Say what you will about former President Donald Trump’s approach to climate policy. If nothing else, his 2017 withdrawal from the Paris climate agreement spurred Mayor Kenney (and 61, and, eventually 350, other U.S. mayors) to act locally.

Three months after Trump’s announcement, the City of Philadelphia announced its Municipal Energy Master Plan for the Built Environment. The plan set three goals for 2030, along with a commitment to reduce or maintain energy costs for the city’s built environment. Those goals were:

- Reduce emissions from City-owned buildings by 50 percent.

- Reduce built environment energy use by 20 percent.

- Transition the City to 100 percent renewable electricity.

Then, in 2021, the City doubled down on its commitment to fighting climate change. Kenney promised to zero out carbon emissions — to go “net zero” — by 2050. His Climate Action Playbook outlines the plans the City has in place for Philly to reduce emissions and adapt to the effects of climate change. (Of course, City of Philadelphia regulations are, in some cases, subordinate to state and federal regulations.)

That is more important now than ever. And scientists have stated there needs to be a 25 percent reduction in carbon emissions by 2030 and peak greenhouse gas emissions by 2025 to secure a livable future. By the end of his term Trump had ambushed over 100 environmental rules, and President Biden’s climate goals have been declared almost dead. That makes what happens at the local level paramount to protecting the earth.

For real, lasting progress, we’ll need radical change at every level of society — the foods we eat, the ways we travel, the houses we live in.

“There is no silver bullet,” says LeAnne Harvey, program and policy director for Green Building United, a nonprofit that works to advance green construction regionally. “We can prioritize initiatives based on expected carbon savings, but in order to reach our local, regional and global targets, we have to do everything, all at once. That includes rapidly transforming our transportation sector, better managing our lands for carbon sequestration, building out a circular economy, and more.”

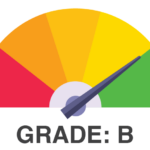

Nearly five years after the Municipal Energy Plan was released and almost one year since debuting the Climate Action Playbook: How are we doing?

The short answer: We’ve made some progress. But we must do better.

Here’s where we are on Mayor Kenney’s climate goals

Goal: Reducing carbon emissions from buildings and industry by 50 percent

At the core of the 2017 municipal energy plan are the 600 buildings the City owns and operates. And for good reason: That year, energy use by all Philly buildings and industry accounted for 75 percent of our carbon pollution, per the Climate Action Playbook.

The City’s municipal energy use dashboard shows we’re on track to meet many of the goals outlined in the 2017 plan. That comes with a couple caveats: Much of the success is the result of shifting away from coal to natural gas, so though we’ve seen a drop, that won’t continue long-term unless we shift toward cleaner forms of energy like renewables. And the success so far has only been of municipal buildings; what is still needed — and only just now getting underway — is a City-led push for private buildings to reduce their carbon emissions as well. (More on that below.)

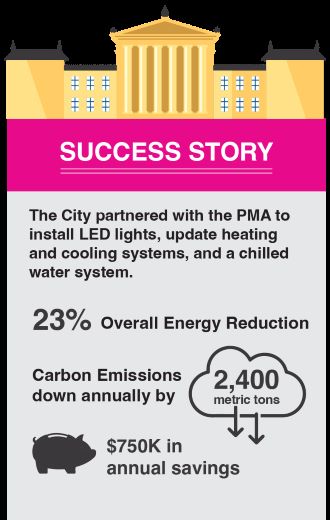

One success story: A deep energy retrofit in 2020 for the Philadelphia Museum of Art, one of the city’s top five municipal energy users. The City partnered with the PMA on the $11.3 million project, which included installation of LED lights, updated heating and cooling systems, and a new chilled water system. The project reduced the museum’s overall energy use by 23 percent, brought down its yearly carbon emissions by 2,400 metric tons, and is expected to save the museum $750,000 per year.

In 2021, the City also completed a project to update HVAC and lighting systems in the Fire Administration Building, which brought the building’s total energy use down 34 percent from April 2021 to March 2022. (These changes have yet to be reflected in the city’s latest emissions data.)

