My attention has recently turned to the profound macro forces that are reshaping our nation and the world. As an urbanist, I am interested in the interplay between the macro and the metro and the ways in which large, disruptive transnational forces (e.g., rising tensions with China, the existential threat of climate change, the accelerated pace of technological advances, the dissembling norms of democracy) come to ground and affect the shape of communities and the lives of people.

As Jacob Flores and I wrote last month, it is incumbent upon city and metropolitan leaders to understand these macro shifts so that they can navigate complex and often chaotic change on behalf of their communities. I will return to this theme many times over the course of the coming months.

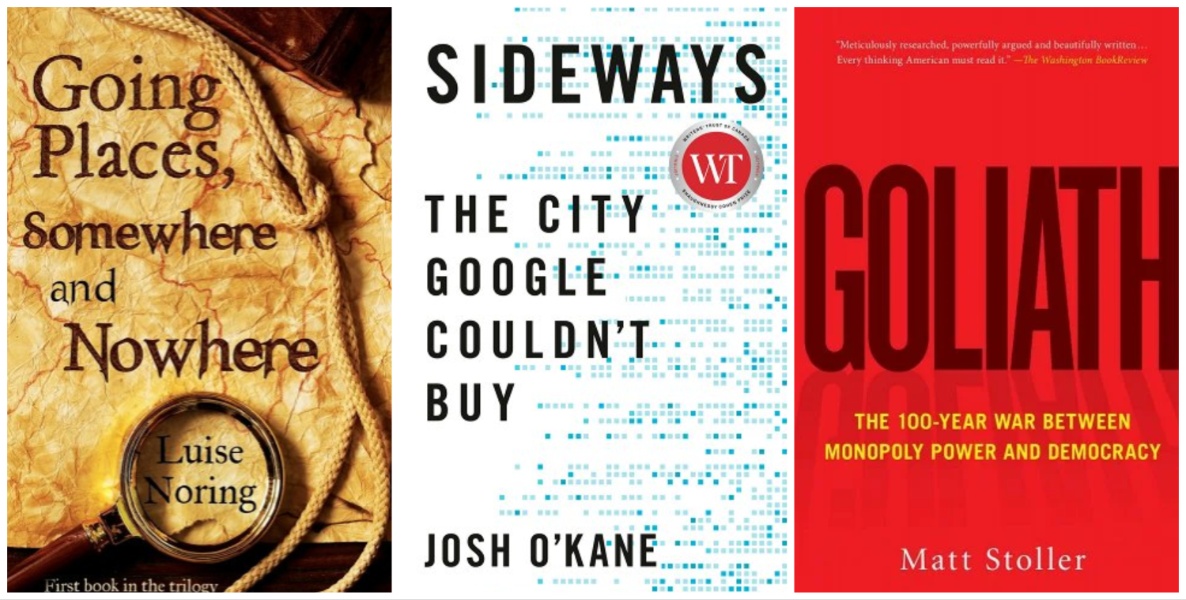

Making sense of a period dominated by poly-crises is never easy. I have always turned to books, and particularly histories, to make sense of a nonsensical world. I finally found a little time over the summer — freed from the daily clog of zoom calls, in person meetings, increasing travel and excessive Netflix binging — to turn to a series of books for illumination. I’d like to recommend three books — two nonfiction, one fiction — that fit the tumult of our times. They help explain the seismic changes we are experiencing, place them in historical context and offer a path forward. Only one of the books is ostensibly about cities, but all provide lessons for city builders to absorb and reflect. Hopefully, this will be the start of a mini-book club.

Goliath: The 100-Year War Between Monopoly Power and Democracy, by Matt Stoller

In the summer of 2019, Ross Baird (a friend and occasional co-author on this platform) gave me a copy of the galleys to Goliath before it was officially published. At the time, Ross and I were exploring ways in which committed entrepreneurs and creative financiers could come together to repopulate historic commercial corridors with locally based businesses, replacing vacancy with vibrancy. Ross implored me to read this book for a simple reason: It was impossible to make progress today without understanding how once great avenues of local commerce, vehicles for creating community wealth, were systematically destroyed by policies made long ago.

