Thirty years ago, a buddy of mine who’d been a radio producer for WNBC in New York slipped me George Carlin’s home phone number. I was a ponytailed law school dropout, who, while figuring out what I wanted to be when I grew up, had started penning a weekly column in the Philadelphia City Paper (RIP), a classic alternative weekly.

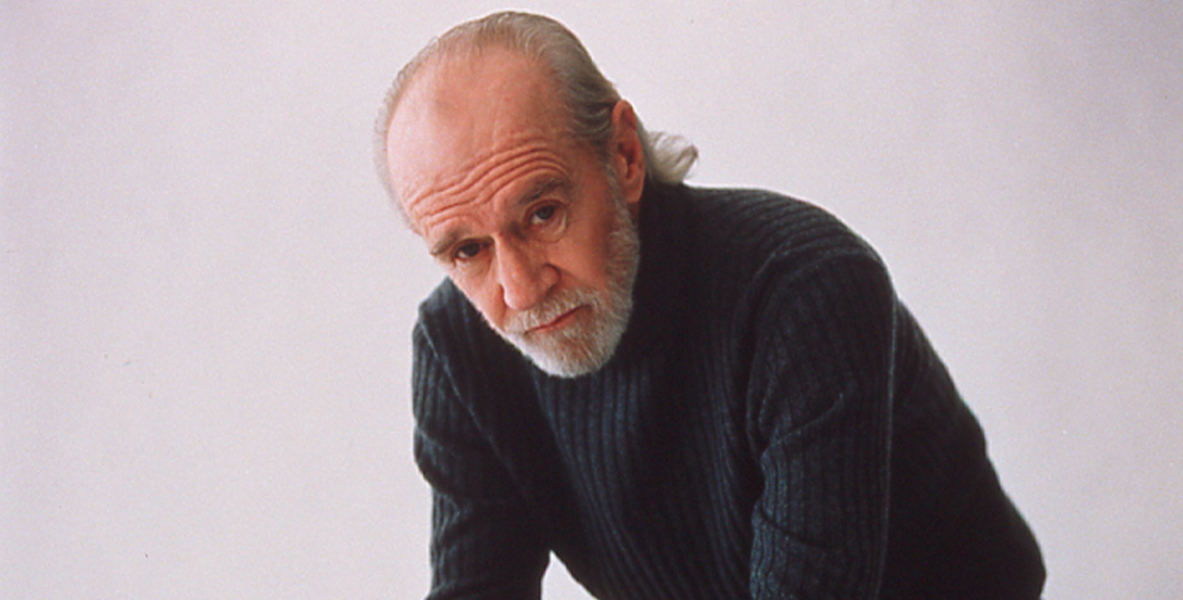

Carlin, as chronicled movingly in Judd Apatow and Michael Bonfiglio’s new HBO definitive documentary George Carlin’s American Dream, had just redefined himself yet again — in the alternative tradition. He’d been the stoner counterculture comic in the ‘70s; the wry, pre-Seinfeldian observationalist in the ‘80s, and now here he was in the ‘90s: righteously angry, turning his biting wit onto the race and class divisions that had created two Americas.

While Democrats cowered in the aftermath of Reaganism, Carlin routines may have been the best critiques going of a zeitgeist that had turned its back on New Deal communitarianism, like the bit that argued for turning golf courses into housing for the homeless:

More than perhaps anyone save Mark Twain and Richard Pryor, Carlin was a moralist, a humanist, and a humorist — all wrapped in one.

That was the context for my calling him, at his home. I wanted to interview him, particularly about sports. Judging from his act, his fandom wasn’t a mere facet of his personality. It was integral to who he was, to the building of his egalitarian worldview — a trait I shared, I told him. Muhammad Ali’s courageous stand against the Vietnam War and Jackie Robinson’s breaking of the color line — seven years before Brown v. Board of Ed — had shaped everything about me, and I wanted to know if the same were true of him.

“How’d you get my number?” I remember him asking.

I told him the truth, and detected a faint chuckle. “I’ll tell you what,” he said. “I’m going to be performing in Atlantic City next month. Give me your phone number. We’ll talk then.”

A blow-off, right? Sure enough, on a Saturday morning four weeks later, there was George Carlin on the phone. We spoke for an hour. I wish I still had the notes, or even the pieces I’d go on to write about him. (This was pre-Internet, y’all.) But I remember him explaining that he’d grown up in working class “White Harlem,” on the upper west side. Other kids were Yankee or New York Giants fans. Of Yankee fans he had particular disdain: “These people would go to ballgames in suits,” he sneered.

Rebellious by nature, he was drawn to this quirky band of lovable also-rans a world away … in Brooklyn. There, a groundbreaking experiment in racial equity was underway. There, working men and women filled the stands, and were on a first-name basis with ballplayers with names like Pee Wee, Jackie and Duke, with whom they shared the same streets, drug stores and restaurants. There was no daylight between town and team; the Dodgers — lovingly nicknamed “Dem Bums” — were Brooklyn, and Brooklyn was the Dodgers.

It was a whole different way of seeing the world, Carlin said. More heart, less commerce. I remember telling him that, here in Philly, where you stood on, say, Dick Allen — the Black Phillies star in the early ’60s who was essentially run out of town by racist fans and media — was a perfect predictor of where you’d be a few years later when it came to the Vietnam War or Richard Nixon.