All told, by 2020, the City had exceeded its interim goal of reducing carbon emissions from the 2006 baseline by at least 10 percent. The latest citywide greenhouse gas emissions inventory, released in April, showed that between 2006 and 2019, overall emissions had dropped 20 percent.

We’re also on track to meet the next goal — a 25 percent reduction by 2025. Emissions from City-owned buildings alone went from 219,306 to 133,527 metric tons of carbon.

Emily Schapira is president and CEO of the Philadelphia Energy Authority (PEA), the municipal authority that contracts with the City for large energy projects. She says the PMA upgrade “really set the tone for cultural institutions all across the country” and that the City’s overall progress has “created a model that is a national model. People are looking to Philly to see how this gets done.”

Harvey of Green Building United agrees — somewhat. “Progress is slow going, but they are inching along,” she says.

Reducing emissions solely from City-owned and operated buildings won’t meet the City’s ambitious goals, however. Commercial and residential buildings will also need to make changes to be more energy efficient. “The City has done what it could, given the resources that it has, but these plans need to be far stronger if we want to truly move the needle on climate change and energy security,” Dr. Simi Hoque, professor and program director for the department of civil, architectural and environmental engineering at Drexel University, says in an email.

Hoque and 15 other Drexel professors authored “Climate Change and the Future of the North American City,” a sprawling report that examines how climate change will impact everything from storm activity to public health and air quality in Philly in the year 2100.

The PEA’s Commercial Property-Assessed Clean Energy (C-SPACE) program aims to incentivize property owners to make their buildings more energy-efficient by offering loans to help finance upgrades, water conservation and clean power projects. As projects are completed, PEA publishes the results on their site. So far, nine projects have been completed, including one at 100 S. Independence Mall West that reduced CO2 emissions by 10,048 metric tons. (Ithaca, New York, has taken this one step further by creating a public-private partnership to finance low-interest loans, one way to increase the availability of resources for private building owners.)

The City also created a Building Energy Performance Program in 2019, which mandates that non-residential buildings with at least 50,000 square feet of indoor floor space conduct building tune-ups aimed at increasing energy efficiency and water conservation. (Tune-up reports are due over the next couple of years, depending on size of the buildings.)

Again, Hoque says, that’s a start — but it does not go far enough to really solve the problem.

“We should focus first on anchor institutions and large commercial properties, rather than small businesses,” says Hoque. “The goals we set should be aggressive and accountable. There should be fines for not meeting these goals, similar to the fines that an industry has to pay for polluting the air or water.”

Goal: Reducing energy use by 20 percent

Both the City’s electricity and primary heating consumption have decreased from the 2016 baselines the Municipal Energy Master Plan uses to track its progress.

Electricity consumption is down from 281,324 weather normalized megawatt-hours (MWh) to 274,481 weather normalized. For reference, the 2030 goal is 225,059 weather normalized MWh. Primary heating consumption (typically powered by gas) went from 828,532 weather normalized Metric Million British Thermal Units (MMBtu) to 760,556 weather normalized MMBtu. The goal is 662,825 weather normalized MMBtu by 2030. (Weather normalized measurements are used to create accurate comparisons between places, or years in this case, with different weather conditions).

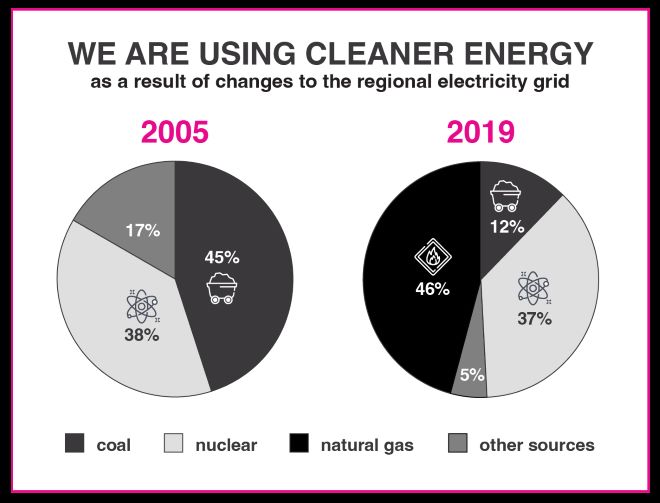

And the energy we are using has gotten cleaner as a result of changes to the regional electricity grid. In 2005, the Reliability First Corporation East (RFCE) grid subregion, which supplies Philly’s electricity, got 45.09 percent of its power from coal and 38.31 percent from nuclear energy, WHYY reported. Data from 2019 shows natural gas in the number one spot, supplying 45.7 percent of the grid’s power needs. Nuclear power remains in second, at 36.95 percent, and coal has fallen to third at 12.34 percent.

