Let’s posit from the start what ought to be self-evident: There is no liberal or conservative way to defeat a deadly virus. Yet, if you’re loyal to the values of the Enlightenment—if reason and science and evidence light your way—then you ought to be very concerned about our age of alternative facts and dueling amen corners. And you ought to find it very difficult to be a Phillies fan right now.

If you haven’t heard, something like half of our baseball team is unvaccinated. Major League Baseball is willing to relax its Covid-19 safety protocols for those teams—defined as players and staff that travel with them—that are 85 percent vaccinated. The Phillies are nowhere near that number, and numerous players have already missed multiple games as a result.

Some, like pitcher Aaron Nola, proclaim the matter to be a “personal choice”; others do an almost too believable job of projecting ignorance: “I don’t know, I haven’t talked to the guys,” relief pitcher Hector Neris said. “It’s like, different opinions. Everybody is different.”

MORE ON VACCINE EFFORTS IN PHILADELPHIA

That’s the thing, though. This isn’t a matter of opinion. The facts are overwhelming; we’re in a pandemic of the unvaccinated. Not to hear our Phils tell it, though. It’s one thing for twentysomething ballplayers to make uninformed public pronouncements. But it is hugely disappointing to hear their adult manager do the same.

“I think it’s a personal decision that I will not get involved in because it’s a personal decision,” Girardi rather redundantly told the press when asked why he just doesn’t mandate that his players take the same vaccine he’s taken. “So whatever the player decides, I will back him no matter what.”

There are a number of ways to call out Girardi’s lack of moral leadership here. But let’s stick to the big picture. What’s so alarming about Girardi’s casual Swiss-like neutrality is that, because he’s an authority figure, it can fuel what is already so rampant in American culture: A doubling down on know-nothingism, and a war on the very notion of expertise.

In 2017’s The Death of Expertise: The Campaign Against Established Knowledge and Why It Matters, author Tom Nichols might just as well have been anticipating Girardi: “Americans have reached a point where ignorance, especially of anything related to public policy, is an actual virtue,” Nichols writes. “To reject the advice of experts…is a new Declaration of Independence: No longer do we hold these truths to be self-evident, we hold all truths to be self-evident, even the ones that aren’t true. All things are knowable and every opinion on any subject is as good as any other.”

If civil society is no more than just a matter of “personal choice” rather than a thoughtful balancing of rights and responsibilities, then the perils of Girardi’s relativism are plain to see. It’s every man for himself. We’re no longer a community. We’re no longer a team. Quite an odd thing for a team manager to represent.

What’s so alarming about Girardi’s casual Swiss-like neutrality is that, because he’s an authority figure, it can fuel what is already so rampant in American culture: A doubling down on know-nothingism, and a war on the very notion of expertise.

It wasn’t always like this, folks. Seventy years ago, the spread of polio was creating widespread panic, particularly in the summer months. Public swimming pools were shuttered. Sitting in a movie theater was subject to extreme social distancing. Insurance companies sold polio insurance for newborns. Hospitals set up special units with “iron lungs” —metal coffin-like contraption that aided respiration.

Early attempts to discover a vaccine resulted in multiple deaths of children. Still, society was united in its quest to defeat a common foe. No one screamed “fake news” or accused President Truman of merely seeking votes when he called the nation to shared purpose: “The fight against infantile paralysis cannot be a local war,” Truman said in a speech broadcast from the White House. “It must be nationwide. It must be total war in every city, town and village throughout the land. For only with a united front can we ever hope to win any war.”

By 1957, a nationwide inoculation program was underway. In twenty years, polio would be virtually wiped out. That was a testament to the two strains of our national character that Alexis de Tocqueville had observed: the practicality and rationality of the American citizen.

Later, I was living in New York when it became the first state in the nation to mandate the wearing of seat belts in cars. It was the eighties, so folks were busy wearing parachute pants and listening to their Sony Walkmans. There was no time for outrage. Oh, people were annoyed—there were news reports of individuals tearing seat belts out of their new cars—but there were no organizations formed, no rallies, and no death threats made against Governor Mario Cuomo, Andrew’s non-sexually harassing father.

