“Larry, where are you on Kaepernick?”

Uh-oh, here we go. I’ve known Charles Barkley for nearly three decades, and this is usually how it starts. We’re among a bevy of common friends in a bar somewhere—in this case, about two weeks ago, it’s a Mexican joint in Ardmore—and, never having an unexpressed thought, the irrepressible Barkley asks a seemingly innocent question when what he really wants is a debate. It’s part of what makes him such a compelling character on TV—he’s always asking questions and questioning answers.

“Well, as you may remember, I tend to support anyone who is exercising their First Amendment rights,” I said, hearkening back to the early ‘90s, when Barkley was sports’ preeminent bad boy and I wrote often about how he had something important to say. In fact, back then, Barkley was far more in-your-face than Kaepernick, who has refused to stand for the national anthem to protest police mistreatment of African-Americans. Back then, I was in the locker room the night Barkley lectured the white, male media throng with his unique brand of social consciousness: “Just because you give Charles Barkley a lot of money, it doesn’t mean I’m going to forget about the people in the ghettos and slums,” he opined. “Y’all don’t want me talking about this stuff, but I’m going to voice my opinions. Me getting 20 rebounds ain’t important. We’ve got people homeless on our streets and the media is crowding around my locker.”

Today, people forget that Charles Barkley. Like many of us, he’s grown, if not more conservative, then certainly more pragmatic. Through the years, during these nights out, Barkley’s witty insights have often called out my white liberal hypocrisy.

True citizenship is not a spectator sport. It requires work. How many of those protesting and how many of those self-righteously calling the protestors’ actions and motives into question have actually voted?

On Kaepernick, though, we were roughly in the same place. “I support his right to speak out, too, but I was talking to [NBA team owner] Mark Cuban about this the other day,” Barkley said. “I’m glad Kaepernick is putting some money where his mouth is and supporting some inner city programs, because I’m tired of protests without action. I’m all about solutions now.”

That’s why Barkley—though he doesn’t like it reported—has given away millions, underwriting academic scholarships for black and white low-income kids alike. And it’s why, among his many investments, is a company that blocks cell phone usage in prisons; he’ll cite chapter and verse of the dangers outside the prison walls that derive from illegal cell phones inside.

As the Kaepernick story has morphed into dueling ad hominem attacks—Black Lives versus Blue Lives—Barkley has grown frustrated. “Everybody’s screaming at each other,” he said. “I just want to figure out what works and argue about doing that.”

After our dinner, I kept thinking about Barkley’s words, especially now that so many other athletes have followed Kaepernick’s lead in kneeling during the playing of the national anthem. We tend to forget that, historically, sports has often been a driving force for social change. The civil rights movement, after all, actually began seven years before Brown v. Board of Ed, when Jackie Robinson crossed the color line. And it was Muhammad Ali’s pithy critique of the Vietnam War—“I ain’t got no quarrel with them Vietcong”—that helped fuel an anti-war movement. But after the activism of the 1960s, most sports stars—owing to the millions in endorsement deals thrown their way in the 1990s—ceased to speak out, culminating in Michael Jordan’s silence when a credible black candidate, Harvey Gantt, challenged racist Senator Jesse Helms in a North Carolina U.S. Senate race. “Republicans buy sneakers, too,” Jordan said when asked why he hadn’t endorsed Gantt in his home state election.

So it’s refreshing that athletes are now bold enough to wade in and help shape the American conversation, but I’m wondering if they can’t do even more. The conversation with Barkley has prompted a few random thoughts—and one notion for how we might constructively move forward:

![]() We need a higher bar for judging patriotism. Kneeling through the singing of a song, as well as sitting on the couch and questioning the patriotism of those who kneel, is relatively easy. True citizenship, however, is not a spectator sport. It requires work. How many of those protesting and how many of those self-righteously calling the protestors’ actions and motives into question have actually voted? How many not only know the names of their elected representatives, but have let said representatives know what they think about the pressing matters of the day? How many give money or time to advance the cause of racial and social justice in their own communities?

We need a higher bar for judging patriotism. Kneeling through the singing of a song, as well as sitting on the couch and questioning the patriotism of those who kneel, is relatively easy. True citizenship, however, is not a spectator sport. It requires work. How many of those protesting and how many of those self-righteously calling the protestors’ actions and motives into question have actually voted? How many not only know the names of their elected representatives, but have let said representatives know what they think about the pressing matters of the day? How many give money or time to advance the cause of racial and social justice in their own communities?

We need a tutorial on our own history. Here’s where we really owe Kaepernick a debt of gratitude; his act of civil disobedience has provided context and taught many of us about the origins of “The Star-Spangled Banner.” I’d always been vaguely aware that its composer, Francis Scott Key, had owned slaves, but, in the aftermath of Kaepernick, another Philly guy—Penn alum John Legend—linked in a tweet to a story detailing the song’s original racism. Apparently, there’s a third verse that we don’t sing [“No refuge could save the hireling and slave / From the terror of flight or the gloom of the grave”] that celebrates the killing of slaves who’d freed themselves and joined the British cause in the War of 1812. Now, you might dismiss this context as old history that is no longer relevant in 2016, but if we’re all going to genuflect en masse before sporting events and sing this song, shouldn’t we at least be aware of the etymology of the words coming out of our mouths?

The context leads me to agree with Legend, who suggests we should make “America The Beautiful” our national anthem. Or, how about this: Let’s replace Key’s divisive lyrics with “Lift Every Voice And Sing,” commonly referred to as the Black National Anthem, which, both lyrically and emotionally, is just a much better song.