The City may not control the grid, but this trend has had a positive effect on Philadelphia’s emission’s rate because natural gas releases less carbon when burned than coal. Still, natural gas, which is mostly methane, has additional environmental risks: Fracking, water contamination and potential explosions. And natural gas’s long-term effects are still disastrous — methane molecules trap heat in the atmosphere about 90 times more effectively than carbon dioxide, National Geographic reported in 2020.

Staffing issues have affected the city’s ability to make progress on its energy use goals, according to Dominic McGraw, energy manager for Philly’s Energy Office. But he says a proposed increase to his office’s capital budget for fiscal year 2023 could allow it to support more initiatives. “Our office is currently hiring, but just like, with all the turnover, it’s just really hard to keep projects going,” he says.

The city’s LED streetlight conversion is one area that has struggled with a lack of staff. Schapira says that the PEA stepped in to help support the plan to convert 100,000 streetlights to energy-efficient LED bulbs, reducing our carbon footprint by nine percent. “That might have previously been more driven by the Energy Office, but we put a project manager on this when we realized they didn’t have the staff to keep it moving,” Schapira says.

Then, there’s Philadelphia Gas Works. PGW, the largest municipality-owned utility in the country, contributes almost one fifth of Philly’s carbon emissions.

In December, the Office of Sustainability released its PGW Diversification Study, exploring ways the utility could go carbon-free. The energy office is currently seeking funding to begin a networked geothermal pilot study based on the recommendations from the report. (Geothermal is a kind of renewable energy that uses heat produced within the earth to warm homes and generate electricity.)

Some have accused PGW of actively working against these goals. Last November, PGW and the National Parks Service reached a behind-closed-doors deal to replace steam heat in Independence National Historical Park buildings with natural gas boilers. The City-owned utility also advocated for Senate Bill 275, which would strip the City of its right to choose how to decarbonize.

Philly will need PGW to fundamentally change — and not just talk about it — if we’re going to do our part to combat climate change.

Goal: Generate or buy all electricity for City buildings from renewables by 2030

Renewable energy sources still trail far behind nuclear and natural gas in the region’s electric grid. In 2016, the year currently used as a baseline for the municipal energy use dashboard, renewables accounted for just six percent of the City’s power use sources. By 2019, that number had only increased to eight percent. The goal, again, is to generate or purchase 100 percent of the electricity for the City’s built environment by 2030.

“I’m not a math major, but if they need to get to 100 percent in eight years, that doesn’t feel on track,” says David Masur, executive director of PennEnvironment, a nonprofit environmental advocacy group.

In 2018, the City announced plans to purchase 22 percent of the electricity needed for city buildings from a planned 80-Megawatt array in Adams County, Pennsylvania, then being developed by the firm Community Energy, Philly Voice reported. The expected completion date was October 31, 2020.

But the project changed hands in February 2020 when ENGIE, an independent power producer and project developer, took over for Community Energy, Inc, per reporting from Green Philly. Then came the pandemic and ensuing supply chain issues.

“The project just never got started on construction,” says Schapira, who reports the array will again change developers. Now, Energix Renewables, a firm based in Arlington, Virginia, will be building the project. The new estimated completion date is December 2023. The project is expected to provide some electricity for City Hall, the Philadelphia International and the water department at a rate of $44.50 per megawatt hour for the next 20 years in accordance with the original 2018 agreement, the Philadelphia Inquirer reported.

The City is still exploring options for where to source the other 78 percent needed to reach 100 percent renewable electricity by 2030. They’re currently working to install a small solar facility at the Northeast Philadelphia Airport to generate a portion of the clean power needed to meet their goals.

