to this story in CitizenCastListen

Arguments over who and how much to tax, or whether to spend on armaments over food stamps, are essentially moral in nature. You can tell a lot about the beliefs of a society by its political budgets.

But that’s not all that our public budgets connote. As budget guru Allen Schick has pointed out, budgets are also a type of strategic roadmap; they say, in effect, by spending money thusly, we will arrive at a shared vision. They are the link between goal and mission accomplished.

That requires having a vision in the first place, of course. Which brings us to Philadelphia, where, compared to peer cities, we appear to be lagging behind on both vision and budget.

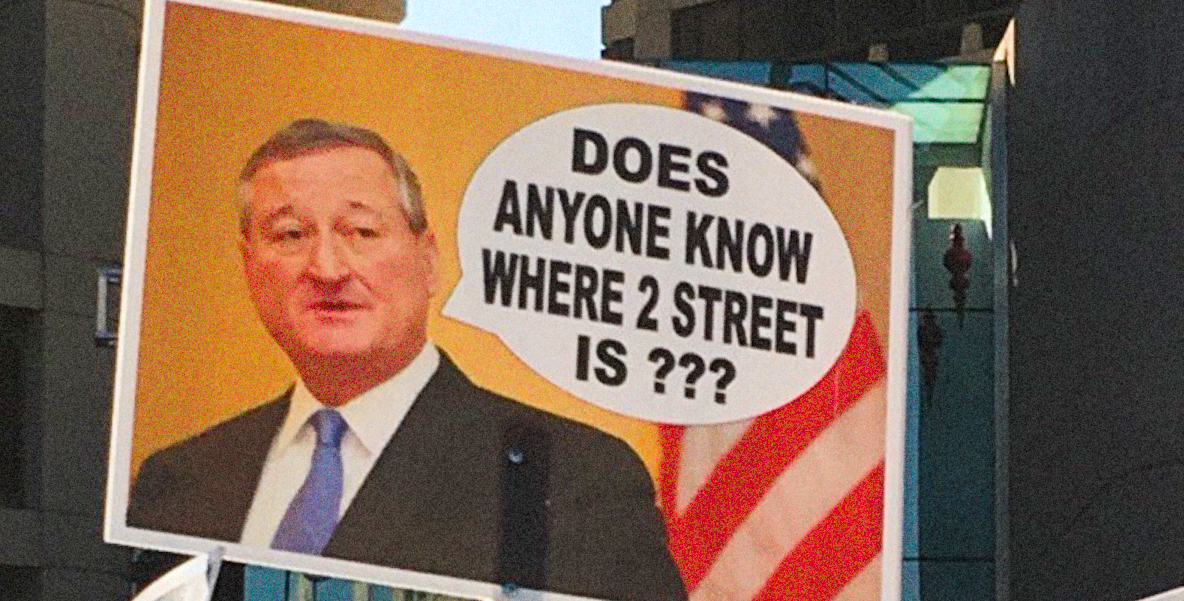

A week ago, Mayor Jim Kenney proposed a revised budget in light of the Covid-19 crisis, and if we’ve learned anything it’s that, rather than rising to the moment, our mayor has shrunk before it.

In other cities—from Chicago to San Francisco, from Houston to D.C.—citizens are freaking out about their future, just like here. But in those cities, those who are worrying can at least take some comfort in the fact that a cross-section of their leadership class is on the case…and has a plan.

Let’s recap. Amid plummeting tax revenue due to the economic shutdown and soaring medical costs, the mayor and his director of finance, Rob Dubow, sequestered themselves to redo their record $5.2 billion budget. Even though, counterintuitively, they’d just given unionized city workers a raise, they promised significant pain and adverse effects on city services.

Read the brief version of this storyShort On Time?

They were not alone. Other cities find themselves in similarly dire circumstances and many have already made hard choices. In Detroit, Mayor Mike Duggan announced the layoffs of seasonal employees and cut the pay and hours of 2,200 full-time city workers, and cut programs like Parks and Rec en route to enacting a 16 percent budget cut—compared to Philly’s 11 percent. In Cincinnati, 1,700 city workers were furloughed. Miami and San Antonio went with a furlough/layoff combo. In Dayton, Ohio, Mayor Nan Whaley furloughed a quarter of her workforce.

