To this story in CitizenCastLISTEN

That’s what I argued, as recently as Sunday morning on Channel 6’s Inside Story. “Way to go, asshole,” one friend texted me in the wee hours of election night, when Trump seemed to be running the battleground state table. I refrained from taking the bait and responding defensively; to do so would have been a narcissistic act of Trumpian proportions.

I spent Wednesday simultaneously yearning for sleep and dialing up the smartest observers of politics and civics that I know, trying to glean how, yet again, those of us in a certain bubble had so badly missed the mood of the electorate.

But I did feel duped by all those polls, which gets us to the first loser of election night: the pollsters. How was it that the smart set had yet again gotten its forecasting so wrong? I spent Wednesday simultaneously yearning for sleep and dialing up the smartest observers of politics and civics that I know, trying to glean how, yet again, those of us in a certain bubble had so badly missed the mood of the electorate. Ajay Raju, the law firm honcho, philanthropist and Citizen chairman, had one of the smartest takes, arguing that many of us exist in a confirmation bias feedback loop.

“The talking heads, the pollsters, and the pundits are all reporting from the same old playbook,” Raju told me. “They conduct autopsies rather than biopsies.”

Raju went on to tick off the night’s winners and losers. The Democratic Socialists? Losers, not only because their much-hyped blue wave never materialized, but also because Cuban refugees bought Trump’s cartooning of Biden as a socialist and delivered him the state.

The absence of a progressive wave in an election with tremendous turnout will have longstanding consequences. Big Tech can now breathe a sigh of relief, as efforts to break up monopolies like Facebook will likely lose steam in the new political reality.

If Biden prevails, as seems likely, and the Senate remains in Mitch McConnell’s oddly purple hands, as also seems likely, and the House has less of a majority than before, ideas that were the predominant province of the left—the Green New Deal, court-packing, Medicare for All—will now not see the light of day. What does this say, other than that the country seems to yearn for moderation and incrementalism?

“Think about this,” Raju cautioned me. “If it weren’t for Covid-19, and Trump’s bungled handling of it, this would have been a Trump landslide.”

Talk about your inconvenient truths. It’s hard for progressives to fathom that, isn’t it? It’s far easier to write off those Trump voters as nothing but racists and “deplorables”—remember that lovely description from four years ago?—than to react to the latest election results with a measure of humility and introspection. Something in the Democratic message or style has, twice now, failed to convince damn near half the country that they’ll be better off in the hands of someone who doesn’t compulsively lie, tweet nonsense, and kowtow to white supremacists and Putin.

The morning after election night, U.S. Senator-elect John Hickenlooper—the pride of Narberth—was on TV, exhibiting the type of open-minded governance these divided times call for. He was explaining that he favors an ambitious, costly congressional Covid-19 relief package, but he resisted the urge to demonize those who might disagree.

Attend our Ideas We Should Steal FestivalDo Something

And therein lies the opportunity in this weird political moment. If we have more professional practitioners of practical politics, like Hickenlooper, and less shouting, name-calling and ideologically-driven speechifying, maybe divided government will be a blessing.

Think of it: Had the Blue Wave occurred, yes, it would have been a moving repudiation of Trumpism. But we know what would have happened after that, because we’ve seen it time and again. A Democratically-controlled presidency and congress would have overreached, leading to a wave in return two years from now, as happened in 2010, when a historic Republican congressional takeover followed President Obama and Speaker Nancy Pelosi’s passage of the Affordable Care Act without a single Republican vote.

“The talking heads, the pollsters, and the pundits are all reporting from the same old playbook,” Raju told me. “They conduct autopsies rather than biopsies.”

Politics is actually a discrete skill. It’s the hard work of building coalitions, of working relationships, of matching up strange bedfellows in common cause, of balancing compromise with adherence to bedrock principle. It’s not pretty, because you never get all of what you want. We’ve seen what happens when those who haven’t practiced the art of politics give it a go—you need look no further than the various incompetencies of Trump and, closer to home, our former Attorney General, Kathleen Kane.