In a technology-saturated world, the most powerful role of cities, supported but not dictated by technology, must be to reimagine what it means to be a citizen-led democracy.

In Goliath, Matt Stoller explores how our economy and society came to be dominated by large, monopolistic firms which concentrate economic power, curtail competition, undermine democracy and hasten the fracturing of societies. With excruciating detail which spares no political party, Stoller reminds us that the current landscape of the U.S. economy is not inevitable but has been shaped and cemented by government policies. As he concludes, “Amazon, like Google and Facebook, exists because of the legal shift enabling and promoting bigness in structure and monopoly in business strategy.”

The book revives the detailed history of a mid-20th-century populism, led by Texas Representative Wright Patman, which not only extolled the virtues of small businesses but enacted laws and created oversight agencies which strove to create a level playing field between large conglomerates and local merchants. These historic battles have relevance to such present-day realities as the proliferation of low-quality Dollar Stores and their ilk in rural and urban commercial corridors alike and the persistent favoring of large firms over small as government procurement spending amps up in the aftermath of the pandemic. These battles also provide a useful backdrop to the current efforts to reinvigorate antitrust enforcement in the United States.

Goliath, like all good histories, presents and interprets the past in ways that point us towards a different future. Stoller is a prolific writer and blogger and I highly endorse subscribing to his Substack BIG.

Sideways: The City Google Couldn’t Buy by Josh O’Kane

In many respects, Sideways continues the story started by Goliath. In 2015, Google established a subsidiary called Sidewalk Labs with the goal of creating technologies that could help cities become safer, healthier and more efficient. They recruited Dan Doctoroff, the former deputy mayor of New York City under Mike Bloomberg, to run the company. Ultimately, the firm expanded its horizons to bid for the development of a portion of the Toronto Waterfront. Josh O’Kane, a reporter with the Globe and Mail, chronicles what happens next, a series of missteps and mishaps which brought to the fore serious concerns over data governance and privacy and illustrated how cities, in their own messy ways, manifest citizen democracy at its most fundamental.

Ultimately, Sidewalk Labs withdrew from Toronto and the firm was folded back into Google. On one level, the book captures the conflict between the hubris of big tech and the wizened big city. The book also provides a masterclass in how modern cities are governed, shaped by intricate power relationships between government, corporate, civic, and community actors. This is the stuff of drama, populated by outsize personalities and grand ideas, all compressed into one relatively small piece of urban real estate. To this end, I was not surprised to hear that the book is the basis for The Master Plan, a new satirical comedy by Michael Healey, now appearing on the Toronto stage.

For me, Sideways brought back several memories, one of a gathering that Sidewalk Labs held in New York City in the early days of the company and, the second, of a visit I made in late 2019 to the waterfront district as part of a larger trip to Toronto.

The early gathering brought together Google leaders (Larry Page bizarrely communicated to participants via a moving robot) and an eclectic group of urban thinkers, architects, planners, practitioners and officials. The heady goal was to discuss how the marriage of technology and cities might enable breakthroughs in the design of quality, sustainable places and the integrated delivery and management of housing, commerce, innovation and transport, energy, digital and water/waste infrastructure. At the time, Sidewalk had not settled on Toronto as the target of their ambitions, and I was intrigued that the company might even choose a city like Detroit to test early ideas and prototype new solutions. That is an alternative history of what might have been but market prices being market prices it was not to be.

When I did visit the Sidewalk Labs outpost in Toronto, the narrative had already shifted fast from what was possible (the creation of a new sustainable city powered by technology) to what was threatened (the loss of individual privacy). I admit that I came away impressed by Sidewalk’s deep, imaginative work on the interplay between urban buildings, transportation, water, energy and waste and believe that cities, now faced with the imperative of transitioning at speed and scale to a net zero future, would have benefited greatly from innovative practices and integrated strategies that never came to fruition.

