Last month, an Inquirer story by Sean Collins Walsh delved into the seeming incongruity of Helen Gym, widely seen as the leader of Philly’s progressive movement, not only refusing to condemn, but standing behind, indicted Councilmember Bobby Henon.

![]()

Henon, a longtime Electricians Union operative, faces federal charges of public corruption, misusing union funds and lying to investigators. Still, Gym was not sufficiently bothered by that or the subpar gender and racial diversity record of Henon’s union to rescind her support of him. She didn’t oppose his since-denied quest to remain as Council’s majority leader, saying instead that Henon was “a good majority leader.”

The story revealed the central fissure in Philadelphia politics circa 2020. While other cities find multiple parties—including the Republican party, long extinct here—jockeying for power and arguing about taxes and investments, otherwise known as debating a vision for the future, here we’ve come down to a choice between those who might readily agree on the big issues but whose approaches vary vastly: Reformers versus Progressives.

It’s a schism that matters, because, judging by the results of our most recent election, it could end up empowering the dreaded political machine that has long stood in the way of good government in Philly. But before we get to the effects of the divide on local politics, let’s take a closer look at the combatants on both sides.

![]() The progressives, led by Gym, nationalize local politics, see Republican bogeymen at every turn despite the city’s nearly 8-to-1-D-to-R registration advantage, and double down on class resentment and redistribution while seeming to harbor disdain for the traditional amino acids of politics—coalition building, compromise, and living to fight another day.

The progressives, led by Gym, nationalize local politics, see Republican bogeymen at every turn despite the city’s nearly 8-to-1-D-to-R registration advantage, and double down on class resentment and redistribution while seeming to harbor disdain for the traditional amino acids of politics—coalition building, compromise, and living to fight another day.

Multiple progressive groups, including Reclaim Philadelphia, a descendant of Bernie Sanders’ 2016 campaign, and the The 215 People’s Alliance produced a manifesto in 2018 called The People’s Platform for a Just Philadelphia, and it’s a stunning document.

It reads like a Politburo screed, with nary a mention of once-popular liberal ideas like providing opportunity (as opposed to equality of outcome) and ensuring public safety.

Instead, we get a wishlist of Moscow on the Delaware policies—decriminalizing sex work and drug use, doubling down on sanctuary city status, taking public control of PECO, “severing the city’s relationship with the Philadelphia Industrial Development Corporation,” the public/private entity that drives the city’s economic development, such as it is.

Who represents change, and who represents more of the same? Progressives who speak haltingly when the issue is the long arm of union influence and insider dealing, or reformers who try to make government responsive to taxpayers?

Nowhere have I ever seen so many policies advocated for without regard to efficacy, price tag or an acknowledgment that, politically, there just may be a sizable proportion of citizens who don’t agree with you.

We live, after all, in a state with many powerful Republicans and pragmatic Democrats who just might not sign on to a vision for the future that includes, in effect, wielding a type of eminent domain over private business interests.

The progressive manifesto reads like a high school term paper, the writer of which, in his youthful exuberance, can’t fathom that politics is actually about finding common ground between competing visions.

Purity is the name of the progressive game; reformers may be just as committed to arriving at progressive ends, but are not so rigid in how to get there. They tend to eschew the traditional fault lines of Left versus Right, convinced that there’s no Republican or Democratic way to fill a pothole or create a job. They seek to chip away at a long-entrenched insider culture that is driven by Philly’s own unique type of machine-driven political ideology—call it transactionalism—which, more than the divide that corrodes our national politics, keeps progress at bay locally.

In a city where Republicans long ago agreed to cease to compete in exchange for the crumbs of political patronage, their thinking goes, good government that is transparent ought to be our North Star, leading as it does to accountability and ultimately trust between the governed and those who govern.

