Growing up in West Philly, Carlo Campbell remembers being afraid of the Philadelphia Roundhouse.

For almost six decades, the massive concrete headquarters of the Philadelphia Police Department loomed over 7th and Race streets as a physical manifestation of police brutality in Philly. As a Black man living in the city, Campbell was warned about racist policing tactics his friends had experienced in the 70s and 80s — the legacy of which continue today.

Everything Campbell heard about the building was so awful, he began to avoid stories about it. He even started steering clear of TV shows like The Wire and Law and Order, which depicted policing. He made it a personal goal to never step inside. Now, while he appreciates the Roundhouse architecture — his wife is passionate about historic preservation — he thinks it might be best for it to be torn down so that Philly can put the building’s violent past behind it.

“It’s, like, at a certain point, they said, Hey, we have to tear down Jeffrey Dahmer’s apartment complex. He was one dude. It was one dude’s acts,” Campbell says. “So what about a legion of dudes over decades and decades?”

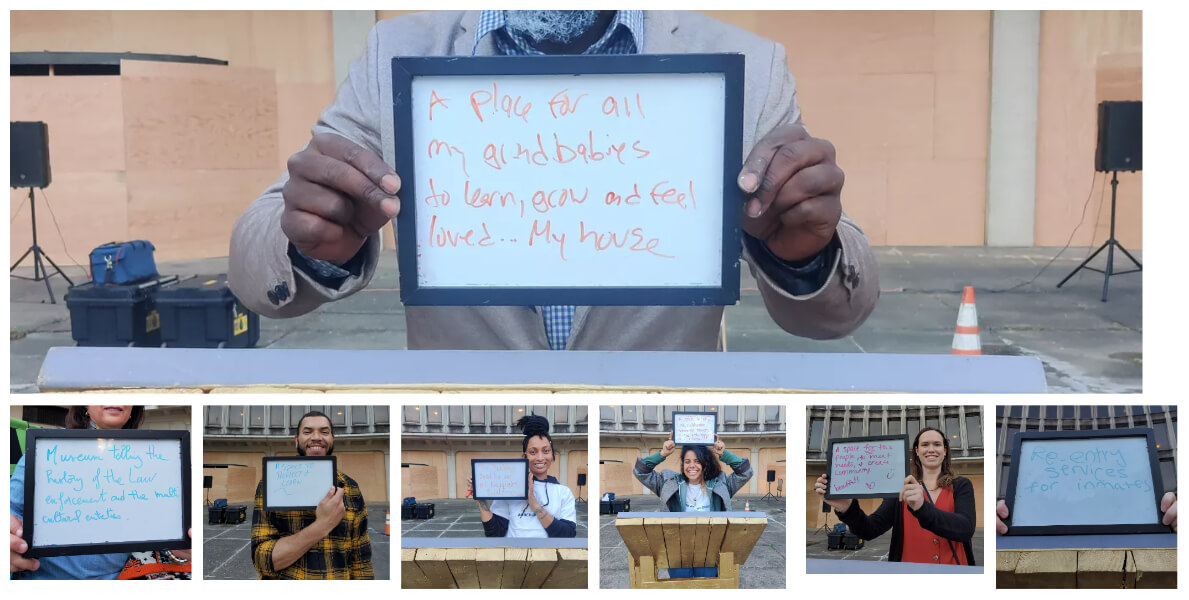

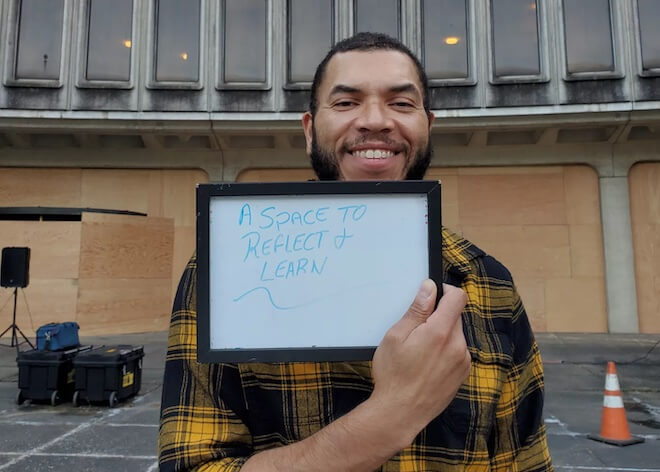

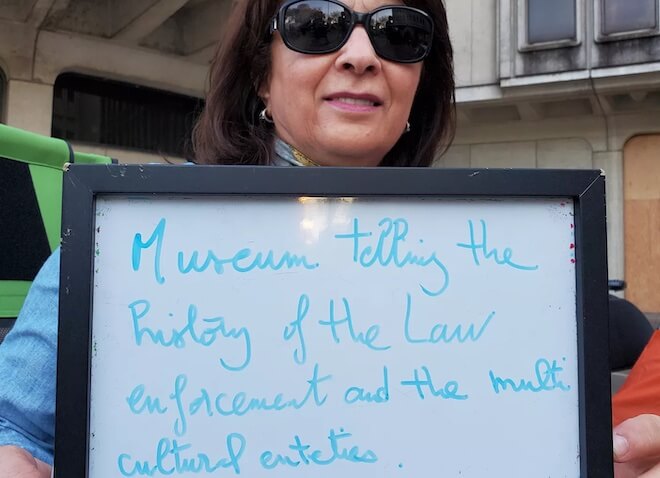

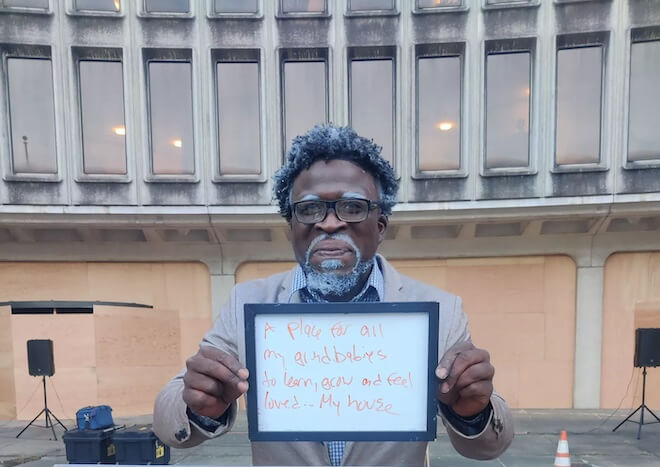

Campbell is one of dozens of Philadelphians who gathered on the front steps of the Roundhouse on October 15 to share his views on what the City should do with the building, now that the police headquarters have moved to the former Inquirer/Annenberg building at 400 N. Broad.

The event, which featured live jazz music and spoken word poetry performances, is part of a series of community outreach engagements that the City hopes will give Philadelphians an opportunity to share their thoughts on what should be done with the site before it goes up for sale next year. During the event, Campbell, an actor and director with Theatre in the X, shared a poem titled Worms, which meditates on how society can create meaning from traumatic histories.

