I never thought I’d have a child, so I never thought I’d watch Sesame Street ever again. But in the past six years, I’ve had three children and watched it 9 million times. The episode we’ve watched the most is from 1978, titled “Naming Barkley,” when the whole gang picks a name for that big dumb orange dog. (They named him Barkley.)

When I first rewatched it, I was shocked by how much I remembered: Herry monster. John-John! Those purple, honking space sloths. That funky, slinky “1-2-3-4-5 …” song with the pinball animation. The one where the stoop kids rescue their toy jack with a horseshoe magnet. I was transported back to a time I’d long forgotten.

I was four years old when this episode came out, which, according to the brain trust of the Children’s Television Workshop, is the ideal age for me to retain this stuff.

This episode’s human actors were my childhood crew: Maria. Luis. Gordon (the second one). Weird Bob. Susan. Olivia. Ah, man — Mr. Hooper.

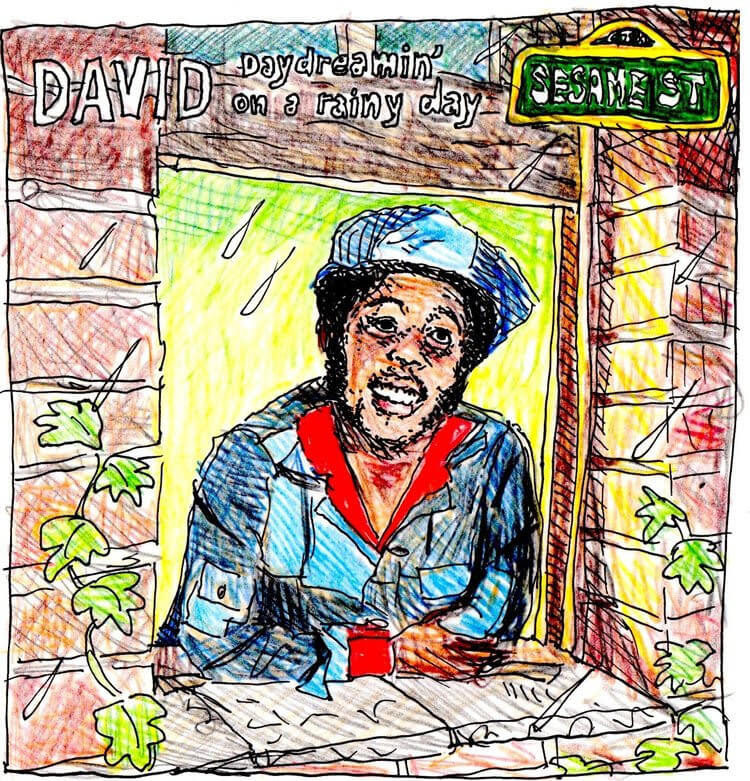

And David. I forgot about David. He was one of my favorites.

It only took a couple of rewatches before I Googled and rabbit-holed through the entire cast and was heartened that almost all of them were still alive, and that they also proudly spent the bulk of their careers as Sesame Street humans. You can find quotes from any of them proclaiming it as the best gig an actor could ever hope for. A once-in-a-lifetime opportunity! A wonderful journey! That sort of reverent enthusiasm. All except for David.

David was played by Northern Calloway from 1971 until 1989, but he died in 1990. The brief Wikipedia synopsis at the top of his page shocked me: “He was a favorite among the many viewers of Sesame Street during his time on the show, but a serious decline in his mental health increasingly hampered his later career until he had to be dismissed from the show. He was institutionalized and died less than eight months after his last appearance on the show.”

Those old episodes lost their magic for me after I read about David. Yet, I wanted to know more about what happened to him.

In 2008, an author named Michael Davis wrote Street Gang: The Complete History of Sesame Street, and significant portions of the book’s reporting were used in the 2021 documentary of the same name. The documentary focuses more on the show’s halcyon days, its societal impact, and Jim Henson’s magical puppetry. It’s a decent documentary, but I was uneasy waiting for them to mention David — or not mention David, rather.

There were a few clips of him during different set pieces here and there, but he was never named. He was listed in the credits as part of the “Humans of Sesame Street.” A small acknowledgment, but he was basically erased.

Because if they did mention him, they’d have to talk about this part, which I’ll summarize from Tennessean newspaper reports and sections of the Davis book:

On September 14, 1980, Northern Calloway was in Nashville to participate in a performing arts festival. While there, he’d picked up and quickly shacked up with 27-year-old Mary Stagaman. (According to many who worked closely with Calloway, this was a frequent occurrence.) But on September 19, he completely snapped.

According to the Nashville police report, Calloway beat Stagaman with an iron rod, then he fled her house, wearing only a tee-shirt, and proceeded to terrorize the Green Hills area of the city. He smashed a rock through a car window, destroyed some expensive crystal at another person’s home he had entered, stole a book bag from a young kid, ran into another person’s backyard, sat down, and ate fistfuls of grass.

