of what has come to be called neoliberalism. Clinton’s embrace of free trade was the right policy choice at the time — the rise of a global economy was technologically inevitable — but, as Steven Brill makes clear in Tailspin: The People and Forces Behind America’s Fifty Year Fall — and Those Fighting to Reverse It, the problem lay in paying mere lip service to the job retraining such disruption would inevitably require. And Clinton’s repeal of the Glass-Steagall Act loosened regulation on banks, which critics say contributed to the Great Recession of 2008, though that’s an open question.

I raise this record not just to traipse down memory lane, but to suggest that, just as in 1980, a real political realignment has occurred. We need something like the DLC today — a new paradigm that creates a dynamic center, that marries rights with responsibilities, that calls for collective action. And — this is the tricky part — it has to have a spokesperson like Clinton, a preternaturally gifted pol, who loved people and policy in equal measure.

Imagine political messaging that calls for a new American common project, with the policies to match the rhetoric, just like Clinton and his Middle Class Bill of Rights. A candidate unafraid to go on Joe Rogan and sell that line of thinking? That might be today’s analog to playing the sax on the Arsenio Hall Show or answering young voters’ questions on MTV. If Harris had opted for marrying that kind of depth with that kind of in-her-own-skin comfort level, 51 percent of Americans just might have considered her more likely to have their back.

![]() MORE REACTION TO THE 2024 ELECTION

MORE REACTION TO THE 2024 ELECTION