Growing up in Jamaica, Tesia Ledgister always helped her grandfather, who was blind.

“From the time I was young, a part of my chores was to assist him. I’ve always loved and had compassion for caring for people,” she says.

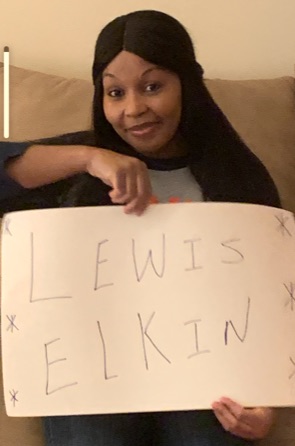

At 15, Ledgister came to the U.S., where that knack for helping others led her to a career in nursing, with an eye on tending to children—first, as a pediatric home care nurse and, since 2018, as the school nurse at Lewis Elkin Elementary School in Kensington. “I really wanted to work in a community-based setting,” says the mother of two.

And work she does: Along with the 270-plus other school nurses employed by the School District of Philadelphia, Ledgister’s role involves meeting the complex needs that are so common among families in impoverished communities: connecting uninsured families to medical care, getting services for immigrant students whose families are undocumented, addressing the effects of neighborhood violence, addiction, crime.

The pandemic has only compounded the demands placed on school nurses like Ledgister—yet, across the board, says Shannon Smith, who oversees all school nurses in her role as the School District’s health coordinator, school nurses have risen to the challenges thrown their way.

“My focus is normally how do I keep students healthy and in their seats to learn, and how do I give the nurses the resources to provide those tools to the students? With the pandemic,” says Smith, “I had to think about the fact that the students aren’t in the building, but we still need to reach them. We still need to lay our eyes on them and see if they’re safe, because some of our students are in very vulnerable situations.”

“2020 has not been a good year, and I think that we as a district have really faced each issue headfirst,”—including, she says, the unrest over rampant racism—“and not shied away from any of it.”

She wants to keep her nurses safe, too, while helping them get in touch with families to ascertain their needs.

“I had one of my nurses—I was so proud of her—standing outside of a student’s house at the window, showing the child how to count their carbs because they were a newly-diagnosed diabetic,” Smith says. The information was just too complex to explain over the phone.

Other times, nurses have called a child’s home about one issue, only to learn that the family was, say, hungry and needed food; in cases like those, nurses have immediately pivoted, tapping into their extensive networks of community resources to get families’ needs met.

“My nurses amaze me every day,” Smith says.

They do not choose their line of work for recognition—but school nurses are the unsung health heroes of the pandemic.

Planning ahead

Smith remembers the last day she was in her office, on March 13.

“The day we were sent home, [administration] said ‘Take your laptop, you might be out for two weeks.’ And we have literally been working on Covid-19 planning since that day,” she says.

CHOP’s PolicyLab, CDC, and Philadelphia Department of Public Health have guided every aspect of planning, and Smith credits the District for taking a holistic approach to student health, addressing needs from food insecurity (with food pickup sites) to mental health support (with initiatives like Healing Together, which addresses social-emotional learning, mental health and trauma, adult wellness and community resources).

“I was really proud that they left no stone unturned,” Smith says. “2020 has not been a good year, and I think that we as a district have really faced each issue headfirst”—including, she says, internet access and the unrest over rampant racism—“and not shied away from any of it.”

The system has laid a supportive foundation, but the day-to-day efforts of school nurses cannot be minimized.

Nurses have helped parents who, during the pandemic, have been unable to get their children life-saving insulin and inhaler refills, dental treatments and eye care. At a time when trying to make an appointment for a medical visit can eat up hours in aggravating hold-time, nurses are spending their days making calls on behalf of families—to St. Christopher’s, to CHOP, to medical practices and clinics throughout the city.

When, at the start of the school year, a student at Elkin was tragically killed in a car accident and the school community couldn’t come together in-person to grieve, Ledgister, along with her school’s counselor and principal and climate staff, went out into the community to check on and be there for families, to help them through their shock and pain.