Goal: Converting to clean transportation

After buildings and industry, The Climate Action playbook reports that transportation is the highest source of carbon emissions in Philadelphia, accounting for 22 percent of the city’s carbon footprint.

The City says it has prioritized initiatives that encourage people to use public transit and carbon-free forms of transportation, including walking and biking to address these emissions, as well as to meet the Vision Zero goal of reaching zero traffic fatalities by 2030.

What does that “prioritization” look like? Last year, the City installed six miles of protected bike lanes and they have plans to install an additional three miles “in the near future.” Advocates have called for policies that support pedestrians as a way to improve air quality. But endless battles — like the one currently being waged over the proposed redesign of Washington Avenue — aren’t doing anything to help get cars off the road or to prevent accidents. Traffic fatalities are actually increasing. In 2020, 156 people died as a result of traffic violence, per the City’s 2021 Vision Zero annual report. That’s an 82 percent increase compared to the last five years.

Meanwhile, the Philadelphia Transit Plan explores ways to improve public transit and electrify SEPTA’s bus fleet. Emissions from Amtrak and SEPTA trolleys, subways and regional rail have dropped due to the changes that have made the region’s electricity grid cleaner. In 2006, passenger rail emissions were 243,265 metric tons of CO2. By 2019, that number dropped to 152,941 metric tons, the 2019 greenhouse gas inventory found.

Despite these changes, the inventory found that in 2019 overall transportation emissions were up five percent from the 2006 baseline. Higher emissions from motor vehicles and airlines likely contributed to this increase. Emissions from cars and trucks went up from 3,303,724 to 3,696,421 metric tons of CO2, while airline emissions increased three percent, per the inventory. And SEPTA ridership has continued to decline. In 2021, ridership decreased by 10 million people, the Philadelphia Business Journal reported in February.

The City plans to address these emissions with the Municipal Clean Fleet plan to transition more than 6,000 City-owned vehicles to clean and electric alternatives. They plan to procure 100 percent electric sedans, SUVs, vans and light duty pickups by 2030.

On the residential vehicle side, the City has taken a step back when it comes to encouraging people to swap out gas cars for electric. Back in 2018, City Council ended a program that issued permits so that electric vehicle owners could install charging stations on sidewalks near their homes after people complained that neighbors with EVs essentially got their own, reserved parking spaces on the street. At the time, the City planned to replace the program with an indeterminate plan to install publicly available alternative charging options, but as of 2021, no action had been taken. (Some private businesses are filling in the gap, like Wawa.)

Goal: Reducing emissions from waste

Waste was the third-highest source of emissions in Philly, accounting for three percent of carbon emissions, per the Climate Action Playbook. As trash decomposes in landfills, methane is released into the air, so reducing waste both through recycling and cutting down on the amount of trash overall can have a significant effect on carbon emissions.

The greenhouse gas inventory found that Philly has almost halved emissions from waste from 1,166,947 in 2006 to 556,174 metric tons of carbon in 2019. But we’re up from 2014, when waste accounted for 466,829 metric tons of carbon. Philadelphians were also recycling 2.6 times more waste in 2017 than they were in 2007, the report found. The Department of Sustainability is currently piloting several circular economy programs with SmartCityPHL.

The Zero Waste and Litter Action Plan city government released in 2017 outlined 31 recommendations to get Philly to a zero-waste, litter-free city by 2035. But we’ve faced a number of roadblocks on the path to reaching those goals.

Illegal dumping and littering are two of the main forms of improper waste disposal that plague Philly’s streets. In 2019, we had two good, potential solutions to these problems: an algorithm Penn developed to catch illegal dumpers and Glitter, an app created by MilkCrate CEO Morgan Berman that allows residents to report litter sightings.

Then came Covid budget cuts. The City eliminated the Zero Waste and Litter Cabinet and Litter Czar Nic Esposito’s position in June of 2020. These efforts are now housed under the Office of Sustainability. Funding for Glitter, which had made it into the Philadelphia Streets Department’s FY2020 budget also slipped through the cracks, as the city focused on the mechanical street sweeping pilot program.

