There is something uniquely badass about earning your way into some of the most elite institutions in the world — and then publicly calling them out for turning a blind eye to the inequities they’ve helped fuel.

So it was especially gratifying to watch a recent talk given by Hillary Do on the campus of Stanford University, from which Do graduated with an MBA, and hear her point to the school’s role in our country’s widening wealth gap.

“Take a look around,” she says to the audience before her. “We are sitting in an institution with a $37 billion endowment. Stanford’s highest-paid employee makes $8 million. Hugging the western edge of campus is Sand Hill Road, the epicenter of venture capital and the most expensive street in all of America. At the same time, on El Camino Real, which hugs the northeastern edge of campus, dozens of RVs are parked, filled with people just trying to get by.”

Later, she adds: “What may look perfect from your vantage point, looks like hell to someone who doesn’t have that privilege.”

To be sure, Do could have easily been a part of the privileged class in Palo Alto, or anywhere else. A first-generation American whose parents overcame myriad hardships to come to Philly from China and Vietnam (her father was one of the “Boat People,” a group of refugees from Bidong Island), Do graduated from Central High School, then went to Harvard. She handily landed a job at a tech company, earning six figures, unlimited vacation, free meals … you name it. But as the story often goes, Do’s lifestyle, perfect on paper, left her feeling empty.

“Everything I had, that my parents immigrated to this country for, meant little if there were people still struggling like we once did,” she says.

What she longed for was the sense of community and possibility she’d found back at Central, when she’d been active in various causes like electoral organizing, and interned for local government, and took a stand for public education when the School Reform Commission was in charge, regularly showing up at 440 North Broad with her classmates to campaign for change. She missed the sense of passion ignited by Central teachers like Thomas Quinn, of PA Youth Vote, and Kenneth Hung, of Asian Americans United, who taught Contemporary Issues and encouraged students to read The New York Times every day and debate what they learned.

“Everything I had, that my parents immigrated to this country for, meant little if there were people still struggling like we once did,” Do says.

“I kept thinking about all the people who are doing really incredible work in their neighborhoods but are so under-resourced and underfunded,” she says. “I realized that people-power is the key to change.”

That insight is what led Do to create Philly BOLT, a nonprofit with the vision “for every neighborhood to thrive, led by the people living there.” Do’s goal: Empowering oft-overlooked, oft-underfunded community leaders with the skills they lack only because they haven’t had exposure to them, like Do and her classmates at the Harvards and Stanfords of the world do.

“I don’t think the barrier to learning all of that is that high when you make it accessible to everyone,” she says. “And I think that people who have lived experience should be the ones at the helm of change. They have much more trust and respect in their community than outside stakeholders. They know what solution works because they’re living in the communities and have firsthand experience of the problems that are occurring. And they also won’t leave just because a problem gets hard, which outside stakeholders often do.”

Piloting a path forward

In 2019, Do moved back to Philly, where she worked for Philly Counts, making sure that immigrant communities were counted in the Census. Then she joined a national organization doing electoral work. Trouble was, that national organization wasn’t interested in local partnerships, despite Do pushing them to collaborate. “I’d say, There are people already doing the work in these communities — why are we starting from scratch, why don’t we work with what’s already there? And they were not very supportive of that.”

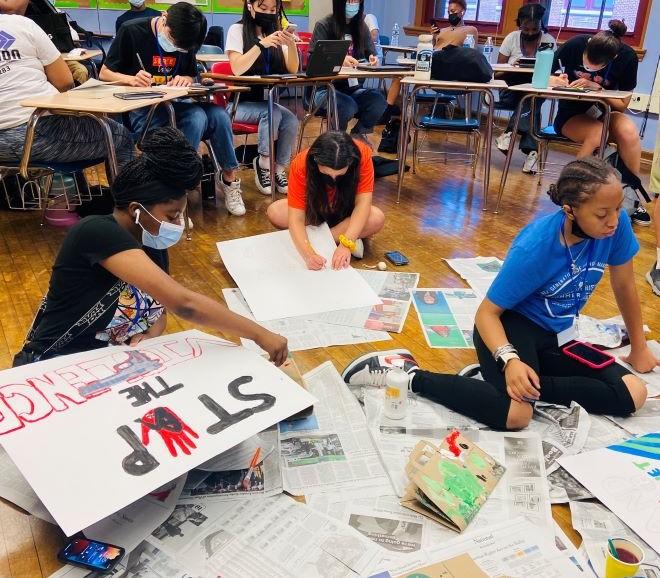

That experience, while demoralizing, crystallized Do’s mission. “I saw all these people doing incredible work in communities. And I wanted to support them, to accelerate their work and make it even more impactful,” she says. She moved to the West Coast to attend Stanford and, during her summer break, piloted a program called Community Rising, in partnership with Quinn’s PA Youth Vote, to train and support high school activists.

After graduating from Stanford, she moved home for good in 2022 and launched Philly BOLT. The organization executes its mission through three programs. There’s the six-week summer youth program for high school students; a five-month school-year program for high school students; and an adult program, BOLT School for Grassroots Leaders.