When the cops came, he was hiding inside another family’s garage, bug-eyed and screaming, “I’m David from Sesame Street!” He told the police officers trying to subdue him that he was with the CIA and needed to speak to President Jimmy Carter.

Calloway dodged jail time because he pled temporary insanity and was allowed to return to New York under medical supervision. Stagaman spent two months in the hospital due to her injuries and sued him for $750,000, but it was settled out of court in 1982, just two days before it was set to trial. One of the police officers on the scene told the newspaper that Stagaman’s injuries were horrifying and it was a miracle that she survived. “He beat her so hard with that iron, it tore the iron up.” Details of the settlement were never revealed.

The tabloids mostly overlooked the story, but the Sesame Street higher-ups did not. Given the disturbing nature of what happened in Nashville, the Children’s Television Workshop agreed Calloway had to be fired immediately. However, there was an executive producer named Dulcy Singer who pushed back. And here’s where I’ll quote directly from what Singer said in the oral history because this blew me away:

“After the incident in Nashville, I had a hard time with the front office, convincing them we should keep Northern on the show. But it was apparent to me that he was extremely ill, so I fought to keep him. You don’t fire people because they are sick.”

I was stunned. I didn’t know that humans were capable of that level of compassion.

It also brought up so many bad memories for me. I’ve fired so many people before and after I read this I wrote the names of everyone I could remember — including those that could be safely categorized as “layoffs” — and counted 18 people, give or take a couple. I either sat down with these people face-to-face or had awkward shaky phone calls that usually lasted less than three minutes. I told myself these were business decisions and not human ones. I never pushed back against my bosses, even when some people didn’t deserve to get canned. My decisiveness in these moments — my ruthlessness — made me an excellent manager. I truly believed that at the time.

One time I fired a young guy who’d just had a baby. We met after work at a tapas bar near our office. I told him what was happening, and he stared through me for a few seconds. He was terrified and breathing heavily, waiting for me to blink or offer condolences or severance or a handbook about what he should do next, but I did no such thing. Eventually, he pushed away from the table, and it teetered, rattling the water glasses. He threw open the door and walked out. I ordered a drink to celebrate my job well done.

I feel sick and cowardly even thinking about it.

Northern Calloway vs. David

Northern Calloway not only survived the Nashville scandal, but he lasted nine more seasons. NINE.

He was prescribed lithium, and Singer kept close tabs on him to make sure he was prioritizing his health and seeing his psychiatrist regularly. But in 1982, Will Lee, who played Mr. Hooper, died unexpectedly.

The documentary honed in on this moment and the extraordinary challenges it presented to the show. It was decided that Mr. Hooper would not retire abruptly and move someplace far away and sunny. Will Lee died, so Mr. Hooper would also die. Sesame Street wanted to use this as an opportunity to teach kids about death, even though it was sad and scary.

I had aged out of Sesame Street by that point, but I have hazy memories of the significance of the “Farewell, Mr. Hooper” episode. I watched it again, and it is shattering: Big Bird is looking for Mr. Hooper so he can give him an illustration he drew, but then, one by one, each human on Sesame Street tells the heartbroken puppet bird that Mr. Hooper’s dead and never coming back. Big Bird doesn’t get it. “But I want him to come back!” Big Bird’s voice cracked, and my throat got tight. Big Bird repeatedly asks why it must be this way – why can’t Mr. Hooper return? “Because,” says Gordon. “Just because.”

And David decides to put off law school to run Mr. Hooper’s store. He promises to make Big Bird birdseed milkshakes just like Mr. Hooper used to.

But Calloway deteriorated gradually. He started doing coke along with the lithium, which led to more psychosis. There were more work-related incidents, too. One time during an argument with the musical director, Danny Epstein, Calloway bit him on the hand. And things got scary when a new teenage cast member named Alison Bartlett came on board to play Gina, an aspiring actress who worked alongside David in Mr. Hooper’s store. According to “Street Gang,” Calloway mentored her, and she adored him, but one time he showed up at her high school and proposed to her. They were no longer allowed to be on set together anymore. She forgave him, though.

Some of his cast members weren’t as kind and became frustrated with Calloway. The lithium made his weight fluctuate and he was very disoriented and on some days he would flub and slur his lines. One time he went on camera with potato chip crumbs on his face.

So Singer had to let him go. Accompanied by a psychiatrist, she took him to a restaurant and fired him. He was sad, but he understood. Dulcy Singer had done enough. David’s last episode was May 20, 1989.

A new character named Mr. Handford appeared on November 20, 1989. Alison Bartlett cheerily turns to the camera and explains what happened to David. “See, David doesn’t live here anymore. He went to the farm to live with his grandmother. But before he left, he sold the store to Mr. Handford, so that makes Mr. Handford my new boss.”

Gordon also recited a letter David sent to Elmo:

Dear Elmo,

How are you? Living on a farm is lots of fun. The country is beautiful, the air is fresh and clean, and there are even more horses and cows than there are on Sesame Street.