Reformers seem to be on the rise elsewhere, as I’ve chronicled. Most prominently, there’s Lori Lightfoot in Chicago, who, on the first day of her mayoralty, stood up to Republicans and Democrats by signing an executive order declaring war on aldermanic prerogative, the Windy City’s version of councilmanic prerogative, which sees district council people empowered to lord over development in their own little fiefdoms, an invitation to graft and piecemeal development that is not part of, and often runs counter to, a vision for the city’s overall growth.

Since then, she’s fired a popular police commissioner for literally falling asleep on the job, passed ethics reform and weathered a teacher’s strike while bringing increased transparency to school board meetings.

No reasonable political observer would confuse Rhynhart, Domb and Quinones-Sanchez for Republicans. All pursue typically liberal policies, but—unlike the progressives—they don’t pander by doubling down on old-school ideological shibboleths.

Reformers tend to value systemic change over old-school party loyalty, as in Syracuse, where Independent Mayor Ben Walsh has recruited Microsoft to open a tech hub in the city as part of his $200 million inclusive growth “Syracuse Surge”—while tussling with a Democratic Common Council, going so far as to veto a pay raise that would have applied to it and to the mayor. Closer to home, there’s the new Independent mayor of scandal-plagued Scranton, Paige Cognetti, a veteran of the Obama administration whose campaign slogan was “Paige Against The Machine.”

So who are our reformers and progressives? Let’s run through the cast of characters:

The Progressives

Helen Gym is not only Philly’s Queen Bee progressive, she’s also vice chair of Local Progress, a growing national network of locally elected progressives that agitates to bring progressive legislation that passes in one city on to others.

Fair Workweek, the $15 minimum wage and fair scheduling legislation in city after city hasn’t just happened; it’s been the result of a coordinated plan. And it’s a plan that seems to value (understandable) class resentments over the hard work of actually creating jobs.

![]() “I see my role as not being a megaphone for those who already have,” Gym said on a recent panel discussion. “Growth on its own is not equal. Growth left to its own devices will favor the powerful over the weak, the connected over the disenfranchised, the bank over the individual. Our goal on City Council is to make sure that those things don’t go on that natural course. We are the balance to that.”

“I see my role as not being a megaphone for those who already have,” Gym said on a recent panel discussion. “Growth on its own is not equal. Growth left to its own devices will favor the powerful over the weak, the connected over the disenfranchised, the bank over the individual. Our goal on City Council is to make sure that those things don’t go on that natural course. We are the balance to that.”

Shouldn’t an elected official aspire to represent everyone, as opposed to stigmatizing “those who already have”? Divide and conquer politics may garner votes, but it doesn’t bring people together—whether it’s deployed from the left or the right.

Like Gym, freshwoman Councilmember Kendra Brooks seems to place ideology over practical problem-solving that works toward progressive ends.

“There is plenty of wealth in this country and this city,” she said during her groundbreaking outsider campaign for Council. “Our problem has never been if we have enough money, but instead if our elected officials have the political courage to check the powers of the 1 percent and to demand funding for resources for poor and working people. As a City Councilperson…I will always look for laws that lessen and abolish white supremacy and patriarchy in our system, and that uplift Black and Brown people, women and gender non-conforming people. To me, this starts with fully funding our education system, [and] ensuring accessible affordable housing for all people.”

Progress comes in fits and starts, and when it does happen, it’s usually because people of opposing convictions have listened to one another and made some accommodations based on what they’ve heard.

Let’s put aside the fact-checking, save for noting that Philadelphia decidedly does not have “plenty of wealth.” In a city in which more than two-thirds of all jobs created since 2009 pay less than $35,000 a year, we’ve played the redistribution game and have effectively run out of that which to redistribute. Rather than respond to Trump’s soullessness and incompetence with localized versions of Bernie Sanders’ rhetoric, why not talk about what Philly really needs: good government reform, practical problem-solving and jobs, jobs, jobs.

Which brings us to today’s patron saint of progressivism, District Attorney Larry Krasner. For all their strong opinions, the ancestors of today’s progressives—elected officials like George McGovern and Bella Abzug come to mind—were willing to work with anyone in order to get things done. Not so this new strain, which seems obsessed with team colors.

