Hope is infinite. In one of his writings from shortly before his death, the Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr. advised us that “we must accept finite disappointment, but never lose infinite hope.” This is King-as-Preacher, ministering to the congregation of humanity, delivering a salve for what ailed us then and, of course, what ails us now.

These days, the disappointments feel infinite — terrorism in Israel and unspeakable death in Gaza, a tyrannical war in Ukraine, the rise and return of fascism in Europe, famine in Africa, and the withering deterioration of our environment. This list goes on — but the fact that these things will end is incontrovertible. Wars end. Fascist movements end. Famines end. And yes, even our world as we know it, at some point, will end.

How then, can we talk about hope in this moment and in this time of critical crises at home and abroad?

This is where the power of infinite hope kicks in. King’s words about finite disappointment and infinite hope compel us to take his directive as a whole. These words are a bifurcated rhetorical model, one through which we can wrestle with disappointment — accept disappointments at some point — but … and the “but” in the aforementioned King quote is doing yeoman’s work here. That acceptance is inextricably linked to an infinite reservoir of hope available to all of us.

Hope is not a commodity. It is the essence of the optimistic energy accessible to us in our times of need. Hope is at the ready to motivate us through and beyond the mundane disappointments that too often threaten to overwhelm us. We will not be overwhelmed. Our hope that things can get better — that things will be better — is embarrassing sometimes. Many people feel hopeful and don’t always (or ever) want to show it. And still others would rather center on the disappointments, ad infinitum.

“One America is beautiful … But there is another America. This other America has a daily ugliness about it that transforms the buoyancy of hope into the fatigue of despair.” — Martin Luther King Jr., in “Other America”

It is so much easier to talk about everything that’s wrong with the world than it is to do something about it. This is why the MAGA mentality is so compelling to a certain segment of the American electorate. The acronym — Make America Great Again — represents a statement of faux hope that America might return to a mythological greatness that Dr. King dedicated his life to deconstructing. The MAGA slogan represents those who truck almost exclusively in grievance culture, a hopeless political enterprise designed to feed off of pain, anger and racial resentment. The truth is that America wasn’t ever that great for a whole lot of Americans through much of the 18th, 19th, and 20th centuries.

Another America

In Dr. King’s “Other America” speech he said, “[t]here are two Americas. One America is beautiful … But there is another America. This other America has a daily ugliness about it that transforms the buoyancy of hope into the fatigue of despair. In this other America, thousands and thousands of people … walk the streets in search for jobs that do not exist. In this other America, millions of people are forced to live in vermin-filled, distressing housing conditions …”

This is King-as-Professor. But like a preacher, he makes it plain: “The most critical problem in the other America is the economic problem.” This is true even today. As of late last year, 66.6 percent of the total wealth in America was owned and controlled by 10 percent of the richest families and corporations in this country. (I am not making up that 66.6 number for any kind of ominous or demonic effect.)

In “A Proper Sense of Priorities,” a speech that King delivered less than two months before he was assassinated, his critical assessment of America was on full display. “Our involvement in this cruel senseless unjust war [in Vietnam] is a tragic expression of the spiritual lag of America. And this is why we must be concerned about it on a continuing basis. I need not go into a long discussion about the war and its damaging effects. We all know,” he said to an audience of thousands in 1968. This is King-as-Prophet.

“We live in a nation that is the greatest purveyor of violence in the world today. And any nation that spends almost $80 billion of its annual budget for defense channeled through the Pentagon and hands out a pittance here and there for social uplift is moving towards its own spiritual doom …. We’ve played havoc with the destiny of the world … Somewhere we must make it clear that we are concerned about the survival of the world …”

King-as-Prophet is probably the King we will continue to hear less and less of, but we should not confuse this deliberate cover-up with the enduring truth of Dr. King’s critique of this nation. Late last year, President Joe Biden signed the National Defense Authorization Act into law. This act allocates $816.7 billion for the defense budget. The US defense budget is just over 3 percent of gross domestic product (GDP), signaling its prioritization in policy and politics. The United States spends more on defense than any other nation in the world. Meanwhile, 12 percent of our fellow Americans live in poverty; we boast the largest prison population in the world; have the highest infant and maternal mortality rate among developed countries — especially among Black Americans; and one in five children here go hungry.

The criticisms of America brought by King-as-Prophet continue to ring true. Our priorities are hopelessly out of alignment with our humanity.

Yes, he had a dream

Most people will likely associate Rev. King’s sense of hope with his most widely-quoted (and truncated/edited) “I Have a Dream” speech. No need to quote snippets here, you will all be hearing these sanitized missives in ads, commercials, and on cable news for the next week or so. Far fewer will reference King’s much less popular “Unfulfilled Hopes” speech, a sermon that predates King’s hopeful “I Have a Dream” message by nearly a decade. King delivered “Unfulfilled Hopes” in April of 1959 at the Dexter Avenue Baptist Church in Montgomery, Alabama.

