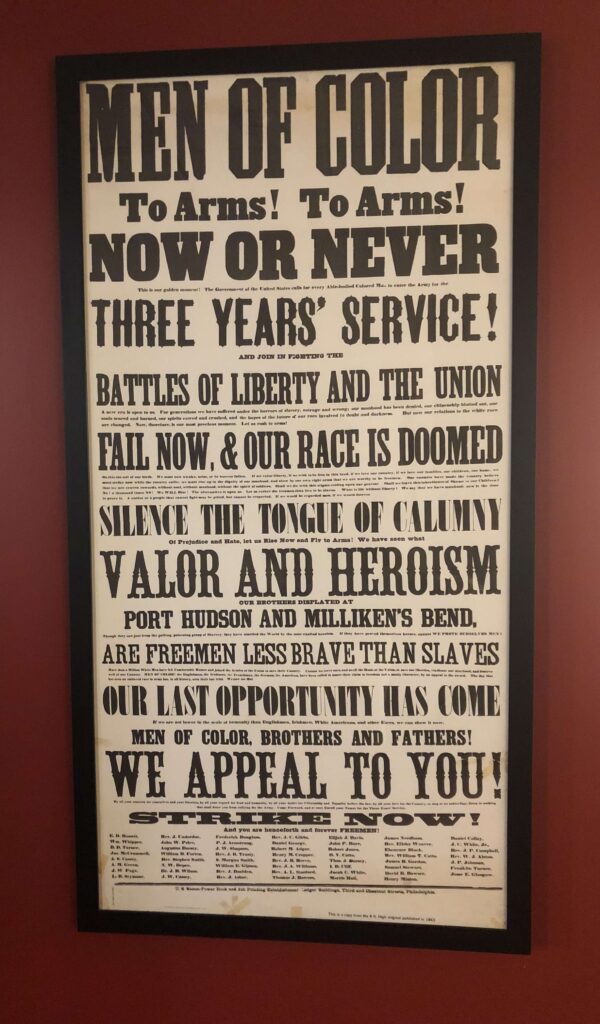

“Men of Color, To Arms! Now or Never!” reads the emphatic, titular opening of an 1863 broadside designed to compel Black men from the city of Philadelphia to enlist in the Union Army.

In the summer of 1863, General Robert E. Lee had invaded Pennsylvania and the most brutal war ever fought on American soil was at an inflection point. Most of the signatories on this historic piece of ephemera were a who’s who of Philadelphian free men (William D. Forten, Octavius Catto and many others), including Black ministers and educators who were committed to abolishing the Peculiar Institution—by all means available to them. Frederick Douglass also signed this historic call to arms, adding his weighty imprimatur to the broadside’s bullish message.

A framed print of the “Men of Color, To Arms! Now or Never!” broadside is installed just beyond the entranceway to the space that houses the Charles L. Blockson Afro-American Collection at Temple University. The Blockson collection is housed in Sullivan Hall on Temple’s campus. An architectural emblem of Temple’s classic collegiate status, Sullivan Hall is also home to the Office of the President. The building, and the Blockson collection in it, are both easily accessible from Broad Street, right along Polett Walk. The Charles L. Blockson Collection, in other words, is centrally located.

The general theme of the broadside is: this is your chance to take up arms and show all of the white racist supremacists what racial equality looks like in real time and in real life.

For Dr. Blockson, space matters, and according to him, space for archival collections is both at a premium and the primary consideration for sustaining his life’s work. He remembers a WHYY tour we did together on the occasion of the National Museum of African American History and Culture opening. “I’m 88 years old; I remember everything. I’ve been collecting since before you were born.” I have to laugh at this. It’s true, of course, but it is also exactly what I was looking forward to in talking with the man behind the archive.

When I want to talk more with him about his life, he tells me his voice comes and goes (he’s recovering from a cold when we speak) and directs me back to his archive, his books and his curator, Dr. Diana Turner. He’s been at Temple since 1983. “Have you been down to the collection?” he asks me. Of course, I have. He tells me about his most recent archival acquisition. “I received 39 items from the Harriet Tubman Collection”—all of which he donated to the NMAAHC.

