Shortly after Sasha Suda took the helm of the Philadelphia Museum of Art in 2022, she found herself facing one of many dilemmas uniquely suited to her ethos.

In a funding conversation with the Kenney administration, a City official commented on the paltry number of public school students taking field trips to the PMA — just 8,000 in 2021, compared to about 100,000 in 2005, and 150,000 at the nearby Franklin Institute. The reasons, Suda learned from her staff, were myriad — but solvable.

Security guards wouldn’t open the doors until 10am, when the PMA opens, which meant teachers, students and chaperones had to wait outside, no matter the weather. There was no room big enough for a whole class to eat lunch, or in which to do group programming, which made it hard for teachers and chaperones to mind the children. There was not a space where students could be loud, and run around, and have fun.

Suda set out to change that. Under her direction, the PMA turned a new, 3,000 square foot museum store into a gathering space for students, with tables and chairs from elsewhere in the building. She convinced guards to open the museum’s North Entrance doors for class groups when they arrive, and open the museum to students on days when it’s normally closed. She asked the PMA’s Board of Trustees to allow their meeting room — otherwise empty — to be used as a lunchroom (and then celebrated with them the subsequent scratches on their table). She started talking to architect Frank Gehry, who designed the PMA’s new ground floor expansion, about turning some of that space into a Learning and Education Center. (That’s in the works.)

Last school year, some 38,000 students visited the PMA, including 4,000 they bussed in to see its special exhibit of Black artists, The Time Is Always Now. Next school year, Suda is aiming for 50,000, with plans to expand its youngest audience every year.

This is all part of the 44-year-old Suda’s people-forward vision for the museum. These students might be future artists or art collectors, donors or curators or, most importantly, lifelong visitors to their city’s premier arts institution — but only if they feel like it is theirs to enjoy.

“We are here to build bridges, to connect people. We have this extraordinary opportunity to be a place to defy politics, if we do it well and with a lot of integrity.” — Sasha Suda, Philadelphia Museum of Art

That may seem obvious — businesses succeed by continuously growing their customer base, after all — but in the rarified museum world, community and accessibility have not always been a priority, even when leaders have acknowledged the need.

“On a macro level, within the industry, the business model has failed us,” Suda says. “One of the places it’s failed us in its investment in people: We’ve really been an object-oriented industry. Art is at the core of our mission, but if people don’t believe in what we do, this ceases to exist. We want to continuously find new stewards for the museum.”

These are “next gen” issues that museum leaders like Suda have to face in a way that serves two masters: those who want to see the museum remain a global and dependable bastion of high culture with globally significant exhibitions and major acquisitions, and those who want the museum to adapt to our time and place and community values.

Suda is doing both: This summer she announced the PMA’s 2026 partnership with PAFA to host A Nation of Artists, 120 American masterpieces from Phillies Managing Partner and Principal Owner John Middleton and his wife Leigh, whose collection is considered among the best in the world. That’s exactly the sort of tentpole exhibit that should bring visitors to Philly from around the world.

But Suda was also hired in 2022 with the explicit mandate to make changes that speak to our moment. To Suda, that presented an exciting opportunity: Create something new and better from what has long been a world-class institution — even if actually making change means facing discomfort and pushback from donors, board members and sometimes staff.

“Living in the present is an exciting thing as a leader,” she says. “We have a responsibility to honor the past, but also have it function as a guide to the future. I’m very, very comfortable with an outcome I can’t predict — that there are ideas and possibilities that live outside my imagination. That’s my superpower.”

“The best young talent in the museum world.”

An Ontario native, Suda first visited the PMA as an undergraduate student at Princeton University. “I have always loved and admired the Philadelphia Museum of Art,” she says. She got a PhD in medieval manuscripts from New York University, then spent eight years at New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art, before moving back to Canada where, in 2019, she became the youngest executive director of the National Gallery of Canada in Ottawa.

David Cohen (The Citizen’s board chair) was Ambassador to Canada when Suda was hired. He remembers meeting her in Ottawa, where he hosted a dinner with museum directors from around the world, who referred to Suda as “the best young talent in the art museum world.” That she chose to come to the PMA, Cohen says, is an “extraordinary accomplishment for Philadelphia.”

The search that led the PMA to Suda followed 13 years of leadership from Timothy Rub that ended with a rocky period: a sexual harassment scandal, layoffs, staff exits and what former Board Chair Leslie Anne Miller called a “cultural assessment” of the museum. That all culminated in the formation of the PMA’s first ever labor union — and its first staff strike, which coincided with Suda’s first day on the job.

“That was hard,” says Suda, who deliberately stayed clear of the union negotiations. “The rules of onboarding didn’t exist. I got to hear a lot from staff, both on the picket line and not. I saw a lot through the filter of social media, which can be harsh. There were 4,000 emails in a folder from people who wrote to me who were upset about the museum’s position.”

Since then, Suda says, she has worked to unify staff members around one common museum mission, a change from how the institution has often operated in the past. (PMA — and Citizen — Board Member Jennifer Rice, for example, recalls hearing about a curator for one department who refused to share a piece of art from their collection with another curator who wanted to borrow it for an exhibit.) Negotiations over salaries mean being clear about the PMA’s economics; inheriting staff who were disgruntled for years requires listening and being open to changing business as usual, from the curator level to guards to those who interact most closely with PMA visitors.

