With the release of the 2020 census block group data on Thursday, we’re now starting to get a clearer picture of the changes that could be in store in the upcoming legislative redistricting for congressional, state legislative, and City Council districts in Pennsylvania.

The big headline news is that Philadelphia finally crossed the 1.6 million population threshold after stalling in the 1.5 million range since the 1990 census—a very pleasing milestone for local boosters. The city gained 77,791 residents since 2010, and the population now stands at 1,603,797, which is the highest it’s been since 1980.

Philadelphia’s population peaked in the 1950 census, at 2,071,605 people, and continued to fall in each census until 2010. After a low point in 2000, the city grew 0.6 percent in the decade between 2000 and 2010.

In the 2010 to 2020 period, Philly grew at a rate of 5 percent, powered by growth in the Hispanic population (+50,666), non-Hispanic Asian population (+36,887) and multiracial population (+25,913). The Black and white populations both fell, by 30,452 and 11,757 respectively.

There had been a lot of understandable dread about what would happen with the 2020 census count taking place during a pandemic, led by Donald Trump’s administration, but on first pass, the results in PA and nationwide seem broadly very good for the constituencies who were thought to be most at risk of an undercount.

According to the Inquirer, “the decline in Philadelphia’s Black population—a loss of about 30,500 people—is the city’s steepest in history. The loss in the city’s white population—about 11,800 people is the smallest decline since the 1940s, when Philadelphia added roughly 14,000 white residents.”

In the coming weeks, we’ll start to get a better sense of how the population has shifted within Philadelphia in a more fine-grained way that will provide more insights for redistricting, and what kinds of demographic shifts are happening within the southeastern PA region.

Thursday’s census release officially starts the process for City Council redistricting, with a six-month countdown that ends on March 12. According to the City Charter, Council must pass a new district map by that date, or else they’ll stop being paid.

Council district populations have to be roughly equal and are only allowed to vary by up to 10 percent. Based on early calculations from our friends at Azavea, the target redistricting population for City Council districts for the new map should be around 160,378.

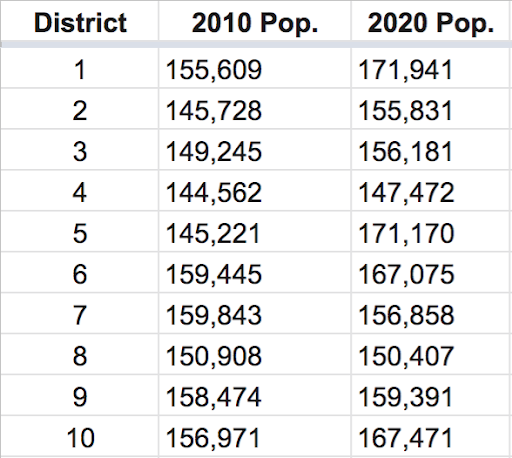

The table below shows where each of the districts stands now compared to its 2010 population.

A 10 percent variation from the smallest to largest districts would put the allowable population range for the new districts between 152,359 to 168,396. Currently, only four districts—the 1st, 4th, 5th and 8th, represented by Mark Squilla, Curtis Jones Jr., Darrell Clarke and Cindy Bass—fall outside of that range and would need to gain or lose voting divisions. There’s a Rubik’s Cube quality to this exercise, though, in that moving the lines in one direction impacts other districts’ population totals, so mostly everybody should see their boundaries shift at least somewhat. (Read our prior post about Council redistricting for more about the process.)

Pennsylvania also saw a net gain in population of 300,321 residents, for a total of 13,011,844 people. Passing 13 million residents was a big milestone for Pennsylvania too, and PA is now the fifth largest state as of 2020 after surpassing Illinois. Philadelphia makes up 12 percent of the total state population today but accounted for about 25 percent of the population growth in the Commonwealth over the last decade.

