It wasn’t long ago that, in a Citizen virtual town hall, MSNBC’s Ali Velshi waxed inspirational on the role of the journalist in these fraught times: “We bear witness and hold power to account,” he said.

Just weeks later, there he was, a suburban Philly resident and Citizen board member, on the streets of Minneapolis, reporting live from a seeming war zone in the American city where George Floyd was murdered by police.

![]() When we spoke in March, Velshi reacted humbly when I called him an essential worker on the frontline of the pandemic; as expected, he cited cops and nurses and doctors as the true heroes. But here he was, weeks later, in harm’s way, getting shot with a rubber bullet by police on live TV, determined to bring into our living rooms the unrest on the streets and the often overly aggressive response of those who had sworn to protect and serve.

When we spoke in March, Velshi reacted humbly when I called him an essential worker on the frontline of the pandemic; as expected, he cited cops and nurses and doctors as the true heroes. But here he was, weeks later, in harm’s way, getting shot with a rubber bullet by police on live TV, determined to bring into our living rooms the unrest on the streets and the often overly aggressive response of those who had sworn to protect and serve.

See the harrowing footage here:

I caught up with Velshi on Sunday morning, after he’d been on air into the wee hours, chronicling the story of the killing of Rayshard Brooks by Atlanta police in the drive-thru of a Wendy’s, and the civil unrest that spawned.

He was driving back to Philly from New York for his son’s college graduation, and didn’t know yet whether, in 24 hours, he’d be on a plane to Atlanta to report from its streets.

“I’ve got my gas mask in my bag, in case I’m heading straight there,” he said.

What follows is an edited and condensed version of our conversation.

Larry Platt: That’s got to be a surreal experience — wearing a gas mask on a city street in America, and getting shot.

Ali Velshi: I never would have thought I’d be wearing a gas mask, a helmet and a bulletproof vest in America to protect me from the police. I’ll say this, I’m glad it wasn’t my eye. One reporter got shot in the eye and lost her eyesight. I got hit in the shin, pretty good.

I had all this adrenaline. I knew there was something whizzing around, and when I felt it, I thought I’d been shot, but wasn’t really sure. It felt like I took a hockey puck to the shin. It took a moment to register that I’d been shot. It hurt, but it hurt more over the next three days.

LP: Turns out, rubber bullets aren’t even rubber, and can be fatal. Years ago, they were used during The Troubles in Northern Ireland and 17 people were killed, which begs the question: While we’re talking about police reform, why are they used at all and why is it that police are not required to document when they use them?

AV: Great point. Trust me, this is not Nerf. “Rubber bullets” is a misnomer. It’s much worse than it sounds.

LP: So walk us through how you ended up getting shot?

AV: It was the night after the curfew was put in place. As the curfew was coming into effect, we were walking well behind the protestors. As we approached an intersection, the police and National Guard quickly split the crowd, and started shooting in both directions. The crowd dispersed to back behind me, so now we were right at the front. That’s when I got hit in the shin. We had our hands up and were yelling, “We’re media!” and the cops said back, “We don’t care!” and fired a second time, but didn’t hit us.

Those National Guardsmen were kids with big lawn guns. I’d always admired the Guardsmen who were deployed over the years to help their fellow Americans during hurricanes or natural disasters. I found myself really feeling for them.

The night before, they were sitting in their homes, minding their own business, ![]() and now they were being asked to do things they never signed up to do, holding guns on their fellow citizens. A lot of times, their hands were adjacent to or on the trigger. Protestors would yell, “Take your fingers off the trigger” and sometimes they would.

and now they were being asked to do things they never signed up to do, holding guns on their fellow citizens. A lot of times, their hands were adjacent to or on the trigger. Protestors would yell, “Take your fingers off the trigger” and sometimes they would.

LP: Wow. You really were reporting from a war zone. In fact, this was no isolated instance. There have been many documented cases of journalists being targeted by police.

“If you think I’m a threat, that’s a problem. Journalists are not a threat. We tell stories. This is why it’s so important that we as journalists earn the trust of the people. Because our right to do our job is your right to hear the story.”

AV: I’ve since said to colleagues, if we were covering this somewhere else, we’d be saying, “An authoritarian regime was silencing opposition and targeting media.” That’s what it felt like. That’s not the way it’s supposed to go here.

To all of us, this really felt like the natural culmination of three-and-a-half years of the media being portrayed as enemy of the people. Someone on Twitter said, “Well, you shouldn’t have been out after curfew.” But curfews don’t apply to media.