Less than 15 percent of America was buckling up when Cuomo’s law first passed; now, over 90 percent of the nation does, and it saves roughly 15,000 lives a year. And guess what? Like wearing a mask or getting a couple of shots in the arm, fastening a seat belt is not that inconvenient, as any well-practiced flight attendant is happy to demonstrate for you.

If Girardi can’t see how getting vaccinated is something every citizen owes every other citizen, it makes me wonder if he really does understand what it means to be part of a team, after all.

Point is, at various times in our past, our neighbors had the humility to admit they didn’t know what they didn’t know, and so they sought out the facts and changed their behavior accordingly. But we live in the Internet Age, which has provided more noise and less clarity than at any point in our history. It’s easier now than ever to access your own confirmation bias. Just search Google and you’re bound to find something that tells you that what you felt all along was damn right, after all.

The reason Girardi’s comments bothered me so was that I’ve come to realize that, the older I get, the more baseball means to me. It’s a game that is all about failure; the best players succeed at the plate only 30 percent of the time. Over the long course of a season, the teams that win are those that steadily apply principled, selfless acts. The batter who “sacrifices” himself by bunting his teammate to second base. The hitter who “hits behind the runner” to advance a player without regard to his own fate. The catcher who backs up his infielders on routine foul ball pop ups.

These are actually acts of community; the game really does provide a prescription for how to live. Girardi no doubt preaches the wisdom of selflessness on the field to his clubhouse. But if he can’t see how getting vaccinated is something every citizen owes every other citizen, it makes me wonder if he really does understand what it means to be part of a team after all.

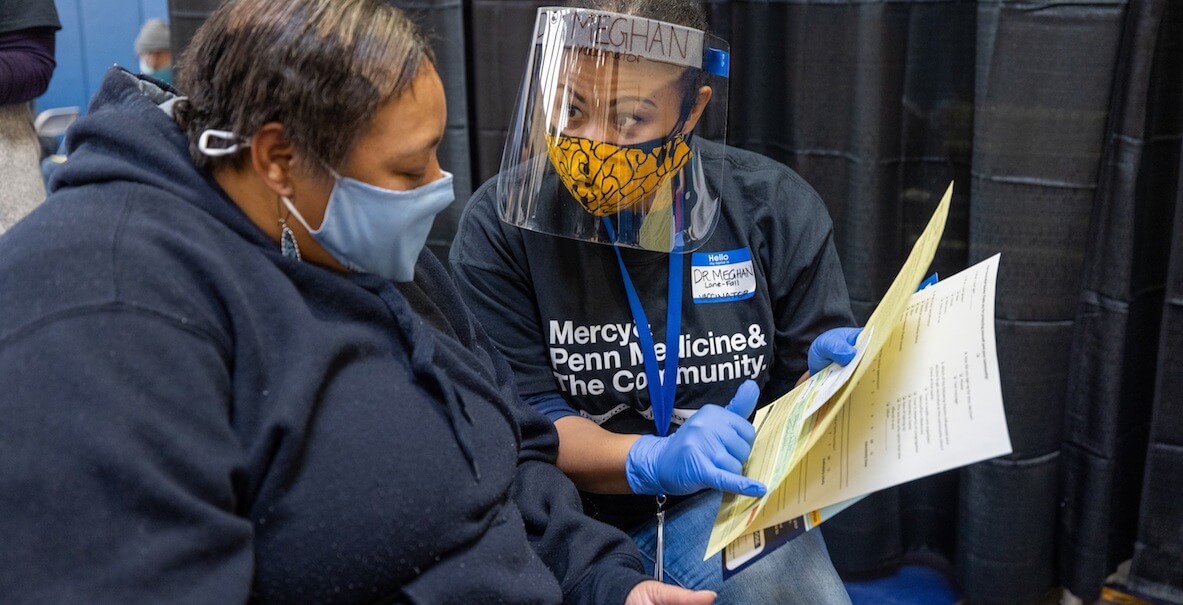

Header photo by Miles Kennedy for the Phillies