Going Places, Somewhere and Nowhere by Luise Noring

I have left the one novel for last because I feel that fiction may be best suited to fully capture the utter disorientation of this moment. I have long been drawn to “journey” literature, where the protagonist travels the world encountering new lands, eccentric characters and hard challenges. I lost myself in The Phantom Tollbooth as a child, The Odyssey and Tolkien’s Middle Earth novels as a teenager, and Mark Helprin’s A Soldier of the Great War (and so many more) as an adult. These books transported me to other worlds, fueled my imagination and stayed with me for months if not years.

The debut novel by Luise Noring fits within this genre. Going Places is a fast-paced read, a futurist adventure that takes us from the U.K. to Latin America to the U.S. border to Asia. It tells a compelling story about a middle-aged woman and her twin daughters who find themselves struggling to survive against the backdrop of a third world war. The war is initiated not by nation-states but by the rise of online communities or factions that share common beliefs that transcend nations. Hostilities, once safely confined to the internet, spill over into the real world. As the story evolves, the algorithms of online communities play an increasingly important role. The algorithms feed on the online communities, but they also permeate the lives of declared factioneers. At a narrative plot level, the story is about how these women survive and how, as their paths separate, they embark on different journeys and live out different destinies.

Going Places is written against the backdrop of two global events: the devastating war in Ukraine and its random, senseless carnage, and the triumph of personally invasive and socially divisive technology that organizes communities in ways that undermine societal cohesion. This is a different kind of future state.

The global future that Noring imagines is dystopian, disturbing, disorienting, and utterly believable. Her description of warring factions that emerge from online communities and transcend national borders may be where the world heads.

The book paints a radically distinctive vision of a third world war and the personal courage it will require to survive. Rich in imagery and almost cinematic in quality, Going Places captures the mood of a world once again ravaged by war, conflict and technological threats. The renderings and maps are exquisitely drawn.

Going Places is intended to be the first in a trilogy. I eagerly look forward to reading the future installments; perhaps Noring’s fictional world may offer some hope for our real one. Here is a link to the author’s website which offers reviews, readings, character insights and a preview of the sequel.

One final note about Going Places: Although not a book about cities, readers of this column may recognize Luise Noring’s name from the multiple contributions she has made to scholarly literature on the ability of innovative urban institutions (e.g., Copenhagen City and Port) to unlock the present and future value of publicly owned assets for inclusive and sustainable regeneration. This work is more important than ever as cities struggle with structural housing and other crises.

On common themes

As readers will surmise, I managed to select, with little aforethought, three books with much in common. They all explore, in radically distinct ways, how the promise of technology to foster progress and connectivity has instead further fractured our societies, engendering distrust, disinformation and, in Going Places, utter societal dissolution. If anything, these books have encouraged me to delve deeper into the question of whether cities — the communal bonds they engender, the collaborative projects they enable, the real-world encounters they demand — might be the natural antidote to the on-lining of society. In a technology-saturated world, the most powerful role of cities, supported but not dictated by technology, must be to reimagine what it means to be a citizen-led democracy.

What’s on my night table

It is difficult to return to the normal Covid/post-Covid daily grind of Zoom calls once re-bitten by the book bug. I am currently preparing to dive into three books with the aim of deepening my understanding of environmental sustainability, governmental functionality and democratic vulnerability. These books are: Earth Transformed: An Untold History by Peter Frankopan; Recoding America: Why Government is Failing in the Digital Age and How We Can Do Better by Jennifer Pahlka; and 1923: The Forgotten Crisis in the Year of Hitler’s Coup by Mark Jones.

Bruce Katz is the Founding Director of the Nowak Metro Finance Lab at Drexel University.

![]() MORE FROM BRUCE KATZ

MORE FROM BRUCE KATZ