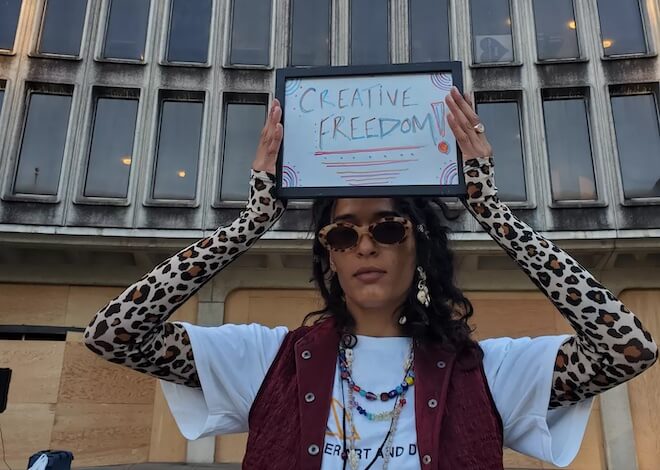

The engagement process, called Framing the Future of the Roundhouse, is trifold. It’s being led by consultants from Connect the Dots and Amber Art and Design and includes virtual surveys, individual interviews, and public events.

It’s a question of whether the City is more interested in prioritizing the desires of Philadelphians — or selling the property to the highest bidder.

“We are trying to understand where people are in relation to the site, either from a past perspective or a present/future perspective,” says Sylvia García-García, Connect the Dots’ project manager for Roundhouse engagement.

Since kicking off the process in August at Franklin Square, Amber Arts and Connect the Dots have conducted 10 public events and a number of interviews, per Framing the Future’s website. In addition to the event on the Roundhouse steps, there have been pop-ups at PCDC’s community food distribution, and youth-centered activities, with plans for more through year’s end. The outcome of this process will help determine whether or not the building should be placed on the City’s historic register.

If that happens, the building’s reuse would need to be approved by the Historical Commission. With ideas swirling and emotions running high, is it possible for the engagement process to find a solution that pleases most, if not all, stakeholders?

An ambitious building for an ambitious mission

The Roundhouse first opened in 1962. Designed by the Philadelphia firm Geddes Brecher Qualls & Cunningham, the four-level building was intended to provide a hopeful alternative to the PPD’s then-current hub in the basement of City Hall.

The building was significant architecturally: Its brutalist design is one of the first in the country to be constructed almost entirely of precast concrete. Workers assembled thousands of pieces onsite, like a giant puzzle.