The unrealized promise of freedom

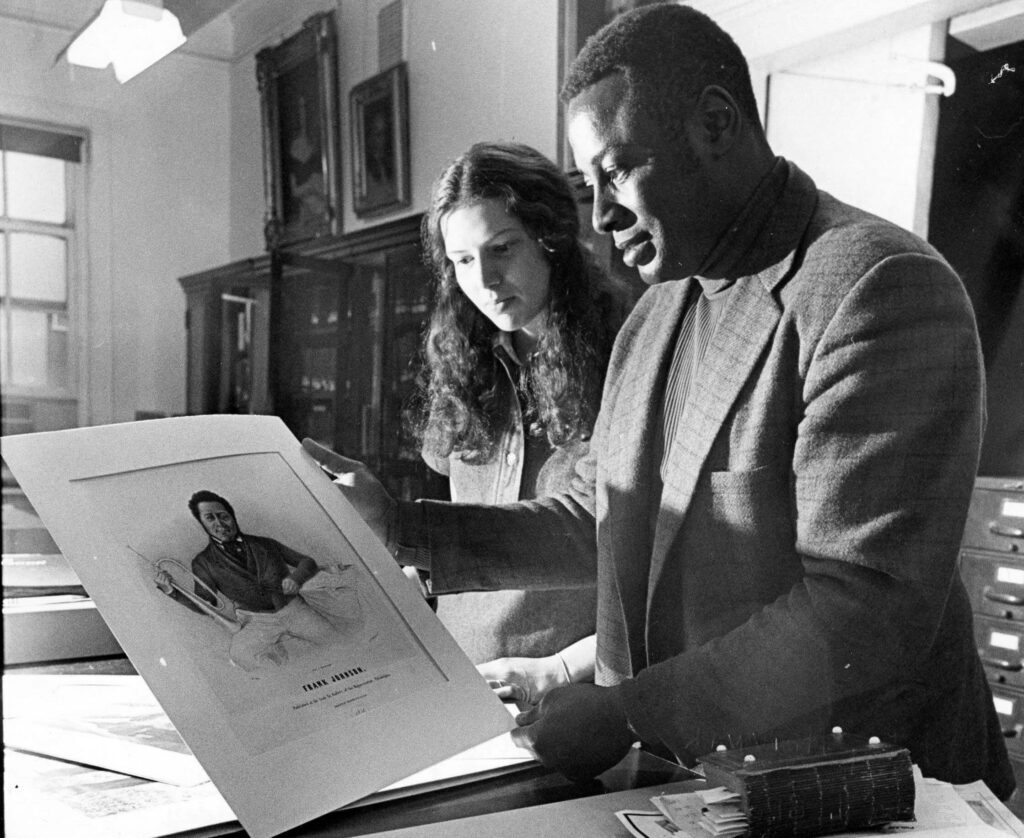

Almost 40 years ago (1984), Dr. Blockson donated his collection (over 500,00 items) to Temple University. The collection consists of but is in no way limited to first editions (from W.E.B. DuBois, Phyllis Wheatley and others); letters and correspondence from (and between) Black leaders, scholars, writers, and revolutionaries, the John Mosley Collection (an assortment of materials chronicling Black life in Philadelphia), and Paul Robeson’s sheet music. It is a world-class archive dedicated to gathering and curating the material artifacts of Black life. The full catalog of the archive stretches from 1581 into the 21st century. It is a monument to the lived experiences of Black people and an urgent reminder that this history was systematically erased and, thanks to Dr Blockson’s life-long commitment, it has been restored.

Blockson, an author in his own right, writing, editing and/or publishing 13 books, is an expert on the Underground Railroad and the history of Pennsylvania. He started collecting at an early age, coming up in Norristown, PA when the idea of an African American archive installed at a major research institution was just that – an idea. The “Men of Color, To Arms! Now or Never!” broadside is one powerful piece of history amongst hundreds of thousands. It is a striking document, partially because of its fearless clear-eyed call to arms and its implicit suggestion as an operating impulse for Blockson’s work. “This is our Golden moment . . .,” it begins.

