Every Wednesday, the smartest, if not the best, coach in Philadelphia is not to be found at the Eagles’ NovaCare facility, running gridiron behemoths through versions of the Philly Special. No, he’s at Gryphon Cafe in Wayne, and he’s a slight, unassuming ball of energy named Roy Rosin, who, each week, schedules his caffeinated Wednesdays in hour increments, so that an array of local startup entrepreneurs, disruptors, clinicians and thought leaders can take turns sitting before him, airing their trouble du jour, seeking his wisdom.

Rosin, 50, toils by day at Penn Medicine, where he’s been chief innovation officer since 2012. At Penn, he’s been instrumental in introducing a culture of self-inquiry and experimentation; Citizen writer and co-founder Ajay Raju has dubbed our region “Cellicon Valley” owing to the new thinking and measurable outcomes being derived by Rosin and his co-conspirators at Penn Medicine.

Tellingly, the young disruptors seeking Rosin’s input on their business plans over lattes on Lancaster Avenue are in search of the same thing he brings to Penn the rest of the week: A focus on relentless self-interrogation, a process by which all suppositions are held up to inquiry. When contemplating a new idea, rather than ask “why,” Rosin asks, in effect, “so what” over and over again. He calls this process “the five so-whats,” and he’ll start a steady stream of such inquiries (“What would be good about that?” is another, less in-your-face, way to ask it) until the real challenge and mission reveal themselves.

Rosin likes to warn that innovation is often confused with creativity, when it’s really more earthbound than it is mysterious. The secret, he says—and if there’s an overriding Rosin postulate, this is likely it—is to fall in love with the problem, not the solution.

“You have to do something to learn something,” Rosin says, in full-on apostle mode. “You have to stimulate the environment to see if that change gets what you want. You can’t do stuff in a conference room or on a whiteboard. You have to go out and do it. You don’t begin by asking if your idea works or not—that’s the old way. The first thing you ask is, ‘How can it work? Can I get it to work? Can I change it, morph it, evolve it, shape it, reshape it, reimagine it to get it to work?’ Remember, Youtube started as a video dating service, Facebook was, like, a hot or not site, and Android was for cameras, not phones.”

This intellectually existential way of looking at things—it’s all a journey, without regard to outcome—comes straight out of Rosin’s background. If he’s the smartest innovator Philly hasn’t heard of, there’s a certain symmetry to that, because he was mentored by the little known disrupter who—and this isn’t hyperbole—arguably created Silicon Valley. Bill Campbell had a losing record as the Columbia University football coach in the 1970s, but he went on to reinvent himself as the guru of Palo Alto.

Rosin likes to warn that innovation is often confused with creativity, when it’s really more earthbound than it is mysterious. The secret, he says—and if there’s an overriding Rosin postulate, this is likely it—is to fall in love with the problem, not the solution.

By all accounts, Campbell, who died in 2016 at 75, was profane, hard-charging, and unafraid to lead. Over beers at the Old Pro, the sports bar he co-owned, and on long walks, Campbell would mentor Steve Jobs, Google’s Larry Page and Eric Schmidt, Jeff Bezos, Sheryl Sandberg and pretty much every other titan of the tech economy. They called him “Coach” and genuflected before him; virtually every success story in Silicon Valley owed something to him.

Campbell, known as the “CEO Whisperer,” shunned press coverage, despite chairing Apple’s board, despite serving as CEO of Intuit and, later, as its Chairman. Back in the nineties, Campbell hired Rosin, a Stanford MBA, at Intuit, where Rosin rose to head innovation.

Rosin spent 18 years at Intuit, where he developed an internal incubator designed to rapidly turn ideas into actions, and actions into outcomes. That involved immersive research—he and his team would move in with customers to experience firsthand the role their software played in real time in real homes—and developing ways to quickly validate or invalidate hypotheses, like setting up “fake back ends”—testing ideas before investing in complex systems. It was a nimble, inventive, fail fast culture, created by Intuit founder Scott Cook in 1983 and driven by Campbell.