Patrick Grossi, director of advocacy for the Preservation Alliance for Greater Philadelphia, calls the Roundhouse’s construction process “novel.” He says, “Whether you love the building or hate the building from a purely aesthetic perspective, it is unique. It illuminates a period and the city’s history when it was trying to reform itself … when leaders were trying to think of a more liberal way of managing a city.”

The building’s design alone was supposed to embody a new period of progressive policing. The main entrance on Race Street was to be open to the public, so people could come in and observe the police in action.

“It was about bringing the police out into the community in a more in a close, working, respectful relationship,” says Jack Pyburn, principal architect at Atlanta’s Lord Aeck Sargent and a preservationist who has advocated for maintaining the Roundhouse. He became interested in the building in the 1980s through his father-in-law, the building’s concrete precaster.

The idea that the structure could create community was flawed from the beginning, however. Completed just 12 years after the City began planning for the Vine Street Expressway, which split Chinatown, the Roundhouse became part of a series of urban renewal efforts that threatened the cohesiveness of the neighborhood, cutting residents off from Franklin Square, Chinatown’s largest green space. A few years after construction was finished, a wall around the original design further separated police from the community.

“Those urban renewal projects didn’t really help Chinatown to connect to the rest of the city and to neighborhood amenities. The land was cleared to build this public [police] headquarters,” says Yue Wu, neighborhood planning and project manager at Philadelphia Chinatown Development Corporation and member of the Framing the Future of the Roundhouse engagement advisory board. “A lot of people living in Chinatown go to Franklin Square to take walks or exercise. So that’s a really important neighborhood asset. The Roundhouse is right next to Franklin Square. It doesn’t provide an inviting environment for the neighborhood.”

The Rizzo era

Then came the rise of Police Commissioner and later Mayor Frank Rizzo. Though police brutality existed in the city before his rise and extended well after, Rizzo and his notoriously racist policing tactics came to prominence at the same time the Roundhouse was being built, forever linking the two in public memory.

During his tenure, the Roundhouse was used to hold prisoners sometimes unlawfully and sometimes without food, per a 1973 federal ruling that found police violations in Philly were so common that they could not “be dismissed as rare, isolated instances.” A 1977 investigation by the Inquirer found that when questioning suspects in the Roundhouse, the City’s homicide detectives regularly used “either physical or psychological coercion,” including beating people with lead pipes.

Ironically, the Roundhouse became the opposite of what it was intended to be.

Manuel Portillo is director of community engagement for The Welcoming Center, a nonprofit that serves immigrants in the city. He’s worked with Puerto Rican and Latino communities in North Philadelphia who remember that era — and lived in fear of the city’s police force. Portillo is also on the project’s engagement advisory board.

“People were very fearful of the police,” he says, “Community relationships were not good.”

Managing a reckoning

The process of redeveloping a building as physically and psychically imposing as the Roundhouse is a challenging one. Simply demolitioning the building, architect Pyburn explains, doesn’t reckon with its traumatic history, brutal memories embedded in Philadelphians’ minds.

“Removing the building doesn’t do anything to deal with those issues,” Pyburn says. “If anything, keeping the building deals with those issues … [because] the building can become a place of examination and reconciliation.”

And Philly isn’t alone in managing this reckoning. This spring, New York state created the Prison Redevelopment Commission as a way to engage with communities before redeveloping prisons. Their goal is to find ways of repurposing sites to meet community needs.

Even if the City eventually sells the Roundhouse to a developer who tears it down, seeking civic participation can help the City document people’s histories with the building. During in-person events, people can contribute to a public art project, take part in interviews, and tell their stories from a podium. Online and virtual engagement opportunities allow people to share more anonymously.

Connect the Dots and Amber Arts are working with social psychiatrist Mindy Fullilove to listen to and dialogue with people who were imprisoned or experienced police brutality at the Roundhouse. They’ve also started the introductory process of working with organizations, including Redemption Housing, Philadelphia Lawyers for Social Equity and Uplift Solutions, to engage with the city’s justice-impacted citizens — a term that encompasses both people who have been incarcerated and those who may have had other negative interactions with the police and criminal justice system.

We’ve done this before

This isn’t the first time Philly has had to reckon with a building’s past while trying to sell it for redevelopment.

In 1984, when the City was considering selling Eastern State Penitentiary (ESP) for commercial redevelopment, a number of locals — mostly historians, preservationists, criminologists and sociologists — came together to protest plans to turn the site into a shopping center. They argued the building’s history as a prison that changed the carceral system in the U.S. should be preserved in a way that acknowledged the trauma that occurred there.

Somewhat incredibly, the City listened — and turned it over to the activists, known as the Eastern State Task Force. This group raised funds from both The Pew Charitable Trusts and a 1991 Halloween event to turn the site into a museum and began giving tours.