There have been growing pains, including staff and management changes that have ruffled feathers. But as Rice points out, Suda is in many ways the right person to navigate this moment. She is a high-brow academic, with a penchant for biking and motorcycles; she is statelier than her years, with a quirky fashion sense; she deeply admires the PMA’s critical heft, but wants it to be fun, as it is for her twin 10-year-olds whom she brings often to museum events. (Her husband, Albert Zuger, is an artist.)

“They’ll be running around, causing a ruckus,” says Rice. “I love that she’s not about making the museum precious.”

On a visit one day this summer, as Suda shows me around some of her favorite spots at the PMA, she greets by name and is greeted by staff members, trading jokes and asking after each others’ families. She easily moves from the public-facing patter of a museum director — showing off the new Gehry spaces and the planned Learning and Education Center — to a learned appreciation of the art itself, which is, after all, what truly makes up the PMA.

A couple of the pieces we stop at feel almost like stand-ins for the work Suda is doing at the museum. One is the first acquisition she oversaw, a work by Luisa Roldán, a “really important” 17th century Spanish sculptor. It is one small step towards increasing the museum’s artworks by women; it’s also the first Roldan the museum has ever owned. “We have this amazing collection that also has gaps,” Suda says. “We’re not going to fill them all, and we don’t buy art just because it’s by a particular person. But the Luisa Roldáns of the world are anomalous, and their stories are really intriguing so it made sense.”

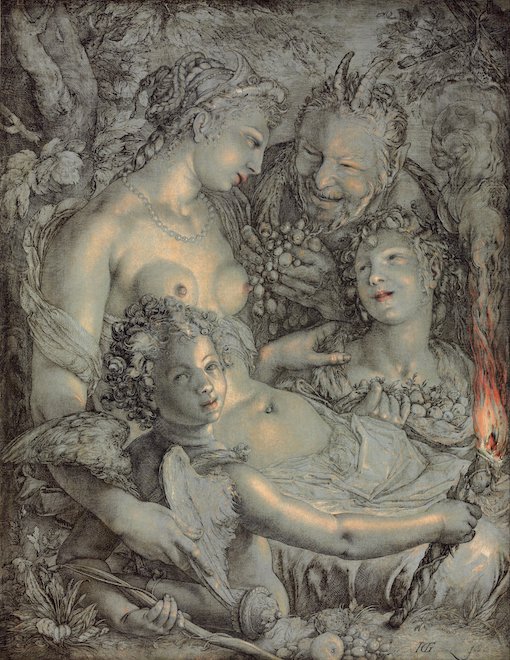

On a second floor gallery, we stop to look at a rare painting by early 17th century Dutch printmaker Hendrick Goltzius. Suda explains that it’s a goof, Goltzius thumbing his nose at the art establishment of the day that disdained printmakers. Depicting a Greek mythological scene, it’s a beautiful and absorbing work that includes meticulous hashmarks of the kind you’d see in a print. Suda loves the piece, and returns to it frequently.

“Sometimes I just come here, to sit and look at that,” Suda says. “It’s just a reminder that really anything is possible, with the right amount of patience.”

A museum for the people

Under former Director Rub, the PMA completed a two decades-in-the-making $233 million renovation, designed by Frank Gehry, that created about 20,000 square feet of gallery space in addition to new connecting walkways and other improvements. The original plan was for another several hundred million dollar capital project to create 80,000 square feet of new gallery space on the ground floor of the museum. For now that’s on hold.

“We’re one of hundreds of museums that have expanded their footprint in the last couple of decades,” Suda says, noting that the PMA is not among the few art institutions around the world that really struggle with space issues. “I’m part of a generation of museum directors whose job it is now to level set after decades of incredible growth within the sector, and to reconcile the institutional relationships with the people who make the institutions tick.”

That means, above all else, Philadelphians. “The PMA is on this hill,” says longtime board member Katherine Sachs, founder of ArtPhilly. “I feel like Sasha is walking off that hill, going in to the city, meeting lots of people. We are incredibly well-respected all over the world, but we live in Philadelphia and have a responsibility to our city and our citizens, and that matters to Sasha.”

Shortly after starting, Suda announced the museum would launch the Brind Center for African and African Diaspora Art, a donation of works and an endowment from museum trustee Ira Brind. About a year later, she announced the first curator of the Brind Center, which is the first time a PMA staffer and curatorial area will focus on African art. The Center will be housed in one of the new corridors Gehry designed.

“Sasha regularly puts the PMA in the global conversation. But she’s also not afraid to bring change; she’s not afraid to break things that need to be broken.” — PMA and Citizen Board Member Jennifer Rice

Over the last few years, the museum has introduced cultural heritage months with local artists, performances and special celebrations with community groups, as a way to broaden the population of people who spend time at the PMA. Museum Chief of Staff Maggie Fairs says these events have brought in record attendance, which has also translated into a flood of visitors for Friday Night Lounge and Pay-What-You-Wish Sundays.