Krasner is Exhibit A: All he seems to do is fight and call names, jumping from nemesis to nemesis. He tussled with fellow Democrat Josh Shapiro, the politically odious Police Union head John McNesby, and even his own office, which he called “a cover-up organization” as a candidate.

It’s the politics of self-righteousness, and it flies in the face of what we’ve learned over the past 240 years: That progress comes in fits and starts, and when it does happen, it’s usually because people of opposing convictions have listened to one another and made some accommodations based on what they’ve heard.

The Reformers

The election of progressive Krasner coincided with the rise of reformer City Controller Rebecca Rhynhart. She’s been a chart-wielding apostle of transparency, and has become the city’s chief watchdog on issues ranging from the beverage tax to fiscal responsibility to the procurement of voting machines.

Another good government thorn in the side of Mayor Kenney and the permanent establishment has been Councilmember Allan Domb, who has proposed term limits for Council, and, observing that Philadelphia taxes its poorest residents at a higher rate than any competing city, advanced a bill ultimately not signed by Kenney that would have offered a wage tax rebate to low-income workers, as ambitious a move in the war against our worst-in-the-nation poverty rate that we’ve yet seen.

Finally, there’s Councilwoman Maria Quinones-Sanchez, a pragmatic progressive, the only elected official to call for Henon’s resignation and someone who has defeated the political machine time and again.

And whither Mayor Kenney? To what camp does he belong? His supporters say he’s a progressive, but can you be if your foremost allegiance is to the building trades?

I’m reminded of how expertly Ronald Reagan played the far right, plying them with pro-life and fiscally responsible rhetoric, but not actually moving the needle much on his base’s issues. Perhaps Kenney is what he’s always been—a transactionalist, an old-school politico who learned at the knee of Vince Fumo.

No reasonable political observer would confuse Rhynhart, Domb and Quinones-Sanchez for Republicans. All pursue typically liberal policies, but—unlike the progressives—they don’t pander by doubling down on old-school ideological shibboleths. They realize that being a progressive on national issues might not quite fit locally.

![]() After all, if you’re a proud supporter of the American labor movement—as well you should be—that means turning a blind eye to thuggery and shady political dealings locally. When a video surfaced in 2016 of the since-indicted labor leader John Dougherty coming to blows with a nonunion worker on a city street, where were the progressive elected officials denouncing such behavior? Or how about when some goons from the Philadelphia Ironworkers Local 41 torched the Chestnut Hill Quaker Meeting House for using nonunion labor on the job? Yes, the perpetrators went to prison, but what did we hear from local liberals who, in other circumstances, are the first to express compassion for those who are bullied by the powerful? Crickets.

After all, if you’re a proud supporter of the American labor movement—as well you should be—that means turning a blind eye to thuggery and shady political dealings locally. When a video surfaced in 2016 of the since-indicted labor leader John Dougherty coming to blows with a nonunion worker on a city street, where were the progressive elected officials denouncing such behavior? Or how about when some goons from the Philadelphia Ironworkers Local 41 torched the Chestnut Hill Quaker Meeting House for using nonunion labor on the job? Yes, the perpetrators went to prison, but what did we hear from local liberals who, in other circumstances, are the first to express compassion for those who are bullied by the powerful? Crickets.

Likewise, if you’re really a progressive, you should have a reverence for good government. So why are you mum when Mayor Kenney makes Dougherty’s chiropractor the head of the Zoning Board, a perfectly legal move, but one that undermines the public trust and values private interests over the common good? (Chiropractor James Moylan eventually stepped down from the Zoning Board, after his home and office were raided by FBI agents investigating Dougherty. He, too, was subsequently indicted).

The progressive manifesto reads like a high school term paper, the writer of which, in his youthful exuberance, can’t fathom that politics is actually about finding common ground between competing visions.