You and I have talked about this before — our job is to bear witness and hold the powerful to account. After I got hit, we were on the phone with my bosses and our security team and we considered just going back to our hotel. But I said we can’t — this is where the story is. We can’t bear witness from the hotel.

The Washington Post has that slogan ”Democracy Dies In Darkness.” This is part of what they’re talking about. The Darkness is if we’re back at the hotel. Because the people in power would love it if we’re not there to tell you what happened, if we’re not bearing witness.

LP: You’ve now reported from the streets of numerous uprisings, and I wonder if you’ve seen the left or right wing outside agitators driving these protests, as elected officials have intimated?

AV: I’ve reported from Minneapolis, Chicago and New York, and I’ve seen zero of that. I’ve covered organized marches in the past — with leaflets, registration tables — and these all feel like they’re the opposite of organized. It feels very spontaneous. I’ve seen more white people than black people protesting; I’ve seen folks marching with their dogs. In Minneapolis, I saw the setting of fires and looting, but that was by a minority of the crowd and even that felt like it wasn’t organized.

LP: When we’re so divided, over seemingly everything, how do you as a reporter try to maintain your credibility, when motive is called into question as a matter of course nowadays?

AV: I see the tweets accusing MSNBC of being part of the Resistance. Sometimes when you hold power to account, that can intersect with the goals of protest movements, and disentangling that can become complicated. Our coverage of the Muslim ban or immigrant kids in cages can be seen to be not indistinguishable from the protests of those things.

It’s complicated. If you believe, as you and I do, in civil discourse, it’s very hard in this time to stick to that principle when you’re confronted by things that look like right or wrong. To me, it requires always saying to ourselves that we’re either in the business of dialogue and bearing witness or we’re not.

LP: I was very bothered by The New York Times’ flip-flop on publishing an op-ed by a U.S. senator, and by The Inquirer’s jettisoning of its editor after a particularly tone-deaf headline. Seems to me, if you’re a media organization — if you’re in the dialogue business — your job is to respond to ill-conceived or offensive speech by producing better speech in the town square, no?

AV: That commitment to editorial principles solves a lot on the front end. The Inquirer thing did seem tone deaf, and a lot of white people are tone deaf. But Is there a middle ground between a mea culpa and a firing? I don’t know. We’re in a moment where not being a racist is not enough.

These are complicated questions, Larry. If you’re in the media business, you have to know what you stand for and what constitutes free speech. You know, for a long time we’ve carved out a type of First Amendment exception for hate speech. There’s a danger to having a certain type of hate speech elevated and validated.

“If you believe, as you and I do, in civil discourse, it’s very hard in this time to stick to that principle when you’re confronted by things that look like right or wrong. To me, it requires always saying to ourselves that we’re either in the business of dialogue and bearing witness or we’re not.”

LP: But then I think of Charlottesville — seeing those protestors march with Tiki Torches and chanting “Jews Will Not Replace Us” actually was important to stir the conscience of the land, I think. You didn’t say, that’s offensive, let’s not upset people by airing it.

AV: That’s a great example. Why would you run the video of Rayshard Brooks being shot and killed by police in Atlanta? Or the video of George Floyd essentially narrating his own death at the hands of police? That’s the bearing witness part. Because otherwise a whole lot of people don’t believe it. People need to see it to make their own judgment about it.

These are tough questions you’re asking about journalistic judgment, and I’ll give The New York Times and other media outlets this—like us, they’re asking these questions every day. That doesn’t mean you’re always going to get them right.

LP: You’ve done a great job of covering the protests, but I find myself worrying about what substantively comes of all this. Do you have thoughts on what this moment is giving rise to?

AV: There are several levels of substantive outcomes, I think. The first is the degree to which Trump’s mishandling of something is costing him. There are meaningful drops in his standing in the polls due to his handling of coronavirus and the policing protests. Obviously, the election will be the biggest chance for change, but it seems like he’s on the wrong side of history when it comes to police reform and addressing systemic racism.

A second substantive effect will be a return to state and local reforms. President Obama gave that address recently where he said that much of this work will have to be done at the state and local levels. That’s not as sexy—there are 18,000 police forces in America and no generalized agreement on use of force. But now you see New York, Seattle and Minnesota enacting change on chokeholds and the accessing of police records, and that’s important.

Third, this is already starting some meaningful discussions on the effect that police unions have had. For journalists like me, who have supported the aims of the labor movement, we have to shine a light on those unions that are all about keeping bad apples on the job. We are critical when teachers unions do that, and bad teachers don’t end up getting anyone killed. We have to say there is something wrong with police unions in this country.

