As they near the end of their term in office, elected officials tend to make one final argument. Under the guise of setting the record straight, they attempt to secure their legacy. Newspaper and TV interviews ensue, with the soon-to-be-whisked-away public figure telling us: Remember me this way.

So it is now with Jim Kenney, as he enters the final week of his mayoralty. The Mayor’s team has inundated media inboxes with press releases, and he has sat down with The Inquirer editorial board and subjected himself to grillings on WHYY and 6ABC’s Inside Story. Throughout, Kenney has said he wants to be recalled as, “someone who cared,” a rather low bar: Have we had a mayor who didn’t care?

A makeover in public perception is challenging at this point, because Kenney seemed to write his own political epitaph back on July 4, 2022, when, in a fit of frustration after yet another public shooting, he said, “I’ll be happy when I’m not here — when I’m not mayor,” seeming to quit on his own city.

“Leaders are visionaries with a poorly developed sense of fear and no concept of the odds against them.” — Dr. Robert Jarvik, inventor of the first permanently implantable artificial heart

Now, I happen to agree with the Mayor that media made too much of his gaffe. But that was because his comments spoke to a larger truth: His lack of joy and vision, his perpetual frown. Even in his first term — long before the pandemic, the racial uprisings, and the 500 murders per year — he’d tell perfect strangers (including my own sister) at bars that he couldn’t stand his job. (“I was relieved when my table was ready,” my sister said. “He was getting me depressed.”)

Now, as Kenney goes on his closeout spin tour, as we’re thankfully moving on from Mayor Morose, an interesting — not to mention fallacious — conventional wisdom is taking hold. It was the pandemic that did him in, the thinking goes, and all those other things in his second term over which the mayor had no control: A perfect storm of crises. It was, in the words of 6ABC anchor Matt O’Donnell, “a tale of two terms.”

So let’s dive in. Was Kenney’s second term the outlier? Or were the seeds for his failed mayoralty actually planted in his first term, contrary to the storyline now forming?

What did Kenney actually accomplish?

Now’s a particularly good time to ask. As Mayor-elect Cherelle Parker readies to take office, a search for early hints of her predecessor’s fatal flaws can only help her avoid a similar fate. Clearly, in his second term, Kenney’s unique drawbacks were exposed: He was neither visionary leader nor the unsexy blocker and tackler capable of coaxing a bureaucracy into action. Well before the pandemic, there was glaring evidence that Jim Kenney wasn’t up to actually making government work for real people.

It seems common wisdom now that Kenney’s first term contained a breakthrough win. “In his very first budget proposal to Council, Kenney unveiled what has turned out to be by far his most significant policy accomplishment: a new tax on sweetened beverages,” writes the Inquirer’s Anna Orso and Sean Collins Walsh. Only one problem, of course: A tax is not a policy.

The actual policies Kenney’s tax was intended to fund were his pre-K program and Rebuild, an ambitious, and long overdue, refurbishing of parks and recreation centers. How’d he do on the policy — and not the funding — front? Well, early in Kenney’s term, pre-K came out of the gate inauspiciously, leading one to wonder if the new mayor would be able to pull off a groundbreaking new program to go with his groundbreaking new (regressive) tax. Turns out, fully one-fourth of all pre-K programs Kenney green-lit had missing or incomplete FBI, state police or child abuse clearances; others owed hefty real estate back tax bills.

While those kinks have since been ironed out, it’s now nearly eight years in and the question has to be asked: What return has pre-K wrought? After all, 72 percent of third-graders don’t currently read at grade level. In the absence of pre-K, could we have possibly done worse? Besides, in a state without mandatory K, how imperative was it? Would we have been better off further funding K through 8 instead?

Throughout, Kenney has said he wants to be recalled as “someone who cared,” a rather low bar: have we had a mayor who didn’t care?

Rebuild’s is a similar story, raising real questions about the mayor’s ability to competently implement a bold new program. It was pushed by the mayor’s chief political benefactor, now-convicted labor leader John Dougherty, and was supposed to remake some 200 rec centers and parks. To date, all of 17 have been completed.

Public safety? Kenney took over a city from his predecessor with a 60-year low homicide rate and presided over a historic and tragic increase — the two worst years of murder and mayhem in our city, with 562 and 514 lost souls, respectively, a record number of shooting victims, and a menacing sense of disorder in the air.

This year, Kenney has overseen a laudable year-over-year 25 percent drop in homicides. But a recent administration Gun Violence Prevention Progress Report was a case study in convenient spin.