Similarly, yes, criminal justice reform is long overdue. Mandatory minimums, cash bail, a probation and parole system that actually feeds mass incarceration—all are ripe for urgent change. But to be a Krasner movement loyalist, do we have to countenance his dissing of the victims of crime? Do we have to be on board with reduced sentences for murderers that could find them back out on the streets in 15 years or less?

So why does all this matter, you ask? If reformers and progressives are skirmishing, isn’t that just an internal Democratic family squabble? Well, not quite. It matters profoundly because it runs the risk of emboldening machine politics. Look no further than the results of our most recent election. For all the buzz around Kendra Brooks’ election and Gym’s high at-large vote total, the machine actually fared rather well.

Not only did Democratic City Committee’s endorsed candidates for Council go five-for-five, three of the more impressive reformers lost: Eryn Santamoor, whose platform for change on Council was as smart as any in recent history; and Kahlil Williams and Jen Devor, arguably two of the most qualified candidates for City Commissioner we’ve yet seen.

That progressives seemed unenthusiastic for these campaigns does not bode well for the prospects of meaningful change in the future. It begs the question: Who represents change, and who represents more of the same? Progressives who speak haltingly when the issue is the long arm of union influence and insider dealing, or reformers who try to make government responsive to taxpayers? Most citizens are not ideological. They just want their government to work for them, and not for the same insiders who have long fed at the public trough.

Clarification: This story was amended slightly after Councilmember Gym’s office pointed out that she has been vocal about addressing racial inequities in the building trades.

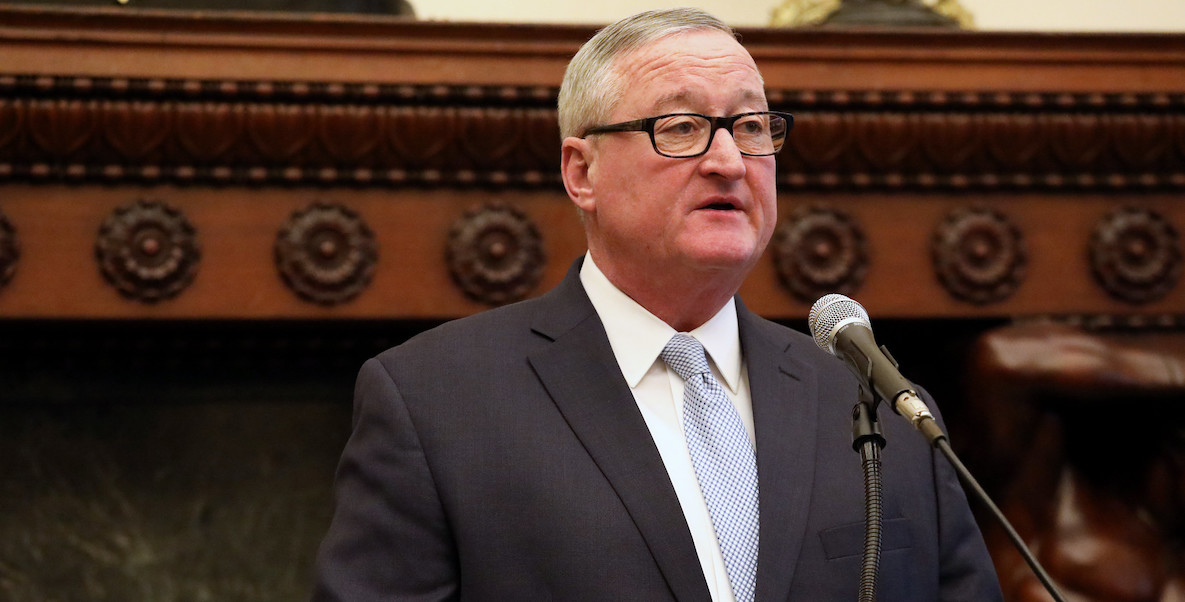

Header photo courtesy Philadelphia City Council / Flickr