The missive promises that if Black freemen rise up now and join the Union army; if they “STRIKE NOW,” they will secure their freedom forever. Note well here, that the promise of our forever freedom has not quite been realized. The signatories on this broadside would be amazed by our progress as a nation, but they would also be disappointed in the insistent residue of white supremacy that continues to dog our democratic experiment. The struggle continues. As such, the moral core of this broadside is complicated. It asks Black men to join White men in the Union—an exercise within which they will be treated as second/third-class soldiers—but the tone of the call is also unabashedly empowered.

The signatories on the broadside suggest a united front, calling on “all able bodied” Black men to join the liberation struggle. In history, this broadside was four by eight feet, more of a one-sided mini-billboard than a poster or flyer. The general theme is: this is your chance to take up arms and show all of the white racist supremacists what racial equality looks like in real time and in real life. It, in part, reads:

Our enemies have made the country believe that we are craven cowards, without soul, without manhood, without the spirit of soldiers. Shall we die with this stigma resting on our graves? Shall we leave this inheritance of shame to our children? No! A thousand times No! We WILL Rise! The alternative is upon us; let us rather die freemen than live to be slaves. What is life without liberty?

Before there were printed broadsides, the term “broadside” was nautical in nature and referred to firing all guns from one side of a warship in tandem. The “Men of Color, To Arms! Now or Never!” broadside certainly honors this etymology: The words on the page spit fire and freedom, but the call to arms was realized in the fight for freedom on the last battlefields of the American Civil War. There is a broader historical sense of irony for Douglass’s signature too, especially given the fact that he escaped enslavement partially due to his nautical knowledge and his sailor disguise.

The militant meanings of broadside shape the sensibility of the “Men of Color, To Arms! Now or Never!” broadside in the archival moment—when curators, museum goers, collectors, and journos enter a space to experience the palpable weight of Black history. This is the feeling that the Charles L. Blockson Afro-American Collection inspires.

“Think about your papers.”

When I ask Dr. Blockson about why it was important for him to collect broadsides, he almost cuts me off. “Anything that pertains to our history, I collected it; from postcards, books, pamphlets, broadsides, or whatever, even some records” he says. Archivists and collectors believe in the intrinsic value of all material culture associated with their subjects. This sense of intentionality comes across in every word that Dr. Blockson speaks.

“I miss my friend Harrison Ridley,” he tells me. “I think about him and the great collection that he had. It’s gone now. And there were other collectors before me, who were my role models—like Arthur Schomburg [of the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture at New York Public Library]; Paul Robeson, who was my main hero; and Marian Anderson. I met her, went to her home. I met Langston Hughes. I have a lot of heroes to follow—and a lot of their collections, their papers, their books are in the [Blockson] collection.”

In just a brief interview with Dr. Blockson I realize the ways in which he is a human repository for Black history. His collection is what it is: one of the greatest Black archives ever assembled. But he, himself, is a walking record of history. I ask him about the future of his legacy, about his inimitable contribution to history and the historical archive. “My main thrust now, my main thrust is more space, more space, more space for the collections. Because it is not only [for] my papers, or my collection.”

Blockson again directs me back to his published work. He reminds me that he published the first story written by an African American on the Underground Railroad for National Geographic magazine in July of 1984. Then he cuts himself off. “I don’t like to talk about myself because it’s all written.”

Given the prime real estate within which the Blockson Collection is installed, I am still curious about Blockson’s sense of urgency regarding archival space. “The space is not for me,” he tells me. “It’s for your papers. Where are your papers gonna go? Your life’s work; where’s it gonna go, brother? Think about it.” I realize he is not being rhetorical. He is actually challenging me to think about this in the midst of our conversation.

“I don’t know,” I say.

“No, think about it now,” he says. “You’re writing for a big paper. Think about it. You can encourage some person you don’t know . . . who is yet unborn. Your work is very important. Think about your papers.”

The call for space dedicated to archival work and historical collections is exceptionally compelling coming from the greatest (Black) archivist in Philadelphia’s history. But that call is not meant for me only. Dr. Blockson is also asking you—all of us—that same question: where are your papers, a record of your life’s work, going to go?

![]() RELATED

RELATED

Charles Blockson in 2017. Photo by Bruce Turner