![]() This spring, as the pandemic was just beginning to ramp up in Philly, chefs and South Philly Barbacoa owners Ben Miller and Cristina Martínez received a call from friend and fellow chef Aziza Young, asking to use the kitchen at their El Compadre restaurant for a project in which she would prepare meals for elderly and low-income people in Philadelphia.

This spring, as the pandemic was just beginning to ramp up in Philly, chefs and South Philly Barbacoa owners Ben Miller and Cristina Martínez received a call from friend and fellow chef Aziza Young, asking to use the kitchen at their El Compadre restaurant for a project in which she would prepare meals for elderly and low-income people in Philadelphia.

Young, who is a private chef, had received money from one of her clients to fund the initiative and had devised a system through which she would collaborate with a different chef each day to produce 80 restaurant-quality meals for people struggling with food insecurity.

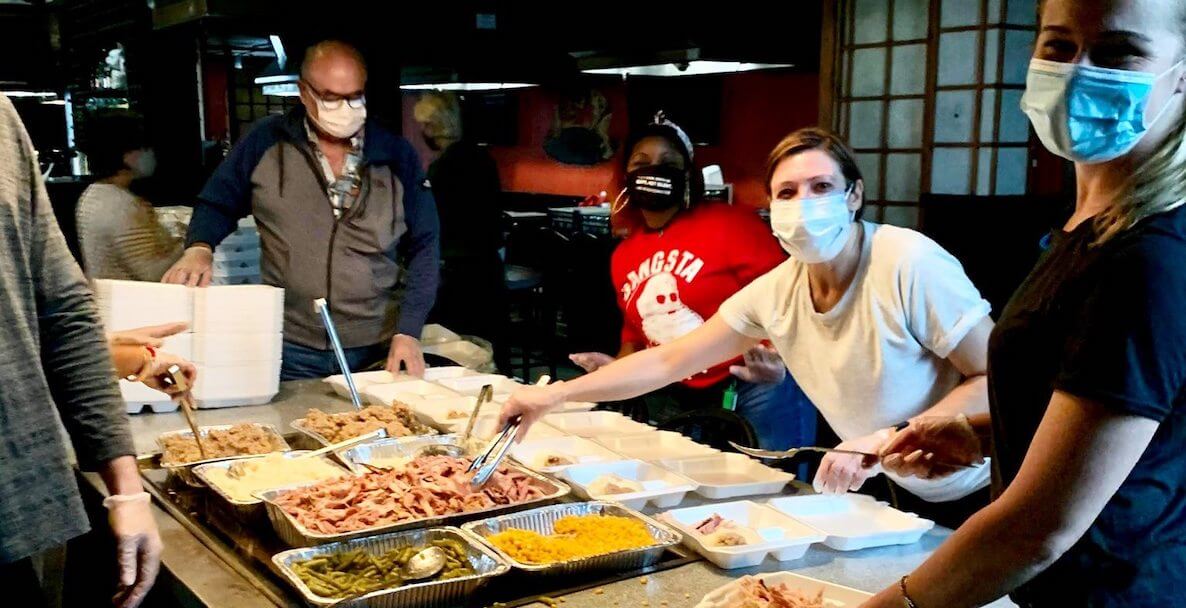

Now, the kitchen at El Compadre has become The People’s Kitchen, an organization dedicated to serving free, chef-cooked meals to hungry people in Philadelphia using the system that Young devised. Miller and Martínez have partnered with 215 People’s Alliance (215PA), a community organizing group, and together they have worked to serve 215 free meals per day while educating people about food justice issues in the city.

“We’re not just handing someone a meal, we’re inviting them into our work, and inviting them into our political education process and building local power together. The meal is the beginning of a deeper relationship that we’re hoping to build together,” says Carly Pourzand, a member of 215PA and The People’s Kitchen’s project coordinator.

Teamwork makes the dream work

Young initially reached out to Miller and Martínez about using the El Compadre space to prepare meals for a two-week period. But there was so much interest, that Miller and Martínez decided to keep the project going. El Compadre, which was owned by Martínez’s son, Isaías Berriozabal-Martínez, until his death, had been closed since 2018, leaving the couple looking for a new way to use the space.

In April, Miller received a grant from the hunger-relief nonprofit World Central Kitchen, which gave the group the funding they needed to become more established. Soon after, they partnered with 215PA, a group that Miller and Martínez were already members of prior to The People’s Kitchen. Both groups have a hand in every part of the process, but the partnership allows Miller and Martínez to focus on coordinating chefs and sourcing food while 215PA helps coordinate volunteers and focuses on the community organizing aspects.

“We’re making chef-prepared, very high-quality hot meals and I think that’s unique in and of itself. This is not a soup kitchen. It’s very good food,” Miller says.

“We’re talking about food security and undocumented people and making sure that we get elected leaders that are coming to the table with the issues for these communities as well,” Miller says.

“It’s been a strong partnership ever since. I think it’s the partnership that has made it so powerful. The resources people in the industry have have increased the presence of this platform,” adds Pourzand.

“It’s been a strong partnership ever since. I think it’s the partnership that has made it so powerful. The resources people in the industry have have increased the presence of this platform,” adds Pourzand.

