In the spring, a friend texted me a photo circulating on Twitter showing Veterans Stadium, Citizens Bank Park, the Spectrum, the Wells Fargo Center and Lincoln Financial Field all standing at once.

I replied, “I saw Bruce Springsteen in every one of those venues!” My friend, not a Springsteen fan, found it hard to believe somebody would see the Boss that many times.

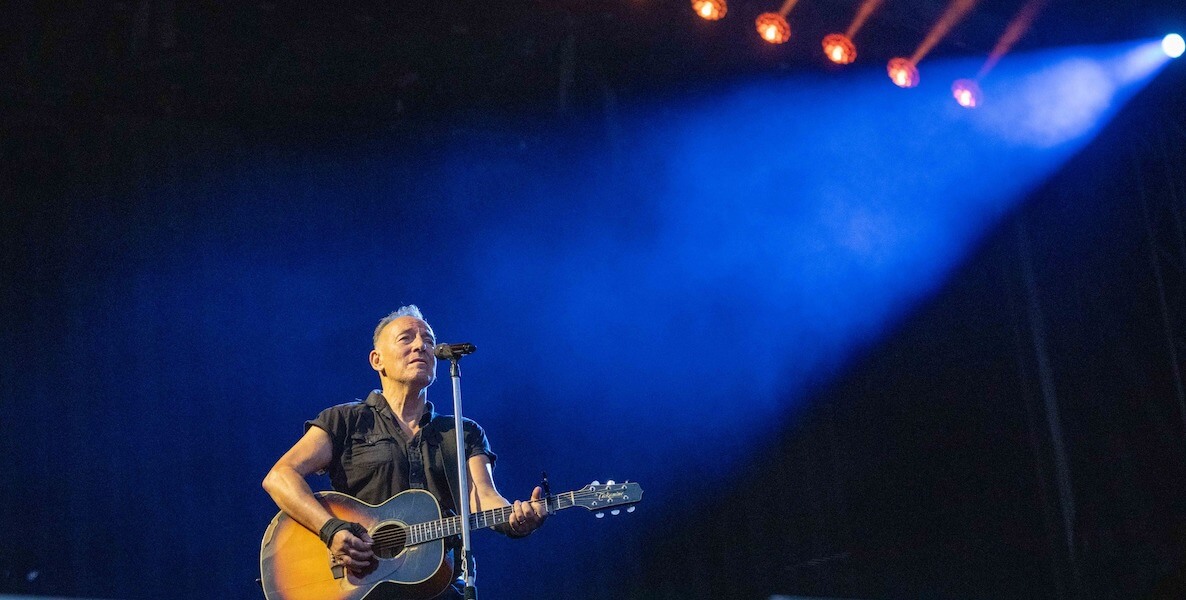

This week, Springsteen was to make his second trip of the year to South Philadelphia, bringing his tour to Citizens Bank Park. The shows were postponed at the last minute due to Springsteen having “taken ill,” according to a message posted to his social media accounts. The shows will be rescheduled; as my text to my friend proves, the Boss keeps coming back. I saw him in March at the Wells Fargo Center, and I’ll be there again at the Bank whenever they set the dates. They will be my tenth and eleventh Springsteen shows. (Paltry, compared to some, I know; my brother, whom I owe for my intro to Bruce, as well as entree to tickets for several shows, has seen him more than 50 times).

Through those stages of life, on all those stages in South Philly, I’ve come to hear his music as not just the early roar of a scrawny Jersey boy, but as a reflection on the darkness and light in a lifetime.

Why keep returning? The music keeps returning to me in new ways, a companion through the stages of my life. And through those stages of life, on all those stages in South Philly, I’ve come to hear his music as not just the early roar of a scrawny Jersey boy, but as a reflection on the darkness and light in a lifetime. Rock ’n’ roll started as romping rebellion, but it’s grown to reckon with what happens after the rebellion. Springsteen’s shows have become tent meetings for taking stock.

Growing up with Springsteen

I first saw Springsteen in the summer of 1985, at the Vet. I was almost 19, just finished a year of college, and in the company of high school friends, feeling flush with independence (they didn’t even card us at the bar we went to beforehand). Next was 1992 at the Spectrum. It was just before I flew to my best friend’s wedding, a first “turning point” event in my adulthood. That night I was filled with thoughts of love and commitment, and the optimism embodied in Bruce’s single, Better Days.

Then 1999 — a hallowed return to the Spectrum for the Boss, one day after he turned 50. I was with my wife and my first son. Sort of. He was in utero, but it counts, right? Springsteen opened with Growing Up, and I sure felt I was, in a new way. Bruce called out to his mother in the audience; my wife and I were starting a family, that next phase of The Ties That Bind, the song that opens The River, Springsteen’s first album of adult reckoning.

