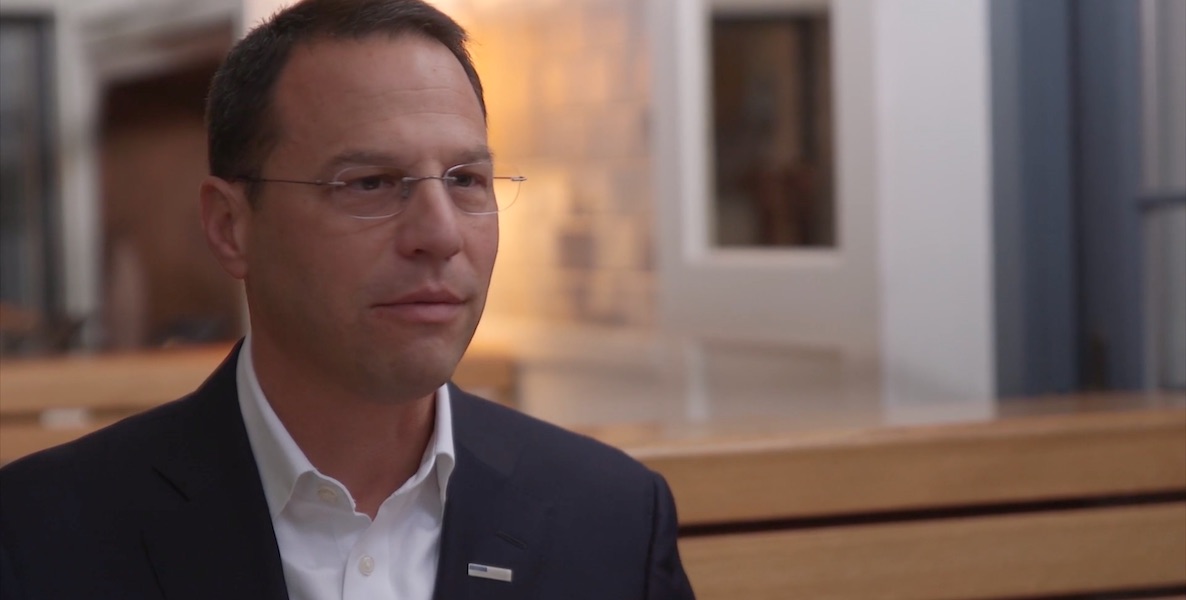

Way back on March 21st, Ajay Raju—Citizen co-founder, lawyer, philanthropist—was a guest on The True Philadelphia podcast, hosted by 6abc’s Matt O’Donnell.

While many of us in the media were still enmeshed in the daily stenography of the pandemic that has eaten the world, their conversation took a decidedly longer view. They talked about what the world might look like when the dust settles, and touched on some of the permanent changes this experience is likely to usher in.

As our quarantine has gone on, I found myself thinking more and more about the futurism of their conversation.

I later caught up with Raju about it. What follows is a condensed and edited version of that conversation.

Larry Platt: First thing first, how are you and the family doing?

Ajay Raju: I am adjusting to house arrest. We’re all home and healthy, thank God.

LP: Good to hear. Now, for the important stuff: what are you binge-watching?

AR: I’ve been revisiting The Sopranos. Uncle Junior’s house arrest arc is really striking a chord at the moment.

LP: I’d forgotten about that. You’ve mentioned that you feel this experience will forever change you. What do you mean by that?

AR: The truth is, life has gone off course but that doesn’t mean it’s necessarily gone off track. This crisis has really shed a light on how much of what we do, what we value, what we worry about and what we ignore, is entirely contingent on a set of conditions that are anything but permanent. Trying to understand what in this world is permanent, dependable and sturdy enough to build a foundation upon requires that we reconnect with ourselves and the people closest to us in ways that we couldn’t have conceived of under any other circumstances.

This future presents an opportunity to learn, to share knowledge and to make the world far better than it is today—or far worse. It all depends on who controls that trove of data, and to what end it is used. That’s the one thing we can’t predict.

LP: So, in that way, this is an opportunity to reconnect with our families and our values?

AR: Absolutely. For better and for worse, this is a revelatory moment in human history. We are going to learn that so much of what we take for granted actually matters profoundly and that so much of what we have always thought of as profound is actually meaningless.

We’re discovering new ways to engage with each other, with technology, and with each other through technologies. And it will be impossible to shove these discoveries back into the proverbial toothpaste tube.

![]() The example that most immediately comes to mind is the phenomenon of offices. If we think of contemporary office work as the kind of labor that is generally performed via phone and computer, then we seem to be proving to ourselves that maybe physical, brick-and-mortar office spaces aren’t strictly necessary, or even responsible from a public health standpoint.