As part of the organization’s mission, ESP now advocates for an end to mass incarceration in the U.S. A massive infographic erected in 2014 on the penitentiary’s old baseball diamond illustrates how America has the highest incarceration rate in the world. The museum features art exhibits created by incarcerated people. It also became a fair chance employer, creating a training program and hiring returning citizens to work in the organization.

Sean Kelley, senior V.P. and director of interpretation for ESP, isn’t sure whether the same approach could work for the Roundhouse. But a number of people think a museum dedicated to the history of police brutality could be a meaningful reuse. The Roundhouse engagement team has been in touch with Kelley’s for ideas on approaching the site’s history.

Kelley believes community engagement is the way to go. His advice: “Take your time doing this. Take your time to let the process breathe.”

A Roundhouse for justice

Most participants in the process have expressed support for keeping the Roundhouse rather than tearing it down. Many say the site should be repurposed in a way that redeems the building’s history. Ian Litwin, project manager for the redevelopment with the City’s Department of Planning and Development, says the building would need new electric and mechanical systems, but is otherwise in good condition for reuse.

Jeffrey Abramowitz is executive director of justice partnerships for JEVS Human Services and coordinator of the Philadelphia Reentry Coalition, a City-supported initiative that brings together agencies and organizations that help justice-impacted individuals. He believes the building could be used to house nonprofits like his. The over 133 justice related agencies that comprise the Reentry Coalition could use the space.

“We should try and turn [the Roundhouse] around and use it to our benefit by turning it into something that could be really useful in the justice setting,” says Abramowitz, “like use it for reentry vocational training programs, use it for educational programming, use it as a community support — really give it back to the community that was so impacted by the things that happened within those walls.”

A Roundhouse for affordable housing

Wu hopes part of the site can be converted into affordable housing to help ease the sting of gentrification in Chinatown, especially for older neighbors. More than 38 percent of Chinatown residents who are 65 and older live in poverty, compared to 17.4 percent of seniors citywide, according to the 2020 report Chinatown Future Histories: Public Spaces and Equitable Development in Philadelphia Chinatown. The Roundhouse could follow the example of Oakland, California, which recently voted to turn its former downtown police headquarters near its Chinatown into affordable housing.

But the Roundhouse’s layout — which features three, connected circles — makes it challenging to convert to residential use, Litwin says. (The closest residential property, Metroclub Condominiums across the street, has a similarly round, figure-eight shape. But, as a former hospital, that building’s inner workings are vastly different). An easier solution may be to build new affordable housing in the PPD’s old parking lot.

The best of all worlds?

At 2.65 acres and 125,000 sq. ft. of floor space, the Philadelphia Roundhouse could be redeveloped as more than one thing. A museum commemorating the history of the site and educating people about police brutality could go on the first floor. The upper floors could be converted to office space for nonprofits dedicated to helping the justice-impacted. The parking lot could be built up to include mixed-use commercial and affordable housing space.

It’s a question of whether the City is more interested in prioritizing the desires of Philadelphians — or selling the property to the highest bidder.

Don’t count them out, either. The City has recently shown a willingness to prioritize community needs in other redevelopment projects. When it sold the Family Court building at 1801 Vine Street, it required that developers submitting proposals include plans in their design for the African American Museum in Philadelphia. Four developers have been short-listed for the project, which will take several years to complete.

Could that same approach work for the Roundhouse? If the City is serious about engaging residents — about taking the perspectives from the careful and long process into account — it could find a middle ground that preserves the building and allows it to embody the progressive, community-oriented values its architects originally intended.

Does any of this work matter?

Many observers have doubts that the engagement process will inform the future of the Roundhouse. Once it becomes the property of a developer, it’s largely out of the community’s hands, unless the City includes requirements in their request for proposals from developers, as it did with the Family Court Building.

“[Conditions] can reduce the amount of money you’re going to get for the site,” he says, “But I think we’re going to balance the need for economic development with the outcomes of this process.”

Still, many feel that the City should have begun the engagement process before deciding to sell the building.“If they really truly wanted to do it right, they would have opened up the discussion before that,” Portillo says.

For his part, Campbell doubts any developer that eventually purchases the building will honor the wishes of Philadelphians detailed during the community engagement process.

“I would love for the words of the people, and the hopes of the people, and the requests of the people, and propositions that the people make to be honored by whoever gets it,” he says, “but I’m not naive enough to believe that [will happen].”

The City will continue the Roundhouse community engagement process through the rest of this year. Philadelphians can participate by filling out a survey, sharing their thoughts on the idea wall or attending an event. The next public event will take place on October 29, during the Harvest Festival at Mitzie MacKenzie Playground in Chinatown.

![]() MORE STORIES ON COMMUNITY ENGAGEMENT AND REDEVELOPMENT

MORE STORIES ON COMMUNITY ENGAGEMENT AND REDEVELOPMENT