“Despite the fact that he was insanely brilliant, Bill had enough humility to say, ‘I think you know more than I know, so tell me the story, tell me how you’re thinking about it,’” Rosin recalls. “And then—Bill would never say this—it was almost the Socratic method. He’d check for logic, check for framework, check for whether you were making the right tradeoffs.”

From Campbell, Rosin learned that innovation wasn’t just about the technology. It was much more about getting the right people on the team, establishing a clear and energizing purpose, and about paying attention to the human details behind the work. He saw in this old-school coach—Campbell would slap male and female underlings on the butt, as though they were breaking from a huddle on the football field—the power of just the right mix of decisiveness with emotional intelligence.

Once, Rosin went to Campbell with a problem. An employee who brought in some $20 million in revenue had become a divisive office presence.

“Fire him,” Campbell barked.

“Bill, he drives $20 million in revenue,” Rosin replied.

“The cohesiveness of the team is worth more than that,” the Coach said. “Do the right thing, not the easy thing.”

Another time, Rosin had two employees who didn’t get along, and it was impeding the work. Campbell’s cure? A seating chart. “Make them sit together,” he said. “How people interact and what atoms bounce off each other in the office really matters. They’ll see the other isn’t some draconian vampire. They’ll see that each of their stories are real stories.”

Thinking of it now, Rosin shakes his head. “Bill was just always good at getting to that kernel of humanity,” he says. “Which made him somebody you wanted to work for.”

When contemplating a new idea, rather than ask “why,” Rosin asks, in effect, “so what” over and over again. He calls this process “the five so-whats,” and he’ll start a steady stream of such inquiries until the real challenge and mission reveal themselves.

And which made the work ever-stimulating. Campbell’s penchant for seeing problems from just a slightly different perspective, and Intuit’s full-throated embrace of iteration and reiteration, is what Rosin evangelizes for at Penn and with startup founders like Lia Diagnostics, which markets the first flushable pregnancy test, or Towerview Health, which bills itself as a “personal assistant for your medications.”

Rosin is trying to get his charges to do what Campbell once implored of him: Be open to redefining your problem. Rosin is full of countless examples of this process, and they come in breathless anecdotes. There is, for example, the decades old case study of Hertz Rent-a-Car that Rosin often uses as an object lesson. The problem only seemed to be that the line to rent a car was interminable.

“If you did normal operations improvement, you’d define the problem based on what you observe: The line is moving too slow,” Rosin says. “That leads you to ask, ‘Why is the line so slow’ and you’ll arrive at fixes like, ‘Maybe I should innovate on my staffing model or the paperwork customers have to fill out.’ Those things are fine, but they’re incremental. Because just asking why leads you to improve the existing thing—you have an overly prescriptive solution baked into your problem statement. But if you ask ‘So what?’ Someone says, ‘The line is too slow.’ You say, ‘So what?’ They look at you kind of funny. And then, if you keep asking, they may say something like, ‘It’s too slow, and I want to be on my way.’ Ah. Okay. So it’s not really about the speed of the line, it’s about minimizing the time from getting off the plane to being in your car? Well, that’s different. Now I can invent Hertz Gold—a new answer that goes beyond just improving the existing thing. It was like EZ Pass—you do things ahead of time when you’re not in a rush.”

![]() In fact, on Rosin’s first day at Penn, he unveiled his So What strategy. Penn was considering adopting an Open Table-like scheduling system. “I love Open Table,” he says. But, on that day, his questioning sought to unearth the story behind the proposal.

In fact, on Rosin’s first day at Penn, he unveiled his So What strategy. Penn was considering adopting an Open Table-like scheduling system. “I love Open Table,” he says. But, on that day, his questioning sought to unearth the story behind the proposal.