Love, David

PS: Say hello to everyone on Sesame Street.

Unlike Mr. Hooper, whose character died with dignity, David was sent off to an imaginary farm in Florida. But in real life, Northern Calloway died at an institution in upstate New York.

Initially, the cause of death was unknown. A coroner’s report later revealed that he died of excited delirium syndrome (EDS), “typically diagnosed postmortem in young adult males, disproportionally Black men, who were physically restrained at the time of death.”

What does compassion look like?

I might be giving Dulcy Singer too much credit as Calloway’s savior. I don’t know her true motive, whether she feared lawsuits or public excoriation if she fired Calloway after the Nashville stuff. Maybe she didn’t like the optics of her being a white executive firing a young black man from a show with a stellar reputation for progressiveness and teaching children how to treat everyone with respect and love.

But I desperately want Dulcy Singer’s support of Northern Calloway to be an extraordinary feat of compassion — that there was this powerful woman in charge of the country’s most influential children’s show who decided to fight for him despite his potential for psychotic mayhem because she determined it was the humane thing to do.

And this was 1980! People who suffered from mental illness were usually considered deviants or monsters if they went public with it. And given the heinousness of Calloway’s Nashville incident, she could hardly be blamed for letting him go.

Oh, and by the way: the decision not to lie to children about Mr. Hooper’s death was also made by — you guessed it — Dulcy Singer. I want to extract some of the goodness from her heart and place it in my own — to become more thoughtful and less afraid, but I have ways to go.

I’ll admit this: Any time I walk my children around our very family-friendly Los Angeles neighborhood, I am always tense. The city’s homeless population is overwhelming, and we’ve had some incidents that have rattled me. One time while Julieanne was parked at a stoplight on the way to taking our son to school, a man tried to open the backdoor of the car where my son was strapped in the baby seat. Another time there was a man walking up and down the sidewalk outside our door late at night shouting truly vile and terrifying nonsense. “I’m gonna kill all you motherfuckers!” Things of that nature.

Some of our neighbors have formed a watch group, working directly with the police, encouraging everyone to speak up about “disturbing behavior” so a report can be filed. I used to be on the email list, but it did nothing but stoke fear and made me feel like a terrible human being. No one on the list wanted to help — they just wanted certain types of people to disappear.

But a couple weeks ago, an old woman was in the throes of distress, tearing up a book along our block. Her clothing was oversized and filthy, and after she’d shredded the book, she stopped to lie down on the grassy area between the sidewalk and the street. I walked outside and began to pick up the torn pages of the book that had floated into our flower bed, keeping a close, anxious eye on her. I didn’t want to call the cops, but L.A. has yet to fully integrate its social services hotline program so, instead, I did nothing.

This woman was there for at least an hour, not moving at all, the sun beating down on her. Eventually, a fire truck arrived, pulled up alongside her, and blasted its horn until she got up. The truck followed her as she walked to another side of the street, back to someplace less visible, so she didn’t make anyone on our block feel uncomfortable anymore.

What would the Sesame Street lesson be about these situations? Because I don’t know what to do. I consider myself a thoughtful, kind-hearted man but I know I’m failing when I’m afraid or feel threatened by people like the woman tearing up the book or by people like Northern Calloway.

And what do I tell my children? Because I don’t even know what I’m going to say to my children about me — about my struggles with mental illness, addictions, and darkness. I will try to be honest, but how do I do that without scaring them.

I wish there was a Sesame Street episode about this.

One last thing

In that “Naming Barkley” episode, one of the final scenes with the Sesame Street humans is eerie. David’s about to knock on Big Bird’s door, but he hears Big Bird talking to what he thinks is an imaginary friend — the brown furry elephant-seeming puppet, Mr. Snuffleupagus. But David hears two voices behind the door — Big Bird’s and another deeper and raspier one. He’s convinced this other voice is, in fact, Mr. Snuffleupagus.

David runs and gathers the rest of the Sesame Street humans and tells them what he’s heard. They’re skeptical, yet they’re taken in by his excitement and assurance that Mr. Snuffleupagus’s existence will finally be revealed. They follow him to Big Bird’s nest behind the door and walk into it, only to find … nothing there. Everyone’s annoyed, especially Mr. Hooper, who yells at David, “Are you alright?!”

The rest of the cast slowly walks out to scold and mock David for his wild imagination, his foolishness — his craziness. David hangs his head in shame and follows the others out the door. He hears the voice again. But thinks better of causing another scene. He puts his hands behind his back, whistles softly, and walks away.

A.J. Daulerio is the former editor of Deadspin and Gawker. This piece first ran in The Small Bow, his newsletter about long-term recovery.

![]() MORE CULTURAL EXPERIENCES FROM CITIZEN VOICES

MORE CULTURAL EXPERIENCES FROM CITIZEN VOICES