“I’ve since said to colleagues, if we were covering this somewhere else, we’d be saying, “An authoritarian regime was silencing opposition and targeting media.” That’s what it felt like. That’s not the way it’s supposed to go here.”

Fourth, police have had their roles expanded over the years—just like schools have had to perform child care and feeding roles. Police roles have expanded into domains they might not have enough training in, like mental health and deescalation. Did police need to show up because a guy fell asleep in his car at a Wendy’s drive-thru? In the UK, most police don’t even carry weapons. Maybe that’s a model we should look at. But the point is that defunding the police is really a call to reimagine the role of the police officer.

![]() I don’t know if I ever told you this, but I was a volunteer with New York’s Department of Homeless Services. If you called 911 on someone who appeared homeless, they’d reroute the call to 311, which would reroute it to Homeless Services, and a social worker and a volunteer would show up.

I don’t know if I ever told you this, but I was a volunteer with New York’s Department of Homeless Services. If you called 911 on someone who appeared homeless, they’d reroute the call to 311, which would reroute it to Homeless Services, and a social worker and a volunteer would show up.

If there was a threat of violence, the police would roll up, too. But now you have psychologists intervening, providing services, and not the police. You’re saving someone from being arrested and put into the system which, by the way, is cheaper for society. Cops would be happy about that.

LP: I want to return to the police reaction, particularly as it applies to journalists. Because the First Amendment is really in jeopardy if police are regularly seeing journalists as an enemy combatant—which means Democracy itself is threatened. How bad is it?

AV: Reporting from the streets in New York, I heard on my scanner that police had arrested 12 white protestors for breaking curfew and they were sitting on a sidewalk awaiting transport. I got there, and the line keeping media back was further away than I thought it should have been. You’re supposed to be able to be as close as possible without interfering with official acts. So I asked one of the cops why we’re so far back. When he wouldn’t answer me, I asked again. And then another cop said if I asked one more time, I’d be arrested.

Really? For asking a question? If you think I’m a threat, that’s a problem. Journalists are not a threat. We tell stories. This is why it’s so important that we as journalists earn the trust of the people. Because our right to do our job is your right to hear the story.

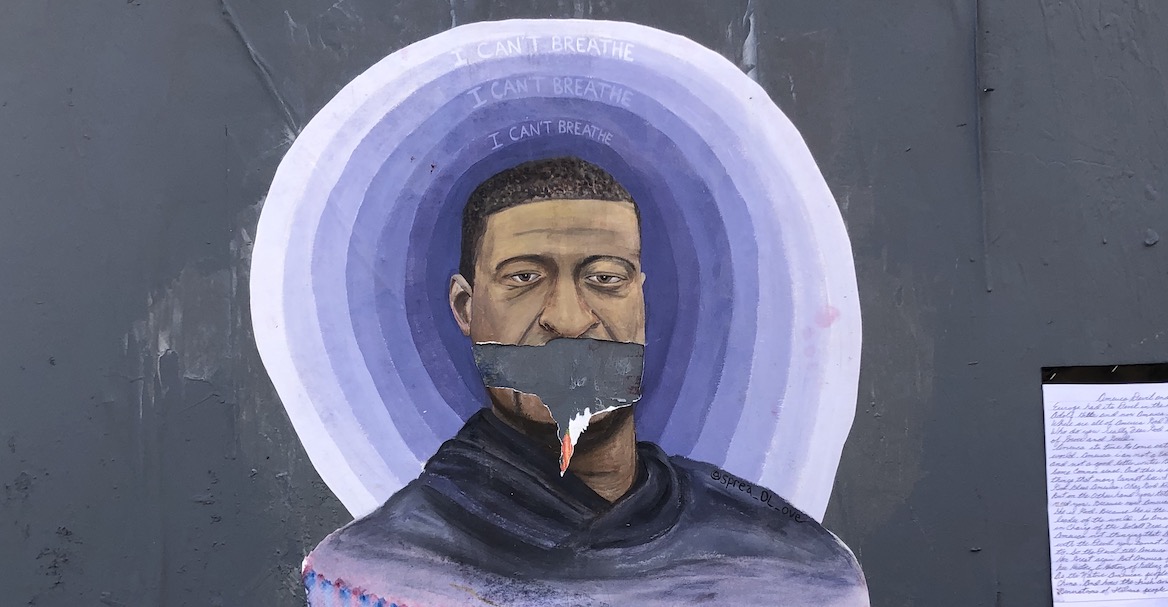

Header photo courtesy MSNBC