Over and over, he heard that, again, the problem was the time it took for a new patient to get an appointment. Dermatology? Two months. Neurology? Three. “So it became clear that online scheduling would just make it easier to see how long it takes to get an appointment,” he says. “Online scheduling didn’t address the problem. In fact, it would just heighten the patient’s frustration. The problem was access, not scheduling.”

Rosin didn’t have the answer, but his team dove in and came up with what is called a “load balancing intervention.” Turns out, there were Penn medical practices in Center City that could see patients the next day, but they hadn’t been part of the institution’s full menu of options open to all patients, in part owing to what Rosin refers to as the “challengeable assumption” that a patient in West Philly wouldn’t travel a mile to see a doctor. “What happened is, patients did make the trip, and some practices and patients were helped,” he says.

“We’re trying to make the right choice the easy choice,” Rosin says. “This is my new obsession, the idea that no action, or less effort, produces the right result.”

Or take a more recent case study: The story of the aforementioned TowerView Health, the “personal assistant for your medications.” A Penn and Blue Cross study revealed that patients only take their medications 50 percent of the time. Yet TowerView nearly doubles that.

Rosin estimates that medication non-adherence is linked to roughly $300 billion worth of health care costs. “It’s the first time I’ve heard of a company get to close to 100 percent medication adherence,” Rosin says of TowerView’s early success, another example of seeing the problem you’re trying to solve for in new light.

“A lot of medication adherence issues are not what you’d think,” Rosin says. “You’d think the issue was one of people forgetting to take their meds, but the real issue can be forgetting whether they took their meds. That calls for a totally different solution. Sometimes meds aren’t taken because, you know, ‘I don’t want to think of myself as sick.’ Or ‘It doesn’t fit into my life the way I want.’ Or ‘I didn’t have time to pick up my refill at the pharmacy.’”

TowerView patients, then, get a package from their pharmacy with their meds presorted into manageable vials equipped with sensors that record when and if the medicine is taken. If not taken, reminders are sent or texts are sent to loved ones. The critical point, Rosin emphasizes, is that the solution comes last. Figuring out the problem is first.

Rosin is an idea enthusiast, someone who comes alive openly plotting about turning thought into reality. The words come tumbling out, one on top of the other, as though, if he could only get the point across sooner, the sooner this new intervention or program or protocol might help real people. Health care is a maddeningly complex field; has there ever been an industry more in need of the type of inspired customer service interventions Rosin once delivered to users of, say, Intuit’s Quicken? Today, Rosin turns most fiery when talking about the work he’s doing in partnership with Mitesh Patel’s Nudge Unit at Penn, which employs “choice architecture” to nudge patients toward healthy behaviors with minimal or no effort on their part.

Rosin points out that, in 2006, Nobel Prize winner Richard Thaler’s research convinced lawmakers to encourage companies to auto-enroll employees in retirement savings plans. Savings took off, because opting out was the option that required action.

“We’re trying to make the right choice the easy choice,” Rosin says. “This is my new obsession, the idea that no action, or less effort, produces the right result. People look at me kind of funny when I talk about this. But I’m like, okay, what happened in Grand Rapids, Michigan in 1945? It was the first time we ever fluoridated water. There was a massive drop in tooth decay, but the people of Grand Rapids didn’t do anything differently. Or think about Sonic, the burger chain today. They’ve replaced 25 percent of their beef with chopped mushrooms. You went from 600 calories to 350 with no change in your behavior.”

Rosin is an idea enthusiast, someone who comes alive openly plotting about turning thought into reality. The words come tumbling out, one on top of the other, as though, if he could only get the point across sooner, the sooner this new intervention or program or protocol might help real people.

