On the final night of her campaign, Hillary Clinton stood in front of Independence Hall harkening back to the country’s founding, and hoping to generate voters’ excitement within contemporary Philadelphia. Yet despite the city’s 1.55 million residents, and more than 1 million registered voters, only 728,577 people cast ballots (of which 709,618 voted for president). While Bucks and Montgomery counties combined have just 1.44 million residents, they managed to eke out 349,791 and 446,969 votes respectively, for a total of 68,203 more votes than Philly. Given suburban rates of voting, Hillary probably should have made her last appeal for support in front of a Wawa instead.

Philadelphians, like residents of all major American cities, typically vote at rates 5 to 15 percent lower than their suburban and rural counterparts. Because of that lower level of engagement, and because they have for decades elected Democrats for local office, American cities are taken for granted by the Democratic party and often ignored by Republicans.

This creates a conundrum: American cities host two-thirds of the country’s population and generate 85 percent of its GDP, and yet their concerns, such as public transportation, affordable housing and poverty, aren’t part of political rhetoric or national election discussions. Worse, urban legislators are often pariahs at the state and federal levels of government. In nearly every state, there are perennial battles over decimating cities’ public school funds and arguments over the choice to fund highways instead of public transportation. And urban congressmen, state reps and mayors have little sway over these matters because state leadership, born of and supported by suburban and rural constituents, is unsympathetic to their issues.

Lack of voter turnout is a problem in nearly every city, not just every four years, but every year with local elections. According to an analysis from Portland State University, the top 30 cities average a turnout of 20 percent of the voting-aged population for local elections.

To compensate, cities have developed a robust urban innovation industry composed of civic leaders, nonprofits, philanthropies, and media (full disclosure: I was previously the editor and director of NextCity.org) who exchange ideas to improve cities. Instead of looking for help from Washington, there is increasingly an attitude among this crowd of shunning the dysfunction of Beltway politics in favor of incremental change at the local level. And in many ways, this works. One need only to look at projects like the Rebuild effort by the Kenney administration, which will make use of $300 million in bonds and $100 million in grants to restore and improve parks and libraries, to see that cities can leverage their own money to create big, local impact.

Yet, while more Americans who live in cities support the urban ethics of tolerance, education, opportunity, density and sustainability, those values will never become the national norm unless cities have greater representation in state and national government. And while the federal government may no longer be sending money to cities, it is still creating policies that impact metro regions. There’s no doubt that a significant change in Washington’s policies on immigration, trade agreements, abortion, gun control or healthcare will make waves in Philly and cities like it.

Following the election, there was much soul-searching by coastal media about how to fix the economic and social divides that had created the anger fueling Donald Trump’s rise. Reflecting upon the economic hardships that underpinned voters’ frustration, many pundits ranging from The New York Times columnist David Leonhardt to Vox.com’s Matt Yglesias proposed solutions to economic inequality and rural stagnation. But while these problems are worthy of new solutions, they register about an 8.5 on a scale of 10 in terms of difficulty (solving climate change being about a 10 out of 10).

There is a relatively easier way to solve the problem that is distorting American political culture: Ensuring urban residents vote at the levels of their suburban and rural counterparts. Getting out the vote is not a sexy topic, but it will become increasingly important as the political landscape continues to shift. Cities represent an untapped opportunity for both parties. With the demise of organized labor, Republicans have a shot at landing more and more state rep, house and even mayoral positions. Meanwhile, while southern states like Texas are growing, a surge in urban voters could turn those states into targets for Democrats.

Larger numbers of urban voters would have dramatic effects on state level representation, such as senator and governor positions, which in turn would affect national policies as well as who gets elected as president. And unless and until we have that urban-minded state-level representation, urban concerns and ethics will never get the national attention and funding they deserve.

Lack of voter turnout is a problem in nearly every city, not just every four years, but every year with local elections. According to an analysis from Portland State University, the top 30 cities average a turnout of 20 percent of the voting-aged population for local elections. Ironically, cities have an array of get-out-the-vote measures in place. In Philly, we have ward leaders, committee people, not to mention the efforts of politicians seeking election.

So why are they so ineffective? To begin with, many city governments have little turnover and are solidly Democratic, so there’s no urgency or incentive to increase voter registration and turnout. For Council members with lifelong jobs, it’s actually against their best interest to bring new voters into the fold.

Likewise, residents in cities that are run by essentially one party tend toward inertia, since the stakes in local elections seem relatively low. Voters figure, if it’s not one Democrat, it’s another, and that will be fine. Voting is habit forming, and so if voters don’t vote in local elections they aren’t as likely to vote in elections with state and national positions up for grabs.

Finally, cities tend to be full of the young and poor, demographics that correlate with the lowest rates of voter turnout. While Philadelphia has thousands of students, their high level of turnover makes their voter registration process difficult. And poor neighborhoods do not have the influx of people with clipboards seen in Rittenhouse Square or the sidewalks near Whole Foods every political season.

Beyond these factors are a slew of logistical reasons why cities can be tough for getting out the vote. It’s harder to access voters who live in apartment buildings than single-family houses. Some neighborhoods, say North Philly or Mantua, are seen as off-limits to door-knocking volunteers given their higher crime rates. Cities have large numbers of immigrants, and those without citizenship are essentially time-wasters for GOTV efforts, so some immigrant-heavy neighborhoods may be skipped.

If the 40 CDCs in Philly developed a core GOTV curriculum, and then studied turnout rates for each election, and discussed what methods were most effective, Philly could rapidly prototype voter registration and turnout at the neighborhood level. And Philly’s example could spread to several other cities like it.