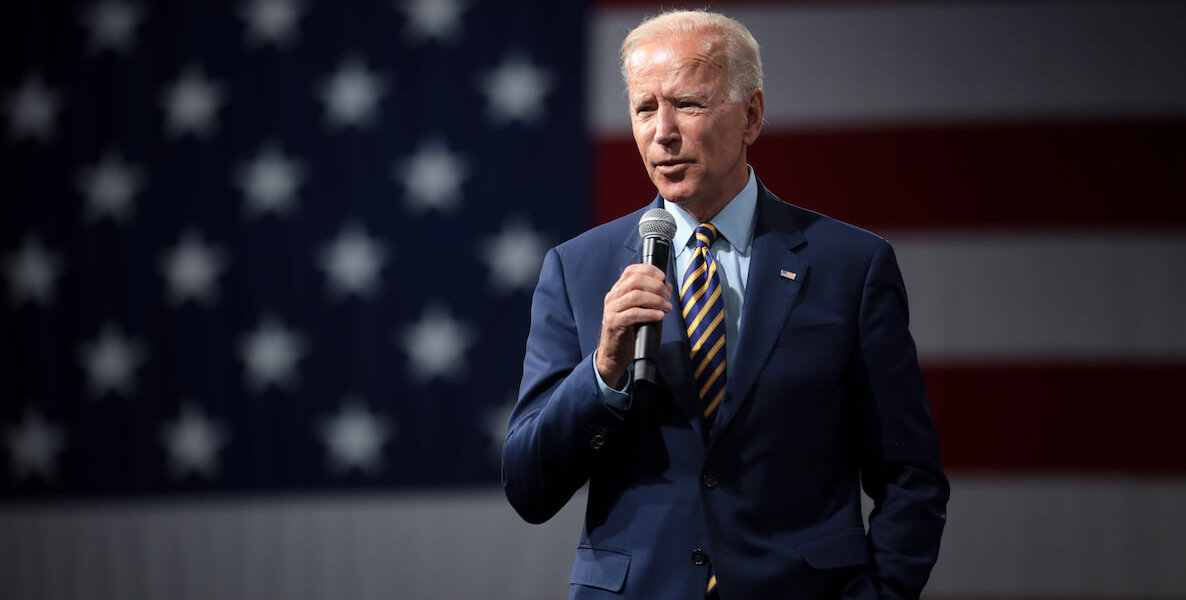

Joe Biden has spent his entire life doing politics, and he has romanticized the bipartisan days of his Senate heyday, when he worked with, and praised, southern segregationists in order to secure their votes on progressive pieces of legislation. You can be morally-outraged at that, or you can acknowledge that it’s a big country out there, and not everyone is going to agree with you, and politics is about finding a way to get them on your side anyway.

Politics of this sort has fallen out of favor, but there are ample examples of how it can make real people’s lives better. In this very state nearly two decades ago, then-Governor Ed Rendell passed a historic budget funding education at record levels, and he got the votes for it by promising Republicans that not only wouldn’t he campaign against them when they were up for reelection, he’d write them a letter of praise that they could use in their advertising. The zero-sum politicos were outraged, but Rendell knew how to cut deals to benefit his constituents. And if they were happy, the insiders and apparatchiks would eventually come around.

More recently, in New York, Governor Andrew Cuomo’s ju jitsu-like backroom moves—as recounted in Michael Shnayerson’s 2015 biography, The Contender—has delivered more progressive accomplishments than any other state’s chief executive in recent history, yet he remains unpopular with progressives, who’d rather be right and lose than compromise.

You’d think that an elected official who banned fracking, who was ahead of the curve on a $15 minimum wage and marriage equality, and who passed free college tuition would be a liberal’s dream, but Shnayerson shows how Cuomo, skeptical of corrupt downstate Democrats, secretly empowered a renegade group of the General Assembly called the Independent Democratic Caucus to collude with Republicans to get him what he wanted. (Which may explain why Cuomo fought New York Mayor Bill DeBlasio so long on a millionaire’s tax—he owed much of his progressive agenda to a coalition that included Republicans.) Shnayerson shows the sausage being made and it is a thing to behold—the deals, the head-fakes, the way Cuomo settles scores and runs them up at the same time.

Given that as context, how ironic it is that a near octogenarian lifetime pol, working with a Senate controlled by the opposite party, just might be precisely the change agent America needs. We know we won’t get sweeping, unilateral, New Deal-like legislation from Biden now, but we may get something that’s more healing. We may get a modicum of bipartisanship, particularly when it comes to infrastructure—there’s long been a widespread coalition at the ready to do something bold about the state of our roads, bridges, highways and electrical grid.

Larry Platt on politicsRead More

Could a President Biden empower the Problem Solvers Caucus in much the same way Cuomo used the Independent Democratic Caucus to move the needle in New York? That would require a deft political touch, and it would also be a way to set a new, more constructive tone for our politics.

Politics is actually a discrete skill. It’s the hard work of building coalitions, of working relationships, of matching up strange bedfellows in common cause, of balancing compromise with adherence to bedrock principle.

For a brief period in the ‘90s, before all of Bill Clinton’s personal shenanigans, it seemed like just such a tone had been struck. As a young ambitious Governor in Arkansas, Clinton would attend events toting books by this obscure George Washington University sociologist Amitai Etzioni, who, along with a handful of other scholars, kicked off the Communitarian movement of the ‘80s and ‘90s.

Communitarianism held that, beginning in the late ‘60s and early ‘70s, our politics became obsessed with rights—the granting, demanding and denial of them—to the exclusion of talking about responsibilities, particularly in terms of our obligations to each other and our communities. When Clinton announced his longshot campaign for president in 1991, he promised leadership “that will provide more opportunity, insist on more responsibility, and create a greater sense of community for this great country.”

Throughout his presidency, Clinton governed as a Communitarian, rejecting both the right’s “fend for yourself” ethos and the left’s habit of rewarding loyal voting blocks with new entitlements. Instead, programs like AmeriCorps and Welfare Reform—which rewarded work—reinforced long-frayed civic bonds.

More than anything, the language of Communitarianism keeps the pursuit of the common good front and center in our politics. Of course, Etzioni’s emphasis on the importance of common things wasn’t new. It’s what Lincoln was getting at when he appealed to the “better angels of our nature.”

Amitai Etzioni on CommunitarianismDelve Deeper

That was classic Communitarianism—the sense that to pursue the common good is really to benefit us all. It’s a politics where self-interest and empathy converge. The Greatest Generation knew this. On his deathbed six years ago, my 87-year-old Dad, a World War II veteran who joked that, stationed in Seattle, he protected the Pacific Northwest from Japanese attack, wondered just when paying your taxes became so damned political. “It was something you did because you were part of a community,” he said, “and you had an obligation to the next guy.”

An obligation to the next guy. What a novel concept that would be now, huh? Joe Biden might just be uniquely situated to strike a Communitarian pose; how else to restore the soul of America, after all, than to remind us—in prose and policy—that we’re all in this together?