Guess what none of these mayors did? Raise taxes. Because, when facing a near-Depression, when the long term goal is to stimulate growth, and when a citizenry is already strapped, longstanding economic tenets hold that any attempts to tax your way back into prosperity are likely to be regressive, by definition.

But Kenney zigged where other mayors have zagged. While he has promised layoffs “in the hundreds” of both union and non-unionized workers in a city with roughly 25,000 employees, he has presented a revamped budget that protects much of the discretionary spending he’s added over the course of his mayoralty, sparing programs like Pre-K and community schools while axing the funding of arts and culture programs.

At the same time, Kenney proposes raising in excess of $50 million in new taxes, which doesn’t even include a $68 million property tax hike in order to help fund the school district. (To fully understand the mayor’s budget proposal, City Controller Rebecca Rhynhart has released a cool interactive tool that lays it all out, and that begs the question: Why isn’t the administration as transparent about its own proposal as the Controller’s Office?)

While, in normal times, the mayor’s proposal would qualify as a “balanced approach,” as his chief of staff described it, these times are anything but normal. We’re facing economic upheaval like we haven’t seen in 90 years.

The real question ought to be: Does the mayor’s budget offer a blueprint that smartly positions Philadelphia for a speedy recovery when the world comes back?

Let’s give the mayor a mulligan and urge him to humbly concede that he doesn’t have all the answers, but will empower those who do. Or, better yet, let’s recruit a band of local patriots to step up, do a deep dive, and author and enact a true recovery plan for Philadelphia.

That would be a hard no. You can almost hear the cynical and lazy thinking behind what feels like a hastily thrown-together budget: Let’s raise the parking tax yet again—no one likes parking magnates! Or: Let’s raise the wage tax on suburbanites—they don’t vote here!

It would be asinine to raise taxes right now on airlines, restaurants and hotels, right? That’s why a sizable portion of the CARES Act is going to prop up those industries, to give them a chance to survive and recover. Not because we love airlines, but because we love jobs.

Plan a better budgetDo Something

Remember, budgets are more than P&L statements; they’re also strategic roadmaps. But, as I outlined a couple of weeks ago, visionary thinking has never been the calling card of our mayor. Let’s consider who likely weighed in on his underwhelming budget proposal: In addition to Kenney and Dubow, there’s Managing Director Brian Abernathy, Chief of Staff Jim Engler, and Deputy Mayor of Labor Rich Lazor.

All are competent, committed public servants, even if, as a group, their whiteness and maleness is striking when it comes to the kitchen cabinet of a supposed progressive. But what really jumps out is their lack of diversity of experience; none have private sector chops, nor have any run any large organization otherwise.

Those in the mayor’s ear don’t have CVs steeped in innovation and data-informed experimentation. It feels pretty passe, doesn’t it, this idea of city officials all gathering in a room and only talking to one another before, in their hubris, emerging with what they see as the answer?

That’s why so many mayors elsewhere have done just the opposite. They’ve convened the best and the brightest within their communities to collaborate with elected officials on smart, data-driven strategies.

It’s a new way to think about governing: As the product of cross-sector collaboration—more of a network than a government, with its turf wars, bureaucracy and tendency toward top-down dictates. And it also makes for smart politics, because in the practice of what Bruce Katz and the late, great Jeremy Nowak called “horizontal leadership” in their book The New Localism, lies constituency-building.

In announcing her group of bold-face names, Bowser said, in effect, that this was a once-in-a-generation opportunity to not just reopen a city, but to build a more equitable one.

So let’s go on a travelogue of some case studies that stand in stark contrast to Jim Kenney’s old-school approach, shall we?