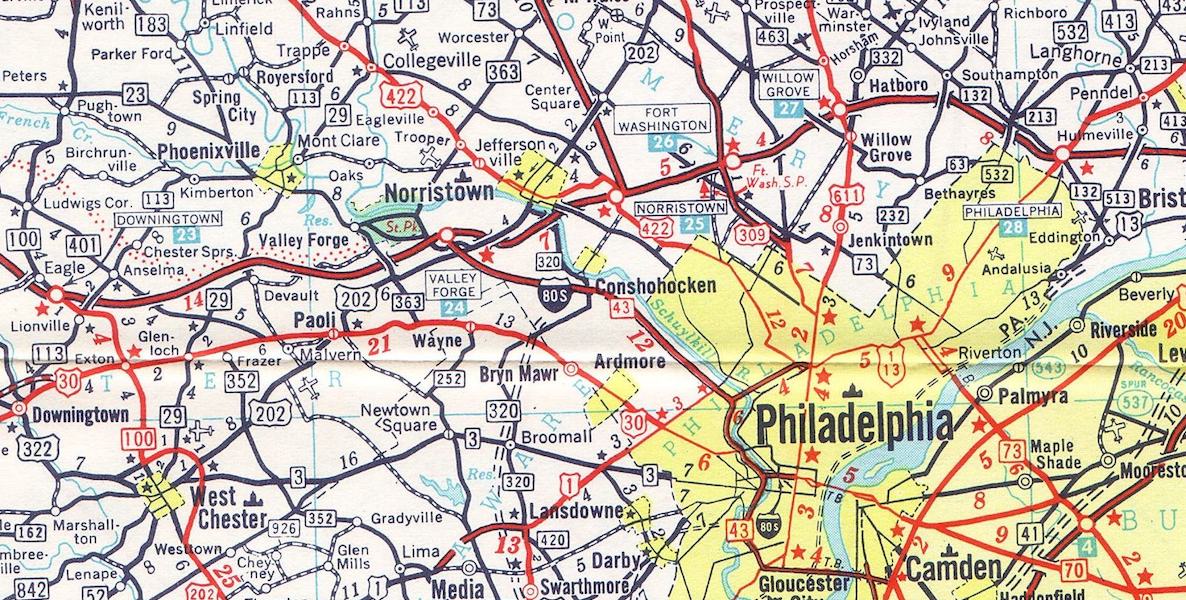

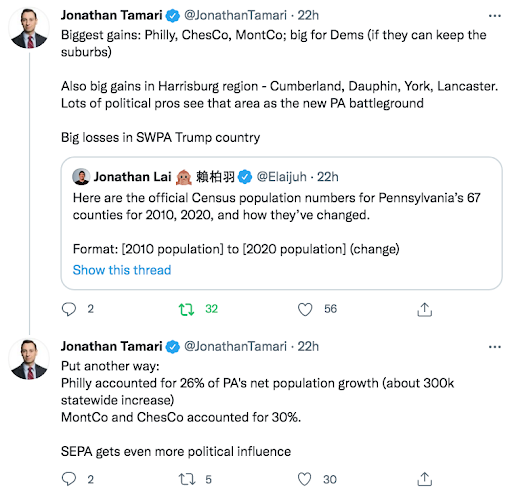

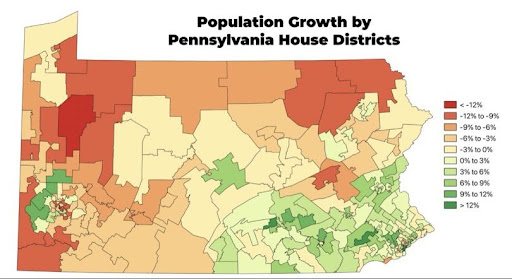

The broad trend in the population shifts by county is that Pennsylvania’s more urbanized areas in the southeastern and central regions continued to grow, while shrinking areas in the west continued to shrink. That trend is going to cause a net shift in the geography of political representation toward the southeast and central PA when state legislative districts are redrawn. Philadelphia alone grew enough to gain one state House seat in the state legislature, and with the collar counties growing by 100,000 as well, it’s possible the whole southeast could see a net gain of 3 seats in the state legislature.

(Source: Jonathan Tamari)