The teen programs nurture high school students from throughout Philadelphia to become leaders at the city and state level. Field trips last summer included a visit to Harrisburg, where students spoke at a gun violence rally. Teens also visit with City Councilmembers, and learn lessons on topics like how the ward system works. Alongside Do, fellow teachers include Jude Husein, Philly BOLT’s chief of staff, as well as elected officials, issue area experts, and many other grassroots leaders.

BOLT School for Grassroots Leadership runs over eight months, four hours per week, and includes 1:1 coaching sessions with Do. Topics range from budgeting and developing a board to fundraising, Theory of Change approaches, and adaptations of exactly the kinds of management, fundraising, and leadership training Do absorbed during her time at Harvard and Stanford.

“So much of that knowledge is gatekept. It’s a problem when ‘insider knowledge’ exists because the next question is, Who’s on the outside? And for the most part, the people who have the most expertise and are doing the most impactful work — grassroots, community leaders — are the ones most severely under-funded and under-resourced,” she says.

Do quickly points to the flipside of that equation: “Imagine what would happen if they did have access to knowledge, networks, and other resources that are being gatekept. I know their impact would be even more immense than the organizations that do have that access, but are not led by community members. To me, it’s not just about sharing that insider knowledge: It’s about breaking down the barriers to gatekept knowledge so the concept of ‘insider’ and thus ‘outsider’ doesn’t exist.”

A targeted approach

To recruit applicants for all of BOLT’s programs, Do conducts outreach to schools and fellow grassroots leaders, and she combs Instagram regularly, recognizing that some of the most hardworking community organizers don’t have the resources to develop sleek websites, and instead rely on social media to communicate with the people they serve.

Critically, participants in all programs are paid for their time; adults earn $32 per hour, and teens earn $15. Philly BOLT currently operates on an annual budget of about $240,000; funding has come largely through grants — like NewSchools Venture Fund’s Racial Equity grant, Institute for Citizens & Scholars, WorkReady (which pays youth $11 per hour during the summer, with Philly BOLT fundraising to close the gap to $15/hour), and Stanford Impact Founder Fellowship. Recently Philly BOLT won $50,000 from the Commonwealth to help fund the School for Grassroots Leadership next year.

“What does the American dream mean if we can’t all have it?” asks Do.

Rehanna Griffiths, now a junior at Parkway Center City, says Community Rising was transformative. “Before I joined Community Rising last summer, I was the type of person who was scared to share my voice or my opinions, because I was scared of what someone else would think,” she says. “But Community Rising made me realize that my opinions do matter, and what I have to say might help someone, or help people come together.” She’s currently enrolled in Philly BOLT’s school year program.

Do says Philly BOLT has a very targeted approach, doing outreach in particular zip codes, because she wants to support leaders in neighborhoods that have been overlooked and continue to be overlooked.

“Center City is going to be fine in Philadelphia. Fishtown is probably going to be fine, too. Northern Liberties. But there are people in neighborhoods that have been overlooked and continue to be overlooked that are really doing the work to really make sure their communities can thrive,” she says.

Take Ryan Harris, founder of As I Plant This Seed, a North Philly nonprofit that has become a community hub for youth and families, with the mission of promoting youth development and community advancement. Or Tahira Fortune, who lost her son to gun violence. Fortune created a support network for other grieving mothers and launched safe spaces for youth to get support like homework help. Or Milaj Robinson, who co-founded Youth Creating New Beginnings while he was a student at Philadelphia Electrical and Technology Charter High school before going on to Moorehouse College.

Robinson says that Philly BOLT and Do have played a huge role in his professional development. “Philly BOLT has helped me so much when it comes to the administration side of things: documentation, organization, management, budgeting. The program has helped me with my infrastructure and seeing my vision more clearly.” Plus, he says, the group really does feel like a family, a support network of like-minded people who just want to make a difference.

“We really believe that focusing the attention on people with lived experience is so important because lived experience can’t be replaced,” Do says. All of those soft skills and hard skills that go along with the educational pedigrees and awards? Those things, she says, anyone can learn.

Of course, Do says, she has a lot of respect for her classmates from college and grad school — but she wants the Ryans of the world, the Tahiras and Milajs and Cleos and Seritas and countless others like them to have million-dollar budgets to work with, too. (Rather than, say, the financial hardships that have forced Robinson — with his hard work and dedication, his passion and drive — to take a semester off from Moorehouse.)

And so Do will do what she can to transfer her knowledge and experiences to folks who haven’t had the access to places and spaces like she has. She will champion them, and also do her part to challenge those who wield both power and money. Speaking at Stanford, in a red t-shirt emblazoned with the words “change takes courage,” Do left her audience with questions that she hopes to tackle through Philly BOLT — and that we should all be asking ourselves, and others:

“What does the American dream mean if we can’t all have it?”

“What does it mean when the barriers are so high, only a few can access it?”

“What does it mean when we continue to leave the same people behind?”

![]() MORE ON PHILLY ACTIVISM FROM THE CITIZEN

MORE ON PHILLY ACTIVISM FROM THE CITIZEN