In Philadelphia, the recidivism rate for those recently released from prison is north of 65 percent. A study has found that, on a national scale, more than 75 percent of ex-offenders are rearrested in the five years after their release. There are plenty of factors that go into these awful statistics: Lack of mental health infrastructure for former prisoners. Lack of career counseling upon release. Unfair terms of parole.

But one of the main drivers behind rearrest is simply desperation. For want of a job, a loan or any small opportunity, many people with criminal records have to deal with the fact that background checks will show the charges they’ve garnered for the rest of their lives, and often result in rejection.

Penn Law’s Criminal Record Expungement Project website lays it bare: “Criminal and arrest records pose an almost insurmountable barrier to securing employment, housing and public benefits for tens of thousands of Philadelphians, especially among the city’s poor, black, and Latino populations.”

“One in five people in Philadelphia has a criminal record,” says Courtney Bowles, co-founder and co-director of the People’s Paper Co-Op. “Everything you’re charged with, whether or not you’re convicted, stays on your criminal record.”

“One in five people in Philadelphia has a criminal record,” says Courtney Bowles, co-founder and co-director of the People’s Paper Co-Op. “Everything you’re charged with, whether or not you’re convicted, stays on your criminal record.”

The People’s Paper Co-Op, based at the Village of Arts and Humanities, was founded in Philadelphia in 2014 by Bowles and Mark Strandquist, artists, originally from Virginia, who have long been involved in the reentry and expungement movement. Originally set to be a five-month project, the co-op was so successful that it’s been running ever since. It operates primarily as a means to help those with criminal records in the city expunge what they can of their criminal records, with the aid of local law organizations like Philadelphia Lawyers for Social Equity. The Co-Op partners with these organizations to turn free regular expungement clinics into public events.

“We try to tell them, straight up, what can and can’t be expunged,” says Bowles.

Not everything can be pulled off of a criminal record by expungement—misdemeanors are difficult; felonies impossible without a pardon from the Governor. What can be expunged are summary offenses, charges that did not result in a conviction, those that resulted rehabilitative disposition, and some to which defendants pleaded guilty or no contest. The results can lead to a dramatic reduction of a person’s rap sheet. “I’ve seen a criminal history go from eight pages to two pages,” says Strandquist.

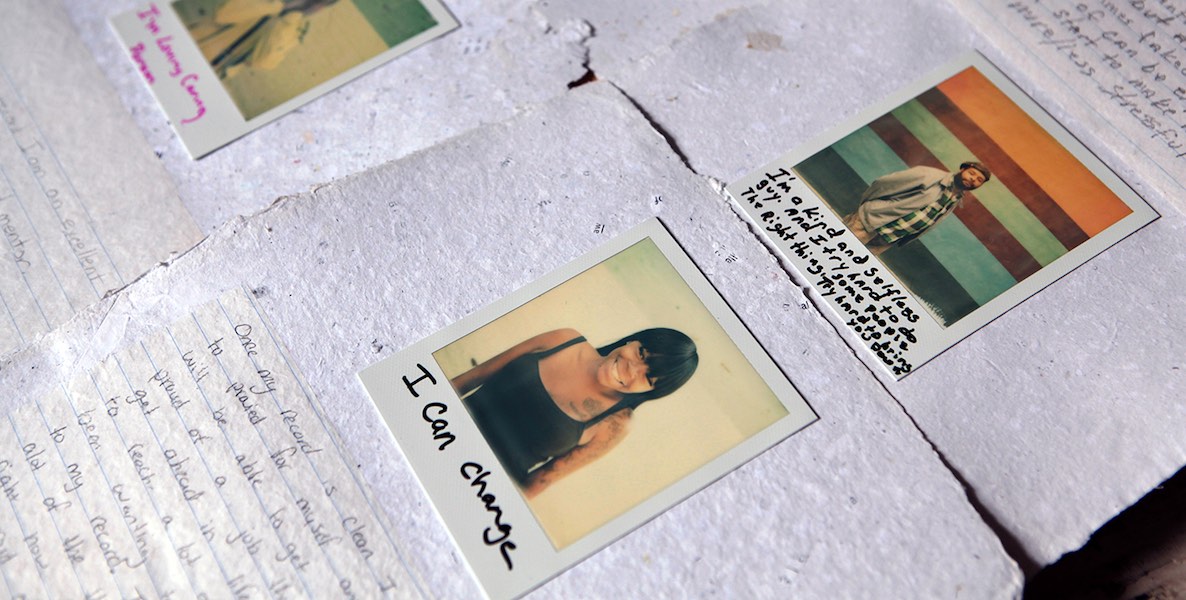

The co-op also focuses on working art into the expungement and criminal reentry process, offering a pretty visceral take on the whole thing: Once participants expunge their criminal record, they can stuff the damn thing in a blender and shred it straight to hell. Participants, after making a “paper smoothie” as Strandquist calls it, are then invited to write about what their lives would be like without all of those charges on a new, fresh sheet of paper, made from the liquefied old rap sheet.