The example that most immediately comes to mind is the phenomenon of offices. If we think of contemporary office work as the kind of labor that is generally performed via phone and computer, then we seem to be proving to ourselves that maybe physical, brick-and-mortar office spaces aren’t strictly necessary, or even responsible from a public health standpoint.

An assertion like that may have the skyscraper industry tugging its collars, but the fact is that we are in the middle of both an emergency and an opportunity to re-evaluate everything, and to realign our social habits and cultures with the realities of modern technology.

LP: That’s a great point, but this isolation has also proven to me how much we need social interaction. We’re social beings. This feels unnatural, and to the extent that technology makes it easier, are we moving toward a more alienated and isolated society?

AR: This is not to say that good old face-to-face interaction doesn’t matter, that humanity doesn’t matter. The internet and artificial intelligence may allow us to work from home, to video-chat with loved ones across the country, and to diagnose and treat disease far more quickly, but AI can’t speak to our souls, make us laugh, cry or think for ourselves.

Knowledge and content will be increasingly democratized but we’ll have to look inward as well. We’ll need to more intimately understand our minds and bodies. Mindfulness and empathy will become imperatives, especially as loneliness becomes more prevalent. And I know it may be hard to see right now, but I do believe in the democratizing power of mass social technology.

Look, you’re right, there is a lot to be concerned about; the speed at which we’re crossing new technological frontiers is far outstripping the ethical, moral, economic and environmental consideration that needs to be taking place at the same time. That failure will hurt us, and I’m glad that the tech-skeptics out there are raising these concerns. That said, just consider the ways you’ve used technology to spend a day in quarantine and then imagine trying to make it through a day under lockdown just 15 years ago when none of these technologies existed.

The sad fact is that, as a city with 25 percent of its population living in poverty, we are going to be very hard hit when this is all said and done. The people most likely to suffer from this illness are poor people and people of color; people, who work low-paying frontline jobs with little to nothing in the way of health insurance.

Telemedicine, work from home, food delivery apps, online stock trading, Zoom meetings, FaceTime, literal years worth of streaming video content. The truth is we’ve never been better prepared to maintain social interaction under a regime of social distance, and it’s all thanks to this technological tsunami that’s been raging over us for the past few years.

This pandemic has the potential to bring all of humanity together in the way that only something like an alien invasion could do, and I’m convinced that this potential will ultimately break down partisan divides and prove to be an antidote to the demagogues taking up so much oxygen right now.

LP: Which brings us to our political leadership right now. Forty years ago, Ronald Reagan said that government wasn’t the solution, it was the problem. I’m hopeful that one of the ramifications of all this will be that maybe competent government comes back into vogue.

AR: This pandemic caught our leaders off guard and the president and his administration are, to put it mildly, playing catchup. We may have to accept the sad truth that the American government may not lead the world out of this crisis.

Our political response has largely been incoherent, insufficient and incompetent. The concept of “American exceptionalism” is being put to test on the global stage and the world perception of us may not match what we may accept as an unassailable truth.

But even if Washington isn’t going to be at the vanguard of this battle, it doesn’t mean there isn’t strong American leadership. Our research scientists, biotech firms and healthcare workers are the best in the world and they are leading.

You mention competent political leadership. I caught an interview between Fareed Zakaria and Lee Hsien Loong, the prime minister of Singapore. Zakaria attempted to congratulate Lee on his administration’s effective efforts to curtail the spread of coronavirus, but Lee demurred, saying it was far too early to declare victory over the illness.

This pandemic has the potential to bring all of humanity together in the way that only something like an alien invasion could do, and I’m convinced that this potential will ultimately break down partisan divides and prove to be an antidote to the demagogues taking up so much oxygen right now.

Instead, Lee emphasized that his administration had tried to be as transparent and honest as possible, resisting the urge to sugarcoat bad news while providing useful information to citizens. He also acknowledged the importance of expecting cooperation and enforcing compliance with social restrictions, but to provide assistance to make cooperation and compliance more palatable to the population.

![]() In terms of confronting the spread of the virus head-on, Lee described mobilizing the government to develop and distribute test kits immediately, and to implement not only direct testing but contact testing using cellphone metadata. All of these are steps the U.S. could’ve taken but didn’t. And our soaring rates of infection are damning proof of our failure to act.

In terms of confronting the spread of the virus head-on, Lee described mobilizing the government to develop and distribute test kits immediately, and to implement not only direct testing but contact testing using cellphone metadata. All of these are steps the U.S. could’ve taken but didn’t. And our soaring rates of infection are damning proof of our failure to act.

