An apologue is a moral fable, a story, usually told with animals serving as characters. The allegory of the tortoise and the hare is probably one of the most conventional apologues. It tells the story about a race wherein the rabbit seems to have the advantage. Rabbits are fast; turtles are slow. But in this fable, the turtle wins because it runs steadily and deliberately. It’s a famous fable with a counterintuitive (moral) message: “Slow and steady wins the race.”

This rings true regularly in the real world, even through the ages of information, digitization and instant gratification. This well-known apologue is also an appropriate analog for how we might wrestle with the various forms of violence that continue to plague our city (and the rest of the world).

Violence moves at a frighteningly fast pace. Every day there are more shootings, more killings — more murder. Philadelphia police respond to more than 100,000 domestic-related 911 calls each year. Death by overdose was designated a public health emergency for the City of Philadelphia in 2021. The problems/challenges that shape our violent realities are multifaceted and inherently mercurial — poverty, access to guns, drug-flooded streets, limited economic opportunity, and the deliberate erosion of the city’s affordable residential infrastructure.

Helping the unseen be seen

The solutions for our violent reality are slower and much more difficult to identify and implement. This is where The Apologues Center, founded in Philadelphia by Zarinah Lomax in 2018, is making an important intervention. Apologues has a mission to tell the stories of survivors, especially survivors of gun violence, substance abuse, and domestic violence. Stories matter. And too often in the running-count narratives of violence in our communities, the names, faces and lived experiences of survivors are lost in the coverage.

“I started [The Apologues] to help people that felt unseen know that they were not,” Lomax tells me.

Lomax, the host of an arts television program on PhillyCam, initially asked survivors to come on her show to tell their stories. But not everyone was willing to step into the storytelling space following what was at times a mortal tragedy. “It was too vulnerable,” she says.

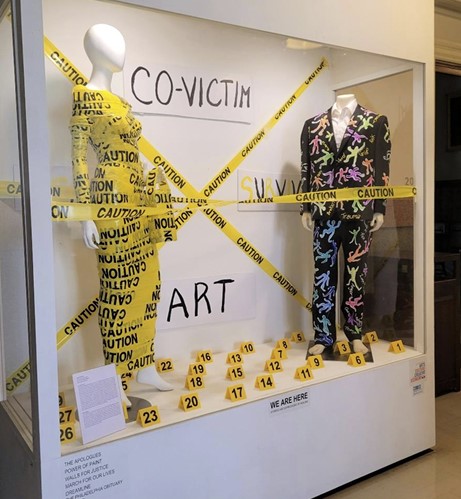

Then Lomax made an important pivot. She continues to host her show, but The Apologues operates in the artistic realm, creating space (and providing platforms) for survivors to experience visual art, photography and fashion, in honor of and in tribute to those whom they have lost, or for their own enduring commitment to overcoming trauma.