“Our waste stream has a huge carbon footprint,” Masur said. “It feels like even in a big D democratic city, where you know everybody loves to talk about the Green New Deal …we’re fighting rollbacks and rarely see profound policy proposals at the municipal level that would really make deep cuts into our carbon footprint as a city.”

Another underutilized opportunity to reduce emissions from waste: composting. Nationwide, between 30 to 40 percent of the food supply is wasted, per estimates from the USDA. Composting food waste lowers emissions by sequestering carbon in the soil and preventing methane emissions that would occur if the food decomposed in a landfill.

The City’s Community Composting program, announced in 2019, was delayed for a year due to the pandemic. Last year, 12 community composting sites were opened for groups who applied to be part of the pilot program and in September compost pickup was introduced at 30 rec centers, per WHYY’s report.

Private companies like Bennett Compost and Circle Compost are trying to create opportunities for residential composting where the City has fallen short, but there’s still more to be done.

Goal: Using nature to fight pollution

One solution to reduce pollution the City is championing is using nature to reduce pollution citywide. The Climate Action Playbook reports that only 20 percent of the city is tree canopy — covered in trees when seen from above — but 49 percent of our public spaces have the potential to include more if the right changes are made. “Trees play an important role in climate work, both sequestering carbon in the ground and helping the City be more resilient against extreme heat and flooding,” Knapp says.

In 2011, the Parks and Rec Department launched TreePhilly, which strives to make 30 percent of every Philly neighborhood is tree canopy by 2025. So far, it’s given city residents 22,000 trees. But in recent years, Philly has lost tree coverage. Our tree canopy declined six percent between 2008 and 2018, a City of Philadelphia and University of Vermont Spatial Analysis Lab study found. (Some residents have hesitations about tree plantings, including misconceptions that trees damage sewer lines, costs and other barriers.)

In October 2020, the City launched its first-ever urban forest strategic planning process, the Philly Tree Plan, to outline ways Philly can increase canopy and protect mature trees. The final plan is due out this summer.

Goal: Adapting to climate change

Even if Philly achieves all of the goals city government has laid out, we will still experience — and already are experiencing — some effects of climate change. Higher temperatures and more precipitation will likely be a part of our future, as we have seen over the last couple of years.

These effects are disproportionately affecting people of color and those living in poverty, largely due to past racist housing policies. Redlined Philadelphia neighborhoods have average daily temperatures almost 10 degrees higher than non-redlined neighborhoods, according to a January 2020 study published in the journal Climate. Philly’s Heat Vulnerability Index found that some neighborhoods can be up to 22 degrees hotter than others.

One bright spot: As the City considers how we need to adapt to the effects of climate change, it’s keeping its most vulnerable residents at the center. In February, it introduced its first Environmental Justice Advisory Commission and plans to start an environmental justice micro grant fund later this year.

“This launch was years in the making, and a recognition that those most impacted by climate risks and other environmental burdens are communities of color and low wealth communities,” Knapp says. “If we are to truly build a more resilient future, we have to address the past harms that have created these conditions and find solutions that can help repair trust.”

The City has also partnered with the PEA to help energy-burdened households install solar panels and make home improvements to reduce energy costs. PEA’s Solarize Philly has helped around 900 businesses and residents transition to solar-powered energy, and its Built to Last program helps the 75 percent of energy-burdened low-income households make needed upgrades that help save on energy costs.

Schapira says PEA is working to reduce poverty by training people for green jobs, like solar panel installation, since these positions pay a living wage and don’t require a college degree. Two programs run by PEA, Bright Solar Futures at Frankford High school and the Green Retrofit Immersive Training program for adults, seek to address this issue.

The Citizen co-published this story with Green Philly as part of Broke in Philly, a collaborative reporting project on solutions to poverty and the city’s push towards economic mobility. Follow Broke at @BrokeInPhilly.

![]()

RELATED CLIMATE CHANGE SOLUTIONS FROM THE CITIZEN

Ideas We Should Steal: Raising School Funds through Solar Power

Illustrations by Jane Puttaniah