“A recent study showed that gun deaths rose 43 percent in America’s big cities during the Covid-19 pandemic, with an estimated 22 gun deaths occurring daily in these cities at the pandemic’s height in 2021,” reads the report. In other words: It’s the pandemic, stupid. The report notes that homicides have dropped 26 percent since 2021. But making 2021 the point of comparison is to slyly double-down on the proposition that the pandemic was the driving force behind our murder epidemic. Fact is, murder exploded here long before the pandemic and before other cities experienced the same surge in violence.

Let’s look at the numbers. In Kenney’s first year, murder essentially held steady; after that, it grew by 27 percent throughout the course of his first term. (And a whopping 45 percent in his second term.)

In that first term, Kenney disbanded a focused deterrence policing pilot in South Philly that lowered the homicide rate by 35 percent in three police districts — presumably because it was a favored program of his predecessor. When the outcry over the proliferation of body bags and chalk outlines got too loud, Kenney brought back a new version of the aggressive strategy — GVI, or Gun Violence Intervention. It currently exists in 15 police districts and, in its laser-like focus on intervening in the lives of those known to be part of Philadelphia’s shoot first culture, it is widely credited for this year’s drop in the murder rate.

But Kenney had to be shamed into bringing back a strategy that has worked throughout the nation, and did so as a pilot — despite the fact that there’s nothing experimental anymore about the efficacy of focused deterrence.

Big spending, little accountability

Okay, but how about fiscal matters? Under Kenney, Philadelphia’s operating budget exploded — going from $3.9 to $6.2 billion — and the pension fund is in better shape than at any time in recent memory. The city has a viable rainy day fund. All good stuff, which Mayor-elect Parker cited when announcing that she’d be retaining longtime Finance Director Rob Dubow.

But let’s return to that first term, which many seem to have forgotten about. Remember how Dubow and his team couldn’t find some $33 million in city deposits and it turned out the city hadn’t reconciled its own bank accounts for seven years? Is there a CFO in private industry anywhere who would be retained after regularly not balancing the company’s books? Worse, the administration exhibited a stunning allergy to accountability. When asked if anyone would be fired over the accounting mistakes, then-Chief of Staff Jim Engler said, “No, that’s not how we operate.”

At the end of Kenney’s first term, then-City Controller Rebecca Rhynhart released an eye-opening report outlining the degree to which Kenney had essentially used the Philadelphia taxpayer as an ATM machine for career politicians and apparatchiks.

Mayor-elect Cherelle Parker hasn’t even taken office yet, but her upbeat persona is already a breath of fresh air.

In Kenney’s first term — before all the crises — he added over one billion dollars to the City’s budget, the largest spending binge in our history. Payroll expenses surged 8 percent as Kenney added nearly 1,000 workers to the City workforce — at the same time that overtime costs exploded, itself a red flag: In reasonably-run governments, when full-time workforces shrink, overtime justifiably rises. In governments where bloat and waste rule the day, full-time workers and overtime simultaneously expand, which Rhynhart found to be the case in 7 of 11 of the City’s biggest departments.

Mistakes happen in government, yes. But a pattern emerged in Jim Kenney’s first term of someone incapable of turning the levers of government in a competent and efficient way. And it presaged the calamities of his second term, when he put a 22-year-old student in charge of the city’s largest vaccination program, when he stood by and watched rioters destroy neighborhood business and whole city blocks, and when he funded community groups with hundreds of millions of dollars of anti-violence dollars with no real goals, timetables, or accountability system in place.

The signs were there, for all to see. Corruption? Kenney effectively turned City Hall over to Dougherty. Remember, during the soda tax debate, when he showed up to a meeting with soda honcho Harold Honickman not with Council President Darrell Clarke, but with his real partner in governing, Dougherty? Nice little soda company you got there. It would be a shame if something happened to it. Or when he made Dougherty’s chiropractor the head of the zoning board, before said apparatchik was convicted of embezzlement?

And then, when his guy does get convicted, does he lament Dougherty’s thuggish actions — like the extorting of CHOP into using union labor to install MRI machines? Does he align with the rank and file whom Dougherty stole from? No. He disagrees with a jury verdict of his own citizens and expresses his sadness for his criminal friend.

That is the essential legacy of Jim Kenney — a historic tone-deafness. Early in Kenney’s first term, he received a call from a group of his fellow mayors. Los Angeles’ Eric Garcetti and South Bend, Indiana’s Pete Buttigieg were among those coming to Philly to share best practices. Could the mayor join them, maybe take them on a tour? Negative, Kenney responded. Maybe he could send someone to show them around.