LP: We just did a Citizen Town Hall with Ali Velshi, in which he talked about this as one of journalism’s finest hours. He defined the role of journalism as “bearing witness” and “speaking to truth to power,” and it made me feel optimistic, despite everything we’ve been going through. What’s made you feel optimistic of late?

AR: What’s making me feel optimistic is learning about how we develop vaccines today, as compared to a few years ago. It’s true that we’re still looking at least a year until mass distribution of a coronavirus vaccine, but that’s still pretty remarkable. There are currently over 40 teams around the world working on Covid-19 vaccines. Fast and powerful computers can sequence the genetic code extremely fast and cheaply, which enables scientists to create those critical genetic fragments.

In other words, as soon as we identify a germ’s gene sequence, we can develop a vaccine for it. Our region is an epicenter of vaccine research and development. Penn Medicine, Johnson & Johnson, Merck, the Wistar Institute at Penn, just to name a few, have been trailblazers in finding cures for infectious diseases.

These research institutions will be called upon to help lead us out of the pandemic, and we must raise the funds for them to do so. This could help offset the financial damage the virus is doing to our region. It’s our responsibility to demand that both the medical and economic cures be accessible to all.

The other thing is, I’m continually moved by what ordinary Philadelphians are doing every day during this crisis to care for and support their neighbors and the small institutions that define our communities. It’s astounding how so many folks are going out of their way, taking the initiative to offer support. Whether setting up GoFundMe campaigns, virtual “tip jars,” or even sharing lists of local eateries offering take-out service, people are intuitively realizing that communities need to be tended to by those who live within them.

This is important, because the sad fact is that, as a city with 25 percent of its population living in poverty, we are going to be very hard hit when this is all said and done. The people most likely to suffer from this illness are poor people and people of color; people, who work low-paying frontline jobs with little to nothing in the way of health insurance. And this is on top of Philadelphia being the biggest city in America without a public hospital.

LP: So this is a running debate. Once we come out of this—and we’re likely not fully out of this until there’s a vaccine—is it possible to just go “back to normal.” Or is there a new normal—and what does that look like?

AR: My crystal ball is murky, but one thing is for certain: We are living through a global scale cataclysm. The world will not return to a recognizable “normal” after this, but that doesn’t have to be cause for despair. What makes the coronavirus epidemic particularly dangerous, and potentially catastrophic, is that it is simultaneously a health crisis and an economic crisis; after this we can no longer pretend that public health and the national economy exist in separate spheres, nor can we pretend that the economy was on any kind of secure and sustainable footing in the decade plus since the 2008 economic collapse.

In many ways the crisis we’re experiencing right now is a reflection of the fact that we did so little to make the kinds of corrections, changes and redirections to our economic system that we should have ten years ago. This attempt to return to business as usual, to bail out the banks and neglect workers, healthcare, education and housing has come back to haunt us. We have another chance and the benefit of recent hindsight to chart a course out of this crisis that doesn’t hit the same potholes of our prior “recovery.”

Trying to understand what in this world is permanent, dependable and sturdy enough to build a foundation upon requires that we reconnect with ourselves and the people closest to us in ways that we couldn’t have conceived of under any other circumstances.

Another sure shot prediction is that the march of technology and its insinuation into every facet of our lives will continue. More and more, computers that currently sit on our desks and our laps will become computers that we wear. And computers that we currently wear will become computers that are implanted into our bodies and brains (whether that implantation involves our knowledge and consent is an open question).

But gadgets aside, the big story of the future is data. Billions of digital eyes and ears will be recording, sorting, compiling and aggregating a virtually limitless ![]() quantity of data about each of us and everything around us. The synthesis of that megadata will illuminate more about the workings of life itself than we can possibly comprehend at present. This future presents an opportunity to learn, to share knowledge and to make the world far better than it is today—or far worse. It all depends on who controls that trove of data, and to what end it is used. That’s the one thing we can’t predict.

quantity of data about each of us and everything around us. The synthesis of that megadata will illuminate more about the workings of life itself than we can possibly comprehend at present. This future presents an opportunity to learn, to share knowledge and to make the world far better than it is today—or far worse. It all depends on who controls that trove of data, and to what end it is used. That’s the one thing we can’t predict.

LP: This is heady stuff. It’s nice to get beyond the day-to-day data—how many are infected, how many have died—and think about what all this might mean. Now get back to The Sopranos. You’re much more highfalutin than me. I’ve been watching The Real Housewives of Atlanta.

AR: Now that has an impressive narrative arc.

Photo courtesy Edan Cohen / Unsplash