So far, the partnership has served over 44,000 chef-cooked meals to Philadelphians. The meals are prepared by a rotating series of chefs in El Compadre’s kitchen and then are distributed by a network of nonprofits that The People’s Kitchen has partnered with, including Church of the Redeemer Baptist Church, Puentes de Salud, The Pennsylvania Domestic Workers Alliance, UNITE HERE Philadelphia and SEAMAAC.

A solution where it’s desperately needed

About one in five Philadelphians—more than 300,000 people—suffer from food insecurity, according to a 2018 report from Hunger Free America. The report also notes that while hunger has decreased in most parts of the country over the last few years due to reduced unemployment and wage increases, in Philly it actually increased by 22 percent between 2012 and 2017.

![]() The meals prepared by The People’s Kitchen are helping to address these issues by providing high-quality, hot meals that don’t require any preparation on the part of the recipient. Providing ready-to-eat food is an important part of addressing food insecurity because not everyone facing it has the resources or time needed to prepare food.

The meals prepared by The People’s Kitchen are helping to address these issues by providing high-quality, hot meals that don’t require any preparation on the part of the recipient. Providing ready-to-eat food is an important part of addressing food insecurity because not everyone facing it has the resources or time needed to prepare food.

Miller emphasizes that the meals are restaurant-quality, something that isn’t typically available to people who are struggling to find their next meal.

“We’re making chef-prepared, very high-quality hot meals and I think that’s unique in and of itself. This is not a soup kitchen. It’s very good food,” he says.

“[We want to] feed people good food, and make them feel happy and dignified about that,” says Miller.

The meals are made from a combination of donated food, purchased food, and ingredients grown in the urban garden, Growing Together Garden, which is owned by the Church of the Redeemer Baptist in Point Breeze. The People’s Kitchen and 215PA have been farming in the garden since this summer to help source some of the ingredients.

They’ve also received ingredients from food pantries that are trying to get rid of food that’s about to go bad. In one case, a food pantry donated a pallet of cabbage that was destined for the trash; chefs turned it into spicy pickles, that were used in meals over the next few weeks.

This isn’t merely a free meal

The People’s Kitchen is currently supported by a mix of monetary donations from the public and food donations from restaurants and other organizations. Chefs are paid for their work and though there isn’t a set schedule, Miller says that most chefs like to come in on the same day each week to prepare the meals.

![]() Chefs are also paired with culinary students from the Careers Through Culinary Arts Program (C-CAP), who help them prepare meals while learning about the food justice issues that underpin so many of the city’s restaurants. The People’s Kitchen has welcomed volunteers from high schools and colleges in the area, as well.

Chefs are also paired with culinary students from the Careers Through Culinary Arts Program (C-CAP), who help them prepare meals while learning about the food justice issues that underpin so many of the city’s restaurants. The People’s Kitchen has welcomed volunteers from high schools and colleges in the area, as well.

While addressing food insecurity is at the heart of the project, The People’s Kitchen hopes to draw attention to a range of food justice and political issues in the city. Many of the city’s restaurants are staffed by immigrant and undocumented chefs, an issue Miller and Martínez have long been vocal about.

“We need to make this about real issues, not just hand out free meals. Right from the beginning that was part of the vision,” Pourzand says.

“We need to make this about real issues, not just hand out free meals. Right from the beginning that was part of the vision,” Pourzand says.

“We’re trying to allow all the powerful things that happen in the kitchen to radiate out into our work. You have a chef, but you also have a dishwasher, maybe an undocumented worker, an owner, and a person getting a meal, and a person making a meal. And there’s all these people with maybe a different perspective,” she adds.

![]() As part of this mission, the group prepared and brought meals to a variety of Philly’s polling locations both to feed poll workers and to encourage people to get out to vote at 14 different sites across the city. On that day, they served a total of 5,650. Additionally, they brought food out to help feed activists at the Count Every Vote rallies that sprung up during election week.

As part of this mission, the group prepared and brought meals to a variety of Philly’s polling locations both to feed poll workers and to encourage people to get out to vote at 14 different sites across the city. On that day, they served a total of 5,650. Additionally, they brought food out to help feed activists at the Count Every Vote rallies that sprung up during election week.

“We can’t stop, we need to fuel the movement, we were out there at the Count Every Vote rally feeding people, and the block party feeding people,” Pourzand says. “We’ve hit a new milestone in supporting activism and community organizers through food in a way that we’ve always wanted to do, and we’re really seeing it happen.”

The work of political organizing and education about food justice issues has extended to the project’s support of culinary students in the city. Each week, the five C-CAP culinary students who are preparing meals at The People’s Kitchen participate in Zoom discussions of food-justice issues.

“It’s a great learning environment, because it’s not pressurized,” Miller says. “So they’re not just learning things in the kitchen, but about food and security, about the operation, and about digging into your own cultural roots.”

Training the next generation of Philly chefs to be mindful of food justice issues is part of The People’s Kitchen’s mission to continue growing and building awareness about food insecurity throughout the city. Miller hopes to one day be able to scale the model they’re building so that there will be People’s Kitchens serving free, chef-prepared meals to those in need across the city.

“I think the ultimate answer is that we need more People’s Kitchens across the city. We need 20 of these things in different neighborhoods,” Miller says.

The Citizen is one of 20 news organizations producing Broke in Philly, a collaborative reporting project on solutions to poverty and the city’s push towards economic justice. Follow the project on Twitter @BrokeInPhilly.