In “Unfulfilled Hopes” King says,“We discover in our lives, soon or later, that all pain is never relieved. We discover, soon or later, that all hopes are never realized. We come to the point of seeing that no matter how long we pray for them sometimes, and no matter how long we cry out for a solution to our problems, no matter how much we desire it, we don’t get the answer.”

“I have one thing left. Life has beaten it down; it has broken away from me many things, sometimes my physical body. But at least it has left me with a will, and I will assert this, and I refuse to be stopped.” — Martin Luther King Jr., in “Unfulfilled Hopes”

This is King-as-Preacher, again. He connects with the congregation of humanity through a transparent analysis of our “shattered dreams.” But he won’t allow the hopelessness of his message to outstrip the power of hope itself. Later in the sermon, Minister King points to the concept of the “dynamic will,” a concept he borrows from Deep River, by the great and influential theologian Howard Thurman. In his sermon, King defines the dynamic will as existing in “the individual who stands up in his circumstances and stands up amid the problem, faces the fact that his hopes are unfulfilled.

And then he says, “I have one thing left. Life has beaten it down; it has broken away from me many things, sometimes my physical body. But at least it has left me with a will, and I will assert this, and I refuse to be stopped.”

The vast valley of difference between “I Have a Dream” and “Unfulfilled Hopes/Shattered Dreams” is a critical chasm across which we are all called to continuously revisit Dr. King’s rhetorical mastery and the many ways that his thinking about this world (and the next) evolves through his work and evidences itself in his words over time. The power of this critical exegesis of King’s work is that it directly confronts the naivete of any sanitized versions of King’s legacy in perpetuity. King’s vision for infinite hope was not naïve; it was cultivated in the cauldron of conflicting conceptualizations of hope — hope unfulfilled and hope infinite.

Understanding King in these complicated ways should give all of us hope. His is a limitless legacy of hope bestowed upon us in ways that challenge us to embody all of its infinite potential. But —and here I hope my “but” can do the work of King’s “but” – hope in both its infinite and unfulfilled meanings, ultimately requires us to act.

![]()

MORE FOR MARTIN LUTHER KING DAY FROM THE CITIZEN

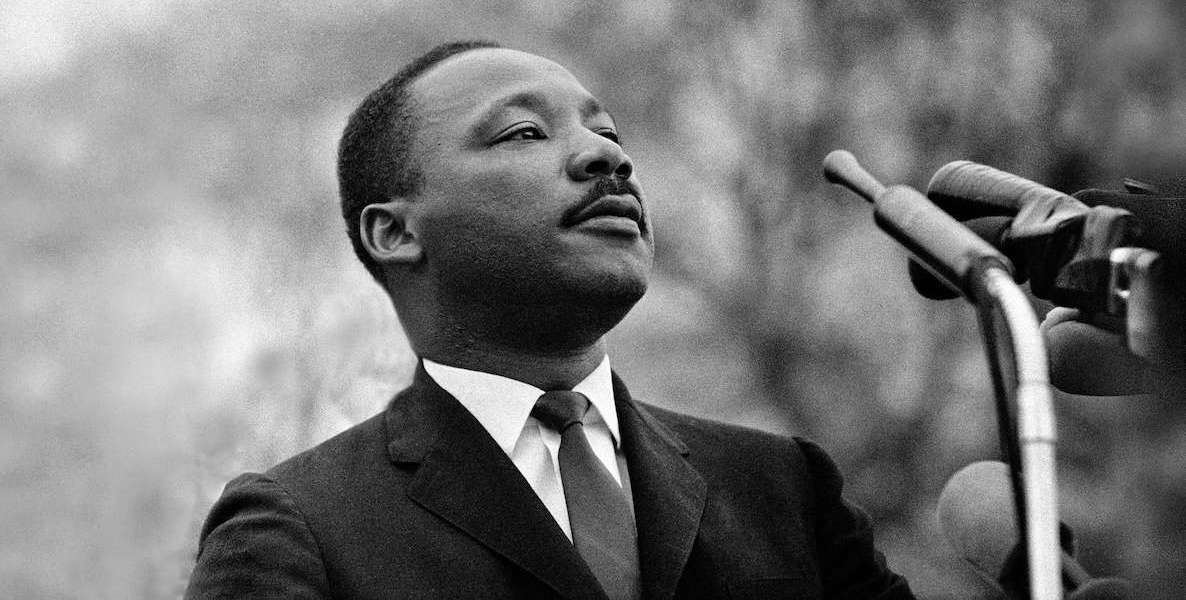

Photo by Stephen F. Somerstein-Somerstein in 1965.