“I fucking hated you guys,” Carlin muttered, a reference to how Philly treated Robinson, subjecting him to more hate than any team in the league. The Phils’ manager at the time, Ben Chapman, would stalk the dugout steps, calling Robinson the N-word for much of the stadium to hear.

“Every person you look at, you can see the universe in their eyes, if you’re really looking,” Carlin once told Charlie Rose.

I wrote a piece about how sports had shaped Carlin’s worldview, and my own, and sent it to him. He called to thank me, and to invite me and my then-girlfriend, now wife, Bet, to visit him backstage the next time he performed in the area. So there we were at the now-defunct Valley Forge Music Fair, where he just killed. The first Gulf war had just broken out:

“We like war,” he said. “We like war because we’re good at it … and it’s a good thing we are. We’re not good at anything else anymore. Can’t build a decent car. Can’t make a TV set or a VCR worth a fuck. Got no steel industry left. Can’t get healthcare to our old people. Can’t educate our young people. But we can bomb the shit out of your country all right.”

Afterwards, we embraced. “You did a nice job with that piece, man,” he said. “That’s one of the best pieces done on me. You get it.” I don’t know; maybe what I wrote was hagiographic crap, which is why he liked it. But the fact is that, until then, I’d been playing at writing — it was just something to do after my law school debacle, having lasted all of 10 minutes in a contracts law class. Now here was a brilliant writer offering me words of encouragement. “Be cool,” Carlin said when we left. In the car, Bet said, “I think George Carlin is your friend.”

Over the next few years, we’d check in with one another. I wrote a magazine piece on the inanity of golf that cried out for his voice. Once he called to ask for my address; in the mail promptly came a package, a DVD boxed-set documentary series on the Brooklyn Dodgers.

Another time, I remember us talking about how sports fandom was really a way to wear your values. We were both long-suffering fans; he, of the Brooklyn Dodgers and Knicks, me of all the Philly perennial also-rans. We were both raised to believe that suffering breeds character and that the worst sin, as a fan, was to be seen as a bandwagon jumper. But around the time his Knicks became dominant in the mid-90s behind Pat Riley and Patrick Ewing — a pugnacious team that played the game with the same ferocity Carlin brought to stand-up — he told me he’d been rethinking his youthful views on sporting loyalty.

I remember once lamenting to Carlin that Jackie Robinson, his hero, had turned around and campaigned for Richard Nixon to be president. It wasn’t Robinson who had betrayed me, Carlin explained. It was I — the unthinking liberal — who was insisting that the icon know his place.

“At a certain age, you start to accept that when your teams lose, they’ve gone away from you,” he said. He’d learned to let losing teams go. “My Knicks have come back to me, now.”

I’d say we were only in touch for 5 to 10 years, and I’m not sure why we fell out of contact. Maybe I didn’t feel I had much to offer? But now comes this documentary, and it turns out that Carlin’s generosity of spirit towards me was kind of like his thing. Other comedians, like the late Garry Shandling, talk about how, as unknowns, they’d show up at comedy clubs with jokes for him, and he’d read their stuff, pepper them with questions, and mentor away.

That he was so sweet to virtual strangers was keeping with a Carlin ethos: “I love individuals,” he once told Charlie Rose on PBS.

“I hate groups of people. I hate a group of people with a common purpose. ‘Cause pretty soon they have little hats. And armbands. And fight songs. So, I dislike and despise groups of people but I love individuals. Every person you look at, you can see the universe in their eyes, if you’re really looking.”

I remember once lamenting to Carlin that Robinson, his hero, had turned around and campaigned for Richard Nixon to be president. It wasn’t Robinson who had betrayed me, Carlin explained. It was I — the unthinking liberal — who was insisting that the icon know his place. “Robinson wasn’t the liberal, Branch Rickey was,” Carlin said. “He’d spent his whole adult life listening to liberals demand he turn the other cheek. Of course he’d rebel.”

In that one exchange was so much of Carlin: His empathy, his insight, his free-thinking. He was an iconoclastic thinker with little time for shibboleths of the left or right. It’s become trendy of late for those on the pro-choice side of the ledger to cite his bit about abortion, especially when he suggests that, to pro-life conservatives, “if you’re pre-born, you’re fine. If you’re pre-school, you’re fucked.”:

But then check out his brilliant evisceration of the environmental movement, exposing its limousine liberalism, and take special note of his prescience when it comes to fantasizing about how the earth just might lay humans low: Via a virus. Agree or not, you have to concede the dude wore no team colors:

I remember once buying for myself a vintage Brooklyn Dodgers windbreaker — the kind Jackie used to sport around town — and thinking, I oughta get one for George, too. But I didn’t. Not really sure why. The natural entropy of relationships or some such.

In 2008, when he died at 71, I don’t remember being particularly broken up. But now comes this doc, and there’s George Carlin, in all his humanity, gentleness and fiery brilliance, back in force, and it feels like such a sweet surprise.

![]()

MORE ON FILM AND COMEDY FROM THE CITIZEN

Ideas We Should Steal Festival 2020: Comedy as the New Frontier of Journalism

Courtesy of the George Carlin Estate / HBO