Answering the call

![]() Nurses are also playing a key role in keeping kids eligible for school.

Nurses are also playing a key role in keeping kids eligible for school.

This week marked the deadline by which all children needed their required immunizations; any student who is non-compliant with immunizations will be marked with an unexcused absence, daily, until their immunization records are updated.

Following 10 unexcused absences, a student is considered truant—if schools were operating in-person, students would not be allowed into the school building; in the digital setting, however, they actually can still attend class without being kicked out or banned from learning.

When the school year started in September, 9,000 District students were behind on their required immunizations; since then, school nurses have brought that number down to 4,400, through sheer dedication.

For a lot of these students, the nurses are someone they can trust. Someone that, when they’re in need, sometimes they feel more comfortable coming to you and expressing to you their feelings, and what’s going on.”

“What’s worked at my school is consistency and teamwork with my social worker, my principal, and my vice principal,” Ledgister says. “They assist me with the resources that I need, particularly when working with a dual-language population”—like a District-provided interpreter, and the Language Line, which provides communication in more than 200 languages.

Ledgister has also given families her personal phone number, and takes calls from parents at night, on weekends, or whenever they get around to sending her their children’s vaccination records or calling to ask questions about them.

SDP recently announced a partnership with CVS, which will create 24 vaccination centers on school sites throughout the city. But, as CVS is a for-profit company, only students with insurance will be eligible for them.

![]() Approximately 70 percent of SDP students have health insurance, though this figure is hard to firmly quantify, as undocumented families are, understandably, reluctant to share their status with District and City agencies.

Approximately 70 percent of SDP students have health insurance, though this figure is hard to firmly quantify, as undocumented families are, understandably, reluctant to share their status with District and City agencies.

For those who are uninsured, school nurses will continue to spend hours doggedly arranging alternative opportunities to get shots: scheduling appointments at one of the city’s 10 health centers or at federally-qualified health centers, of which there are also about 10, and working with Public Citizens for Children and Youth (PCCY), a group Smith calls “a wonderful, wonderful [nonprofit organization] that goes above and beyond” in its refusal to turn away undocumented immigrant children whose families are ineligible for insurance.

Gone is the era of the stereotypical, Norman Rockwellian provider-of-Band-Aids. Our nurses work with social workers, pediatricians, the Office of Family and Community Engagement, in many ways playing the role of a nurse-navigator, or health quarterback.

Forging bonds

Ledgister, whose students affectionately call her “Ms. T,” says that so much of school nursing is about trust.

“What a lot of people don’t know about school nurses is that we are, for most students, their go-to person. For a lot of these students, the nurses are someone they can trust. Someone that, when they’re in need, sometimes they feel more comfortable coming to you and expressing to you their feelings, and what’s going on.”

Smith also values the role school nurses get to play in educating students. Having worked for 20 years as a high school nurse, she was a key point of contact for teens. “A lot of times I would just chip away at students’ crazy preconceived notions, and I actually saw how it made a difference. That really intrigued me, and I loved it,” she says.

Ledgister says she’s often asked by people who know how challenging her role is why she doesn’t apply to transfer to another one. “I’ve been here for more than two years, and I just love my kids. I wouldn’t change it. I wouldn’t leave. This is where I want to stay.”

Covid challenges and all, Smith says that the kind of nurses who work in school environments embrace wearing many hats. “We are PCPs [primary care providers], we are the ER, we’re psychologists sometimes, we’re social workers, we’re the parent when the parent isn’t here, and we’re very, very strong advocates for kids. It all boils down to removing barriers to learning.”

And whether kids are in classrooms or behind computer screens, that’s exactly what Philly school nurses will continue to do.

Says SDP Superintendent Dr. William R. Hite, “Nurses have done a tremendous job of understanding what is needed and the protocols that must be in place. They have been extraordinary throughout this process.”

Photo by Rusty Watson/Unsplash