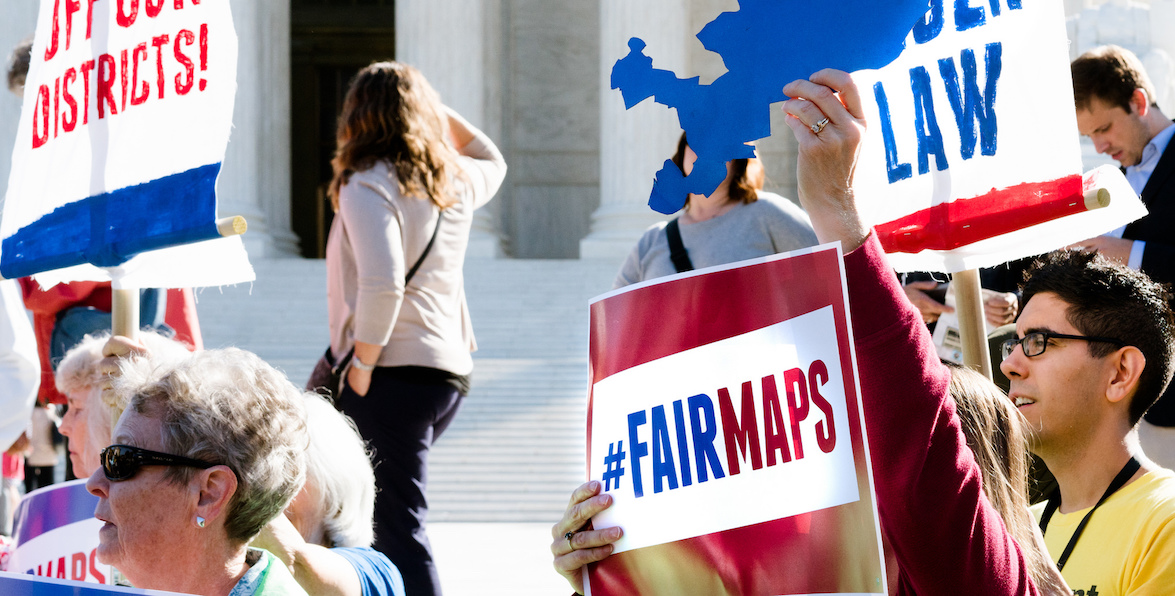

There had been a lot of understandable dread about what would happen with the 2020 census count taking place during a pandemic, led by Donald Trump’s administration, but on first pass, the results in PA and nationwide seem broadly very good for the constituencies who were thought to be most at risk of an undercount. Combined with the Democratic Supreme Court majority, the 2020 PA census population trends appear to be very good for Democrats’ chances of making gains in the state legislature in this round of redistricting.

(Map: Gianni Hill on Twitter)

Even with Pennsylvania’s modest growth—2.4 percent compared to 7.4 percent for the U.S. overall—the Commonwealth will still lose a Congressional seat in this round of redistricting due to stronger growth elsewhere. Charles Thompson at the Patriot News reminds us of the Independent Fiscal Office’s projections from last year that PA’s aging population is going to present some headwinds for future population growth if current trends hold.

Some analysts are concerned that because of Pennsylvania’s aging population, it will be even harder to maintain that traditionally slow and steady growth in the future as deaths start to outnumber births. That already happened in 2020 according to the state’s preliminary numbers, though the coronavirus pandemic may have played a role in that.

But projections run for the state’s Independent Fiscal Office last year also suggested deaths of residents will start to exceed births in Pennsylvania through the next five years, meaning Pennsylvania would have to finds ways to slow or reverse its annual net loss of residents to other states—pegged at 20,854 in 2020—or increase the number of international immigrants, a gain of 14,523 in 2020, to stay on the growth track.

It isn’t a foregone conclusion that Pennsylvania must keep losing residents to other states, however. While it’s true the population is declining in parts of the state, the southeast and central regions are growth areas and have an opportunity to continue growing in the era of more remote work, and continued cost pressures in New York and Washington. These regions feature some very nice towns and neighborhoods where lots of people would surely like to live, if only there was some more housing available.

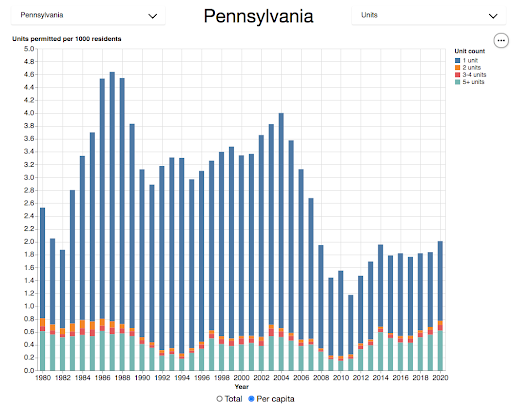

And on that front, Pennsylvania really isn’t playing to its advantages yet. Pennsylvania municipalities used to permit a lot more housing in the 1980’s through the early 2000’s, but ever since the Great Recession, they’ve been permitting significantly less per-capita.

(Chart: Sid Kapur)

State lawmakers should do everything they can to engineer a big infill housing boom in the parts of the state that people do still want to move to, especially inside the SEPTA regional rail footprint, and try their best not to lose representation for Pennsylvania in the next census in 2030, and maybe even gain a seat back.

Jon Geeting is the director of engagement at Philadelphia 3.0, a political action committee that supports efforts to reform and modernize City Hall. This is part of a series of articles running on both The Citizen and 3.0’s blog.

Photo by Governor Wolf's Office / Flickr