We need to hold our public rituals up to conscious inspection. Why, after all, do we stand and sing any song before sporting events? When I go to a play or a movie, we don’t all begin by jumping up, hands to our hearts, and break into song together. It started when, in 1916, President Woodrow Wilson (whose come in for some criticism of late owing to his own racist past), ordered that the song be played at military ceremonies. During the World Series of 1918, a band played the song as part of the seventh inning stretch entertainment—and the crowd, already on its feet, sang along. A tradition was born.

That it has morphed into a litmus test on one’s love for country is absurd. The most common complaint lobbed Kaepernick’s way of late is that, by not standing for the song, he’s not supporting the men and women of America’s fighting forces. But aren’t there better, more constructive ways to support the troops? For example, if all those now complaining about Kaepernick had written to their elected officials during the Iraq War to tell policymakers that sending our troops off to battle with insufficient body armor was unacceptable, actual soldiers’ lives might have been saved.

Like Barkley, I’m more interested in actions that result in advancing the cause of justice in real people’s lives than in controversial photo ops. That’s why I was psyched to see Eagles’ safety Malcolm Jenkins in July—before le’ affaire Kaepernick—organize a group of players to meet with Police Commissioner Richard Ross and his team. “There’s an obvious need for reconciliation when you talk about those two communities,” Jenkins said at the time. “I wanted to see if there’s a way that we can break that ice and just start the conversation . . . and use the resources of the guys that’s in this room to help facilitate that.”

It’s actions like Jenkins’ that have the most problem-solving potential. According to Wharton’s Ken Shropshire, athletes have more power to effect positive social change than they know. That’s why he was instrumental in developing The Ross Initiative In Sports for Equality, or RISE, a nonprofit organization started by Stephen Ross, the owner of the Miami Dolphins, dedicated to “harnessing the unifying power of sport to advance race relations.” It grew out of headlines that engulfed Ross’ team in 2013, when offensive lineman Richie Incognito used racist and homophobic taunts in bullying a teammate. Ross disciplined his employee, but he reached out to Shropshire because he wanted to do more. Shropshire recruited bold face names for the board, like NBA superstar Steph Curry, and RISE developed curricula to use sports to teach tolerance and combat bigotry. They’re just getting started, but the animating idea is that sport actually punches above its weight, and that athletes can be instrumental not just in raising awareness, but also in shaping solutions.

That’s why I’m with the most unlikely philosopher prince I know, the dude who beat the crap out of Barney on Saturday Night Live. Let’s debate solutions rather than just point fingers over who is to blame for the problem.

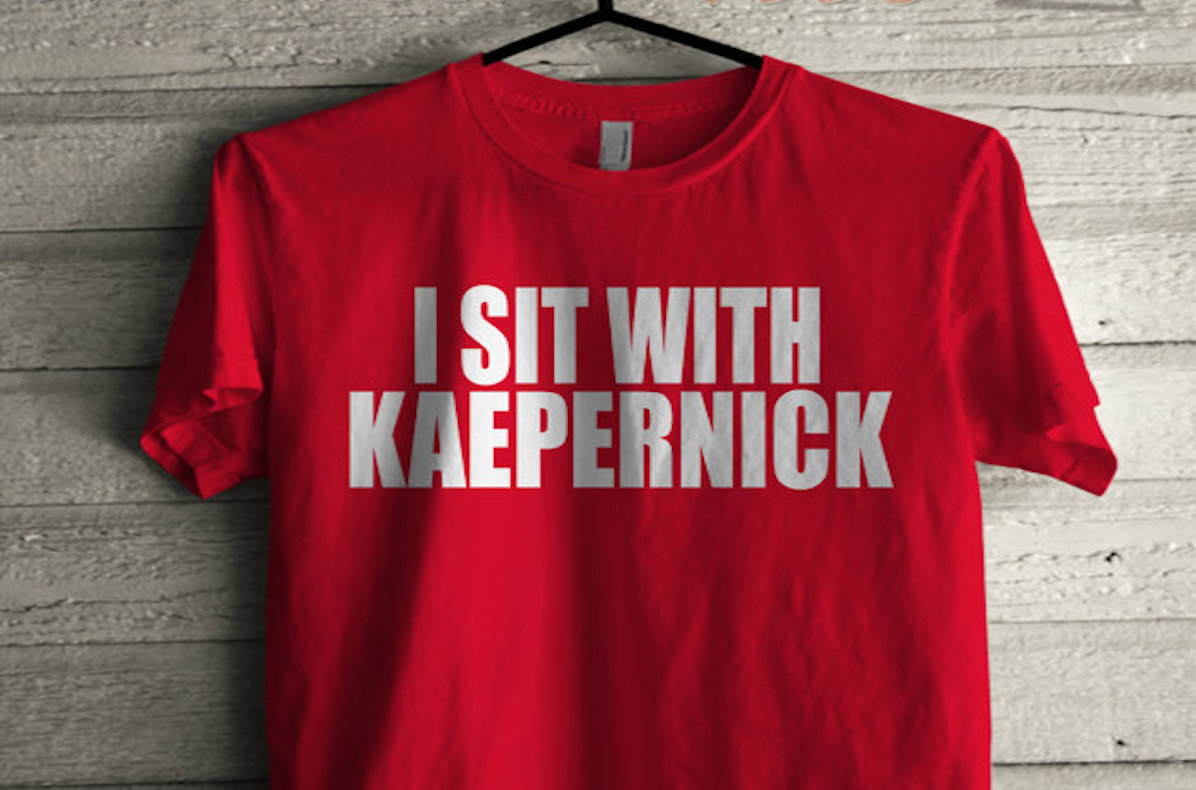

Header photo: T-shirt XpressionTees on Etsy.