“A key focus of Sasha is building a community that loves the museum, makes it irreplaceable in the city and all the communities that make up the city,” says museum Board of Trustees Chair Ellen Caplan. “It’s important for the board that everyone feels like the doors are always open.”

Last winter’s The Time Is Always Now: Artists Reframe the Black Figure (a name derived from a James Baldwin essay) was a survey of 60 paintings, drawings and sculptures from 28 contemporary African American artists, including Kerry James Marshall and Amy Sherald. For the U.S. premier of the show, which originated in the U.K., the PMA added several Philadelphia artists, including Roberto Lugo. A donor paid for the busses that brought public school kids — 50 percent of whom are Black — to the show, which had nearly 70,000 visitors in total.

The current exhibit, Boom: Art and Design in the 1940s, a survey of mid-20th century design that includes clothes, posters, furniture, paintings and sculptures, reflects a new vision for how the PMA is thinking about its holdings. Suda has set a goal that 30 percent of all special exhibitions is pulled from the PMA’s extensive collection of works. Boom is entirely pieces the PMA owns, including 40 percent that have never been on display before.

“Sasha reminds us what an amazing institution we have,” says Rice. “Because it’s in our backyard we tend to take it for granted. She regularly puts the PMA in the global conversation. But she’s also not afraid to bring change; she’s not afraid to break things that need to be broken.”

Growing pains

As expected (especially in Philadelphia) that verve for change does not sit well with everyone. Several people told me that some longtime board members are displeased with Suda for focusing — too much, they say — on inclusion, for what they consider a narrow focus when it comes to exhibitions, and for a slow start to fundraising.

Internally, staff turnover — even when necessary — has caused some chaos and employee dissatisfaction, and the union over the last few years has complained that Suda’s management team has not honored all of the aspects of the collective bargaining agreement negotiated under her predecessor. Some of that can be chalked up to the natural disruption of a new chief executive, who has brought in her own team and instituted changes.

Local 397 President Halcyone Schiller, a museum conservator, says she is cautiously optimistic following the signing of a new collective bargaining agreement in early August. “We’ve been met with more consideration than I previously experienced from management in terms of problems and how to solve them,” Schiller says. “We are closer to a place of labor peace than we have been the whole time we’ve had this union.”

“I’m very, very comfortable with an outcome I can’t predict — that there are ideas and possibilities that live outside my imagination. That’s my superpower.” — Sasha Suda

The major sticking points for the union, Schiller says, are what you’d expect: economic issues, like low salaries that make maintaining cultural careers difficult. Those are among the concerns that Suda’s generation of museum leaders have to address in a way their predecessors didn’t. They also must face the consequences of significant federal funding cuts since President Trump took office again in January. (The PMA lost one $250,000 grant.)

For the last several years, American museums have also faced uncomfortable questions about what and who they are for. How can they stand behind a collection that is primarily made up of the works of White men? Should they hoard sometimes tens of thousands of pieces of art — in the PMA’s case 90 percent of a 270,000-piece collection — that never go on display? Should they return art to countries from which they may have been “stolen?” Which artists get a place in the canon — and who gets to decide?

After the scandals during Rub’s tenure, and the racial reckoning of 2020, in 2022, Suda released an Equity Agenda with specific goals: 40 percent of employees from diverse backgrounds by 2025; 35 percent supplier diversity by 2025; $5 million raised for African American art by 2025. PMA spokesperson Maggie Fairs says the museum has met those goals, and that thinking about diversity and inclusion is now embedded across all of the museum’s endeavors.

“An extremely exciting moment to be in”

As she approaches her third anniversary at the PMA, Suda this summer announced the partnership with the Middletons, a major coup for the museum. The show is expected to bring tens of thousands of visitors to the PMA and PAFA next year, as part of the 2026 semiquincentennial celebration.

Some of Suda’s ideas for modernizing the PMA involve smaller changes: She envisions teen drop-ins every night until 9pm, and benches with charger stations “so people can spend 15 minutes in the gallery looking at things, but also can spend 45 minutes working on their phones and don’t think they have to leave” — like how she used to enjoy the Met, using her staff pass to wander its galleries on her off days and just get comfortable.

Others are huge, and require a commitment from her and from the board that she will be here for the long haul. Standing on the balcony of the museum’s Great Stair Hall, surrounded by the Constantine tapestries that have hung on the walls for decades, Suda says she hopes to be there long enough to rehang the museum, pulling from the PMA’s collection and presenting works that resonate with people now, and in the future. It’s a curator’s dream, but also a promise: Suda has no intention of going anywhere.

“People want to come to a museum and experience things they’ve never seen before and stretch their minds and their curiosities,” Suda says. “We are here to build bridges, to connect people. We have this extraordinary opportunity to be a place to defy politics, if we do it well and with a lot of integrity. I find that to be an extremely exciting moment to be in.”

![]() MORE ART, ARTISTS, AND CULTURE FROM THE CITIZEN

MORE ART, ARTISTS, AND CULTURE FROM THE CITIZEN