First, a visit to my mayoral crush, Chicago’s Lori Lightfoot. Last month, she convened a Covid-19 Recovery Taskforce to advise city government on its economic recovery plans. It’s co-chaired by Lightfoot and former White House Chief of Staff Sam Skinner and includes experts from private industry, governmental leaders, policymakers and community-based partners. Critically, the taskforce is not staffed by government workers; it’s staffed by Chicago’s Civic Consulting Alliance, which dispatches nonprofit and business leaders to work with local government, infusing the bureaucracy with visionary planning and policy implementation experience.

In other words, Lightfoot hasn’t staffed the task force with her political apparatchiks, but she has set herself up to benefit politically. Now, unlike Kenney, her plan for recovery isn’t just her own. It has the force of a public/private partnership, powered by civic leadership, behind it.

Out in San Francisco, Mayor London Breed and Board of Supervisors President Norman Yee created their own Covid-19 Economic Recovery Task Force. It includes the CEO of the Chamber of Commerce and the Executive Director of the San Francisco Labor Council, and its mission is to focus like a laser beam on three recovery policy areas: Jobs and business support; vulnerable populations; and economic development.

In Houston, Mayor Sylvester Turner appointed Marvin Odum to the position of “Recovery Czar” and gave the former Shell Oil CEO wide latitude to come up with solutions and strategies to get Houston’s economy moving again. Odum has an impressive track record, having overseen the city’s recovery after Hurricane Harvey. He’ll be working in tandem with State Rep. Armando Walle, who is heading the recovery for Harris County; together, they’re shepherding through plans for relief for small business owners and workers, and focusing on reinvigorating underserved areas.

Finally, Washington, D.C. Mayor Muriel Bowser formed the Reopen DC Advisory Group, chaired by Ambassador Susan Rice and Michael Chertoff, former About our mayorRead More

In announcing her group of bold-face names, Bowser said, in effect, that this was a once-in-a-generation opportunity to not just reopen a city, but to build a more equitable one. It was an embrace of the “never let a good crisis go to waste” mantra of Rahm Emanuel during the last great economic crisis.

And that brings us back to Mayor Jim Kenney. By treating this moment as just another P & L challenge—let’s cut some from here, let’s raise that amount there—we’re in danger of missing an opportunity. The times call for more than just math.

The real question ought to be: Does the mayor’s budget offer a blueprint that smartly positions Philadelphia for a speedy recovery when the world comes back? That would be a hard no.

City Council has yet to weigh in on Kenney’s proposal, but what are the chances that it brings the level of seriousness and vision the times demand? Our august legislative body suffers from the same maladies as the administration: The curse of incrementalism, valuing the political over the reformative, an allergy to collaboration.

Case in point: When Council unveiled its ludicrous anti-poverty plan a couple months ago, (ludicrous in its goal of reducing poverty by 33 percent in 5 years, when the nation cheered New York’s eye-opening 4 percent reduction), the head of a related prominent nonprofit told me they were called by Council President Clarke’s office that morning and asked to attend the press conference, having never weighed in or seen the plan. If our last, best hope for a smart recovery is the vision of Darrell Clarke, we’re screwed.

But maybe it’s not too late. Let’s give the mayor a mulligan and urge him to humbly concede that he doesn’t have all the answers, but will empower those who do. Or, better yet, let’s not wait for the mayor to see the light. Let’s recruit a band of local patriots to step up, do a deep dive, and author and enact a true recovery plan for Philadelphia.

I wrote this two weeks ago, and it’s more apropos now than then:

How cool would it be if, rather than Jim Kenney and Rob Dubow emerging this week with a budget of severe cuts, they strode onto the scene armed with a document informed by a diverse roster of local all-stars—everyone from private sector titans like Comcast’s Brian Roberts and Merck’s Ken Frazier to nonprofit visionaries like CHOP’s Madeline Bell to activists like Mural Arts’ Jane Golden and maybe some emerging leaders we haven’t even heard of yet—that laid out a shared vision for how we can all advance, together?

In other cities—from Chicago to San Francisco, from Houston to D.C.—citizens are freaking out about their future, just like here. But in those cities, those who are worrying can at least take some comfort in the fact that a cross-section of their leadership class is on the case…and has a plan.

Photo illustration by Dan Shepelavy