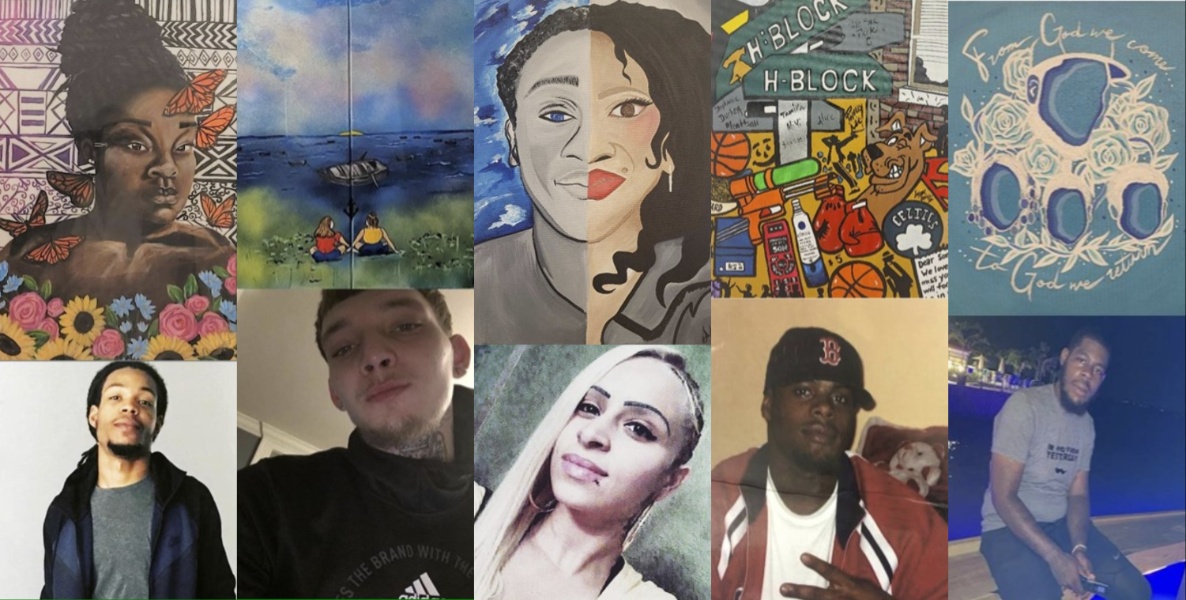

Lomax’s signature work has been a traveling community-centered installation that has had multiple stints at City Hall. The Apologues sources local artists to create murals dedicated to victims of violence and then provides programming and art therapy to community members wrestling with grief and the kind of loss that accrues to the families and survivors left in the wake of unforeseen tragedies.

“I basically wanted to humanize the emotions of what our community was going through,” Lomax says, “humanizing the people that were dying in the first place, because they give the names, but they’ll never show the faces. Like, you don’t even really know who these people are; you don’t know what happens to their families. Nothing. It’s just in and out.”

Art that celebrates those who have been lost

The Apologues programming is realized in a variety of ways. Lomax teaches wearable art classes, working directly with students to share her own infectious energy about the power of art to heal and inspire. She hosted several art exhibits and community conversations in April and May of this year. And, she was featured (along with The Apologues) in the Charles Foundation’s Youth Violence Prevention & Trauma Recovery Summit at Girard College.

The work of the Apologues to address the challenges of violence and survival in Philadelphia actually isn’t that slow, but it is definitely steady. On July 15, Lomax presented The Apologues in Germantown, including an art exhibit, live painting and a community conversation about gun violence. Artists presenting that day included Philly’s Queen Picasso and Desiree Norwood.

Lomax is more of a fashion designer than a visual artist, but she works with artists and surviving family members to conceptualize and design all of the work featured in The Apologues programs.

These programs create space for family members to experience art in the community that often celebrates the lives of those lost. Each piece of art or fashion is an apologue in and of itself. It tells a story about a loved one lost and points to the moral responsibility of our community to sustain its commitment to redressing violence in all of its forms, by all means necessary.

Through this work, Lomax started to address the grieving processes that family members, friends and the community endure through the kind of gun violence that a city like Philadelphia deals with daily. For Lomax, these survivors — those not directly impacted by the violent incident — were in fact “co-victims.” They needed to tell their stories too.

Co-victims include “anybody that is attached to or knows the person who may have passed away,” she says. “Because these are people that they don’t put faces to; when one person has died that person might be real popular, but you don’t really see outside of the immediate family, you don’t really see nobody.”

Still healing

Nobody knows this better than Lomax. She was conscripted into this work from her own experience with survival and co-victimhood as a rape survivor. Lomax has survived her own journey through substance abuse and the sexual violence she endured in the early part of her life. She ultimately turned to God and her faith. She was ordained as a minister in 2017. Lomax was also close friends with Dominique Oglesby, a 23-year-old student who was shot and killed in West Philadelphia in 2018, just months before she was scheduled to graduate from college.

“She did everything you wanted your child to do,” Lomax says, “just very smart; always excelled academically. So, it was really a shock for us; she just didn’t live that life and she had just come home from school.” Oglesby’s death was a devastating loss for Lomax, and for all of the media coverage of the shooting and the events leading up to it, there was no place for — no platform — for people to properly grieve and/or celebrate Dominique’s life. So, Lomax made one.

The Apologues has garnered some of the attention it deserves. Lomax continues to curate programs at City Hall, and local Philadelphia media outlets have covered some of the programming. Lomax is also in talks with various regional political leaders to continue to do what she does: Create space and place for survivors and co-victims to manage the pain of unimaginable loss, sometimes through the arts, sometimes through fashion and always through fellowship.

“I’m still healing now,” Lomax says. “You will be healing until God calls you home. There is no arrival moment. You just begin to be on the other side of what this is so you can be a survivor. I’m a survivor for the rest of my life.”

![]() MORE ON VIOLENCE, HEALING, AND ART FROM THE CITIZEN

MORE ON VIOLENCE, HEALING, AND ART FROM THE CITIZEN