Springsteen’s songs, for all their bravado of being born to run to a mythical promised land, remind us that shadow always sits shotgun on the journey, and we must be ready not just for the unexpected wreck, but for reassembling the shattered pieces afterward.

The 21st century brought me to shows in 2003 and 2007, my only one at the Linc and my first at the Wells Fargo Center. I was now a father to two sons; the nation was warring on terror. Springsteen’s personal anthems were always small-p political, but he’d shied away from Politics. Now, his album Magic focused us on his sense of growing national tricks and hypocrisy, and in songs like American Land, he pointed out that “the hands that built the country we’re always trying to keep down.” Springsteen stumped for Obama; the son who was dancing in the dark of the womb at the Spectrum in ’99 came canvassing with me for him too.

Last decade included my first show with my sons out of the womb, at the Bank in 2012, and our whole family, for the first time, listening to the whole of The River at Wells Fargo in winter 2016. That album closes with the mournful Wreck on the Highway, where a man witnesses a crash, and seems haunted by its image, as if it’s coming for him. That fall it did come for us — a mix of the shattering death of a dear friend (my best friend’s wife, from that wedding in ’92 that heralded those better days), and the presidential election, a true wreck on our national highway. Springsteen’s songs, for all their bravado of being born to run to a mythical promised land, remind us that shadow always sits shotgun on the journey, and we must be ready not just for the unexpected wreck, but for reassembling the shattered pieces afterward.

Living and knowing you won’t live forever

It was in that duality — of wreckage and rebuilding, shadow and light, fear and hope — that I heard Springsteen this spring. After decades making meaning as a theater director and civically engaged artist, I’d entered a new arena of exploring meaning — as a hospital chaplain. The day of the concert, I’d been in the presence of an adolescent with the moxy of one of Bruce’s early Asbury Park creations and an elderly patient, about Springsteen’s age, but so different — speech slurred, writhing. Or was she different? Even through her illness, she roared on, raging against the dying of the light. Ready, as Springsteen would say, to prove her spirit all night.

Rock music, and Springsteen’s brand particularly, is about staring in the face of mortality even if you can’t possibly believe it’s going to come. But at Springsteen’s age, you are both living and knowing you won’t live forever. On a daily basis as a chaplain, I witness people, of many ages, holding those truths in each hand. I’ve heard them crack wise about it. I’ve heard them invoke their favorite music, including The Boss. And I’ve seen them and their families lonely and afraid.

They are face to face with Springsteen’s Darkness on the Edge of Town, a shadowy region “where no one asks any questions / Or looks too long in your face.” Except as a chaplain, that’s the job: To ask questions and be present with the scared in their shadows. It’s humbling. There aren’t answers. You don’t fix this particular wreck. You hold space and honor the life that’s happening, even as it’s fading.

As a chaplain, that’s the job; to ask questions and be present with the scared in their shadows. It’s humbling. There aren’t answers. You don’t fix this particular wreck. You hold space and honor the life that’s happening, even as it’s fading.

Springsteen seems to have always done this. At 30, in Stolen Car, he wrote “I ride by night and I travel in fear/That in this darkness, I will disappear.” Soon after, he wrote of a Vietnam vet pleading that no one “shut out the light” as he wards off his demons. At his concert in March, he paired Last Man Standing, a tribute to a comrade from his first band whose death left Springsteen the only surviving member, with the early epic Backstreets. The juxtaposition made Backstreets sound weathered — “Blame it on the lies that killed us/Blame it on the truth that ran us down” — as if at 25, Springsteen saw the end coming. He seems to have always known, as the playwright Tennessee Williams said, that “the tick of the clock is loss, loss, loss.”

And yet, as I see in hospital rooms regularly, and as Springsteen wrote in his darkest album, Nebraska, “at the end of every hard-earned day / People find some reason to believe.” They believe many things, to be sure. And not all find their reason, to be more sure. But the quest. The bravery to be present in your vulnerability. The chance to enter each stage of life, even the final one, with a question that drives you. That’s perhaps the way to live with the clock’s loss, and to wrestle meaning from each tick.

In a May story in The New Yorker, Springsteen said,

Every artist has a story to tell. Over and over and over and over and over and over again … If you’re doing it correctly, it morphs every time you tell it. More information is revealed. At the same time, you’re still rooted in where you came from.

Springsteen, our city has always felt, came from here, from each of those South Philly stages. He also comes from those stages of life that take us from flexing, almost-19-year-olds to those nearing their shadows. In a hospital room with a dying patient or high up at the Bank next to my son, I return to his stories, listening for what is revealed. Don’t shut out the light, Bruce. Not yet.

David Bradley has had a long career as a theater director, teacher, and civically engaged art-maker, and since 2022 has worked as a hospital chaplain.

![]() MORE MUSIC AND CULTURE FROM THE CITIZEN

MORE MUSIC AND CULTURE FROM THE CITIZEN