“It’s very cathartic,” says Bowles. “Even when people can’t get much expunged, they’re still like ‘Where’s the blender?’”

“It’s a literal and symbolic transformation,” she adds. So far, the People’s Paper Co-Op has worked with Philadelphia Lawyers for Social Equity to help more than 1,000 people expunge their criminal records.

That’s become standard operating procedure for the People’s Paper Co-Op. Now, they’re working on something bigger: The Philadelphia Reentry Think Tank. The program, captained by the Philadelphia Reentry Coalition but spearheaded by the People’s Paper Co-Op, is an extensive, ambitious attempt at promoting a more prominent voice for Philadelphians with criminal records.

![]() The program sponsors fellows—Philadelphians with criminal records and experience with reentry and expungement organizations—and pays them hourly wages to help create art and written pieces to develop what Strandquist calls a “poetic Bill of Rights,” detailing the struggles and aspirations of those who have the millstone of a criminal record hanging from their neck. The Bill of Rights will be presented to to the Philadelphia Reentry Coalition’s network of stakeholders—individuals and organizations that are among the coalition’s supporters, including the Pennsylvania Department of Corrections, the U.S. Attorney’s Office and the Mayor’s Office of Community Empowerment and Opportunity—to “directly engage” them and make the case for further support and funding. Strandquist says that there are currently more than 100 stakeholders.

The program sponsors fellows—Philadelphians with criminal records and experience with reentry and expungement organizations—and pays them hourly wages to help create art and written pieces to develop what Strandquist calls a “poetic Bill of Rights,” detailing the struggles and aspirations of those who have the millstone of a criminal record hanging from their neck. The Bill of Rights will be presented to to the Philadelphia Reentry Coalition’s network of stakeholders—individuals and organizations that are among the coalition’s supporters, including the Pennsylvania Department of Corrections, the U.S. Attorney’s Office and the Mayor’s Office of Community Empowerment and Opportunity—to “directly engage” them and make the case for further support and funding. Strandquist says that there are currently more than 100 stakeholders.

“We’re trying to prove that this kind of initiative is really worth while,” says Strandquist of the Think Tank. “It’s more important, more helpful and probably more effective to involve people with direct experiences in policy conversations.”

After the Bill of Rights is brought before the stakeholders, it will be brought before the government: The Reentry Think Tank plans to hold a public event at City Hall, where their new bill of rights will be read aloud. People’s Paper Co-Op hopes that the Think Tank project will spur city government investment in more reentry programs. The date for the Reentry Think Tank’s public action has not yet been announced.

While not everything can be pulled off of a criminal record, the results can lead to a dramatic reduction of a person’s rap sheet. “I’ve seen a criminal history go from eight pages to two pages,” says Strandquist.

Strandquist says that the co-op takes a different approach to its handling of expungement and reentry, because many programs that revolve around bringing former prisoners back into common society are focused on one-size-fits-all rules meant to help reform them. Conversely, the goal of the co-op is to listen to the needs and opinions of the people attempting to reintegrate and to try give them a voice within the system. While the Co-Op is primarily focused on helping ex-prisoners expunge their records, it also seeks to include them in finding innovative ways to help them avoid rearrest; the same ex-prisoners are involved in nearly every level of the Co-Op’s mission, from drafting policies to creating workshops.

“We’re treating these people as experts, rather than as people without something to offer,” he says.

But how does the co-op measure success when facing down such a massive task as defending ex-offenders?

“You hear people say things like ‘I feel more like myself than I have in years.’ It’s about creating a space where they’re given a platform to amplify their voices. It’s a bunch of small successes that add up,” says Bowles.

Clarification: A previous version of this story indicated that the People’s Paper Co-Op organized the expungement clinics; actually, the Co-Op works with volunteer lawyers who have free clinics around the city.

Header photo by Mark Strandquist of the People's Paper Co-op