But unlike figuring out how to bring back manufacturing to the Rust Belt or how to revise the tax code for greater equity, these are relatively easy problems to solve, especially in this age of urban innovation. While getting out the vote has long been a priority for partisan organizations or national GOTV organizations, it hasn’t been a focus of the urban innovation industry. And that may be why it’s been so ineffective thus far. Much research shows that voting has more to do with social connections than political views. Perhaps if voter registration and turnout were truly a non-partisan, social, neighborhood-level exercise, it would be more effective.

In Philly, there is already one group of entities poised to take this on: Community Development Corporations, those local nonprofits that help neighborhoods with everything from Fall street cleaning to building affordable housing. In Philadelphia, there are more than 40 members of the Philadelphia Association of CDCs, an organization “dedicated to advocacy, policy development and technical assistance for community development corporations and other organizations in their efforts to rebuild communities and revitalize neighborhoods.” Traditionally, there has been little funding for GOTV among CDCs, and because other entities already occupy this space, they have not focused on this issue.

Yet CDCs are primed to take the urban innovation approach to GOTV and make a big difference. Building upon the voter outreach that CDCs already do, they should develop new methods of coordinating their efforts, developing a core-curriculum of voting-related activities and regularly and methodically sharing best practices within each city and among cities nationwide. Do absentee voter forms or transit assistance do more to increase turnout? Do local information sessions or political panels help more to get people engaged? There’s no one collecting the answers specifically for the urban context, and it’s costing cities untold amounts of funding and sympathetic government representation each election.

If those 40 CDCs in Philly developed a core GOTV curriculum, and then studied turnout rates for each election, and discussed what methods were most effective, Philly could rapidly prototype voter registration and turnout at the neighborhood level. And Philly’s example could spread to several other cities like it. While each city has a diversity of neighborhoods within it, there are recognizable neighborhood typologies among all American cities whose voting patterns are likely to be similar.

While in some cities, there is still a need to register more voters, in Philly, we should focus merely on turnout for two reasons. First, research shows that merely voting once increases the probability of voting again; by comparison, registration is an ongoing battle with no guarantees of turnout. Second, Philly actually has pretty robust registration—with 1.1 million voters already registered, and with almost 200,000 non-citizens in the city, this means most people can already cast a ballot. Yet, there were almost 400,000 people who were already registered for the last election who didn’t show up on election day. Finding out why, and finding out how to ensure those people vote next year, is a problem we can solve.

In the past two decades, networks of politicians such as the Conference of Mayors and National League of Cities, foundations such as Bloomberg Philanthropies and Ford Foundation, and nonprofits from the big ones like Brookings to small ones like Philadelphia’s Center City District have transformed cities into widely recognized leaders in entrepreneurship, sustainability and progressive policy. They have done this by spreading ideas like the High Line from New York to St. Louis, or CitiStat, a data-driven approach to city management, from Baltimore to Los Angeles. It’s time that cities, proud pioneers in so many other areas, harness this spirit of experimentation and collaboration to show they can lead in voter turnout, too. Our cities’ welfare depend on it.

Correction: An earlier posting of this story slightly misstated the number of votes cast in the 2016 general election. It was 728,577. It also misstated the difference in numbers between Philly and suburban voters; it was 68,203.

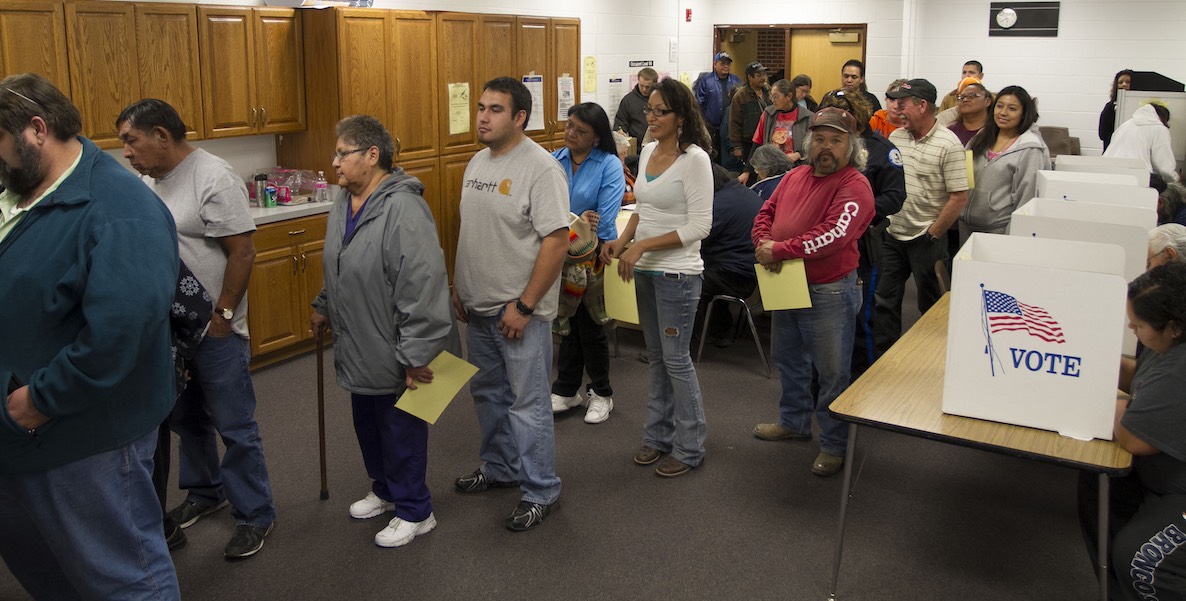

Photo by Josh Middleton