In healthcare, the applications for this type of thinking are endless. “One of the first nudges Mitesh’s team led involved the prescribing system in the electronic medical record,” Rosin explains. “Like earlier research in organ donation showed, If you want organ donation to be more actively chosen, you make being a donor the default. If you do nothing, you’re a donor. If you don’t want to be a donor, you have to opt out. That’s what we did with generic prescriptions. Mitesh and his team made the generic option the default, and the use of generic drugs went to 99 percent, saving both patients and the system money.”

![]() Rosin lives in St. David’s with his wife, Dr. Rachel Ebby-Rosin, a researcher on the Academic Innovations team at Penn’s Graduate School of Education, and their three kids—a 7th, 9th and 11th grader, respectively. How odd it must be for them, I wonder, for dad to be this dynamic, problem-solver of a thinker…at the precise moment when whatever dad does elicits eye rolls.

Rosin lives in St. David’s with his wife, Dr. Rachel Ebby-Rosin, a researcher on the Academic Innovations team at Penn’s Graduate School of Education, and their three kids—a 7th, 9th and 11th grader, respectively. How odd it must be for them, I wonder, for dad to be this dynamic, problem-solver of a thinker…at the precise moment when whatever dad does elicits eye rolls.

He laughs. “My kids will tell you I am terrible at this at home,” Rosin says. “Like, most parents resort to yelling, as if the problem they’re solving for is that the kids didn’t hear them the first time.”

So what would Roy Rosin, innovation coach, tell Roy Rosin, parent? He smiles. “If you really used this methodology at home, you’d learn that the problem isn’t that they didn’t hear you,” he says. “Maybe they don’t want to hear what you’re saying. So be more creative.”

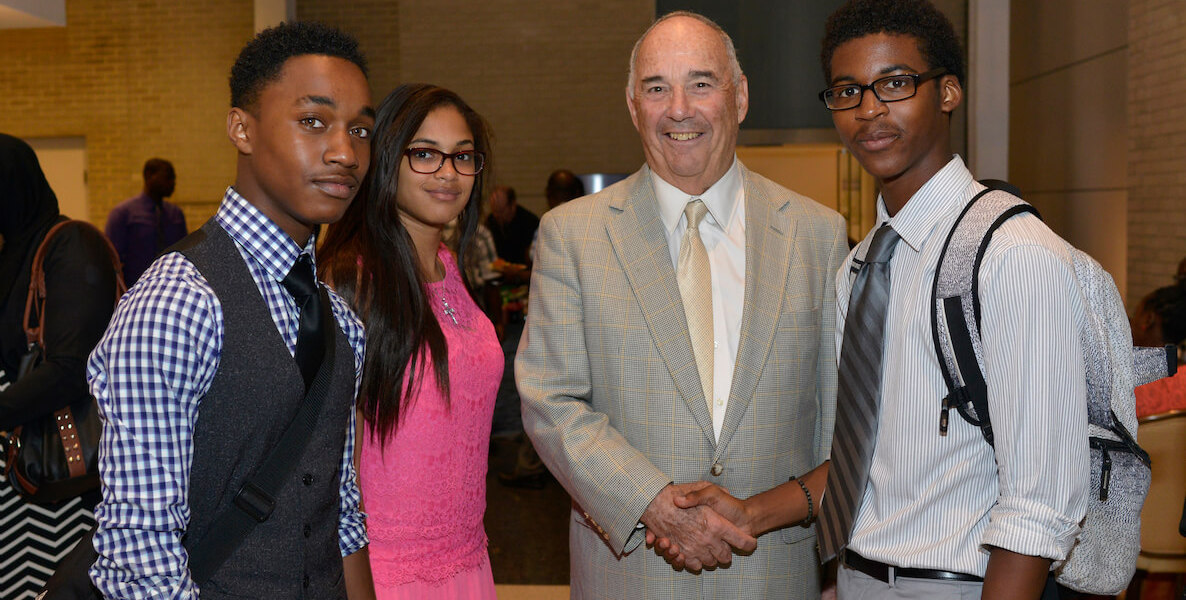

Photo via catalyst.nejm.org video