It was to become a thing: Other mayors wondering just what’s up with the guy from Philly, who tends to stay by himself at the bar or alone in his hotel room during those U.S. Conference of Mayors confabs. Where was the intellectual curiosity? The passion to learn and to lead? No wonder here we are, left to ask just what do we have to show for all of Jim Kenney’s big spending and whiny moping? We’re still the poorest big city in America, with disorder rampant on our streets and a chronic lack of opportunity on offer to our fellow citizens.

Look, Jim Kenney wants us to remember him as someone who cared. Let’s do that. But that ought to be the baseline, no? In government, good intentions are not quite enough, are they? So what’s Jim Kenney’s real legacy?

Well, it’s become axiomatic by now that cities take on the personality of their mayors. Under Ed Rendell’s relentless cheerleading, Philly became the little city that could, a Rocky-like underdog. Under John Street, a long-overdue correction took place, as far-flung neighborhoods, long starved of services and investment, got, for a time, what was rightly theirs. Under Michael Nutter, technocratic rule came to the fore, and with it came a flock of millennials, contributing a sense of vibrancy on our streets not seen since the heady reform days of Richardson Dilworth.

Is it, then, purely coincidental that, with a mopey, sad sack mayor, Philadelphia is ranked as one of the nation’s least happy cities? According to a study by WalletHub, Philly ranked 160th out of 182 cities due to the emotional, physical and employment well-being of those surveyed. Jim Kenney ought to be remembered as a complainer-in-chief, when what we needed was a vision for turning our grievances into positive collective action.

Which is where Mayor-elect Cherelle Parker comes in. She hasn’t even taken office yet, but her upbeat persona is already a breath of fresh air. “Leaders are visionaries with a poorly developed sense of fear and no concept of the odds against them,” said Dr. Robert Jarvik, inventor of the first permanently implantable artificial heart. He may as well have been speaking to us, Philly, at this very moment.

![]()

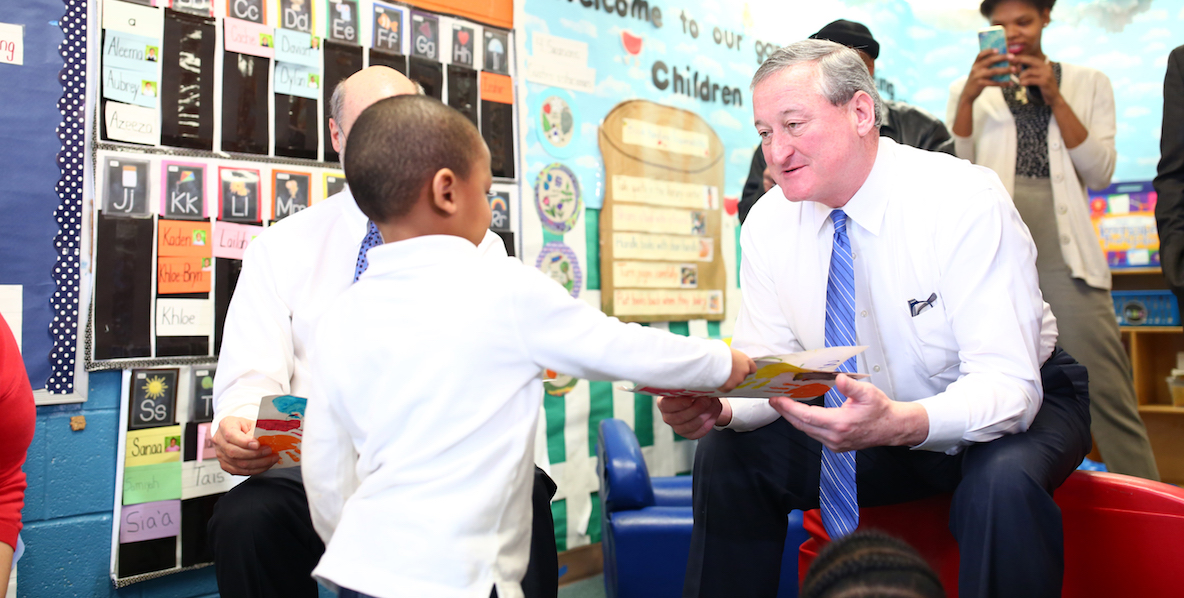

A LOOK BACK AT JIM KENNEY AS MAYOR OF PHILADELPHIA