Megan Garner’s first acts as sustainability manager for the School District of Philadelphia were to help the district update buildings to be more energy efficient, including shifts to compostable lunch trays. These changes, while important, were about operation — not preparation.

Garner knew sustainability needed to be taught, as well. After all, the District’s 120,000-some students were already living in a world shaped by global climate change. Some live in heat islands, where a lack of green infrastructure makes temperatures up to 20 degrees hotter than the rest of the city. Others struggled with wildfire smoke this summer, and watched a family swept away by a flash flood in Bucks County. Shouldn’t our kids learn how to live more sustainable lives?

“As an educational institution, we had a responsibility to connect what we were doing on the operations side to the curriculum side,” Garner says.

Across the Delaware, interdisciplinary climate change education is already making an impact.

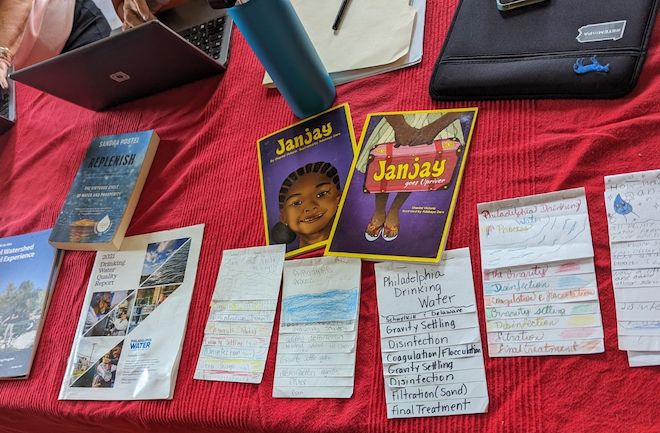

Today Garner oversees GreenFutures, a professional development program available to SDP educators who opt in. The interdisciplinary curriculum centers around our urban watershed, combining historical environmental education with science and math, teaching students about stormwater and climate change’s impact on their neighborhoods.

And yet … only 337 out of 7,000 SDP teachers have received the training. Even now that Pennsylvania has updated its statewide science standards to include environmental literacy and sustainability across all grade levels, most Philly students will never learn how climate change is impacting them specifically — and how they can make a difference.

Philly — and PA — could look to New Jersey for an example of how to make climate education widespread. Last year, the Garden State became the first in the country to implement an overall standard that includes climate change education in every grade and nearly every subject. Across the Delaware, interdisciplinary climate change education is already making an impact.

A climate education leader

Just shy of half of U.S. states include climate change in their middle and high school science curricula, according to The Washington Post. But science alone is not going to cut it, says Dr. Lauren Madden, a professor of elementary science education at The College of New Jersey, who helped develop the new New Jersey standards. “We need people to understand the comprehensive nature, the economics, the communication, the artistic representations and what’s happening.”

Yes, the process of how carbon emissions impact our climate is science. But governments are creating policies to address climate change — that should be part of civics education. There’s a role for climate change in economics: How does it impact supply and demand? And in art, not just when it comes to sustainable materials, but also when it comes to expression. There’s climate change international and social studies to be learned, and math — charting impact, calculating probability. Of course, technology: How can we build more efficient tech, and software that predicts and helps solve problems down the pike?

A study out of San José State University found that students who took a yearlong course about carbon and climate change reduced their own CO2 emissions by 2.86 tons on average — and that widespread climate education could have as much of an effect on curbing climate change as rooftop solar or electric car use. And the importance is backed up by residents: According to a Fairleigh Dickinson University study from May 2023, 70 percent of NJ residents support schools teaching about climate change.

Climate change education also prepares students for the future. As the economy transitions to include more green jobs, more kids will grow up to work in industries that have been reshaped — or invented — because of climate change. “Their future job prospects might very well be manufacturing solar panels,” says Madden. “Wouldn’t it be great to know that kids understood the purpose behind their future work?”

Back in the Garden State

New Jersey began the process of updating its state learning standards to include climate change education in 2019, when NJ First Lady Tammy Murphy — who is on the board of former Vice President Al Gore’s Climate Reality Project — met with more than 130 educators across the state, as part of its every-five-year educational standards review.

The new standards were voted in in 2020. Last year, students started receiving climate education in every subject except math and English. (The state will decide whether or not to include climate education in those subjects later this year, as their standards are on a different cycle.)

Christa Delaney is a high school environmental science teacher at Egg Harbor Township (EHT) High School in New Jersey, whose demographics aren’t dissimilar to public schools in Philly. “There’s a big focus on solutions,” Delaney says. “I find that what they [her students] are asking me now is, Well, what are we going to do about it, and what are some solutions that can be put into place?”

Delaney’s students have presented projects to the Wildwoods’ mayors on how the community can prepare for coastal flooding. They’ve found increasing coastal resiliency, the process of using green infrastructure like grass, plants and sand to reduce erosion and flooding, could help prepare the community for future storms. Some have competed in New Jersey’s student climate challenge, presenting a project on reducing food waste and one one the Trenton-based company TerraCycle, which collects waste previously considered non-recyclable and finds ways to reuse it.

Next year, one EHT student will be working with Delaney on an independent study on climate change and urban planning. “My students now are amazing. They just are go-getters. They’re ready, and they’re coming up with their own solutions and telling me what they want to do,” Delaney says.

Preparing teachers

Including climate education in every subject and every grade level has been challenging, especially for educators in the humanities or social sciences. Making things more difficult: The state of New Jersey doesn’t mandate curriculum. So teachers need to integrate climate change into their own lesson plans.

“It’s up to 590 independent school districts, 2,500 schools, and 150,000 school teachers to implement them,” says Randall Solomon, executive director of Sustainable Jersey, a statewide network of municipalities and school districts that advocates for sustainability. “That is no easy task.” Sustainable Jersey for Schools, an offshoot of Sustainable Jersey, found that professional development and curriculum resources were two of the top challenges teachers faced when trying to introduce climate change education.

To solve this, New Jersey has earmarked $5 million to help teachers attend professional development sessions and make climate change-centered lesson plans. Sustainable Jersey and national pedagogical resource creator SubjectToClimate are holding training sessions for teachers to help them meet the new standards. So far, Sustainable Jersey’s sessions have reached about 600 educators. “We have a long way to go,” Solomon admits.

“My students now are amazing. They just are go-getters. They’re ready, and they’re coming up with their own solutions and telling me what they want to do.” — Christa Delaney, environmental science teacher at Egg Harbor Township High School

That’s why Jersey is also investing in virtual resources. Regional nonprofits worked with SubjectToClimate on the New Jersey Climate Education Hub, a site where teachers can share lesson plans and resources for achieving the new standards’ goals.

Other states are already following New Jersey’s lead. Connecticut added interdisciplinary climate change education to its learning standards for grades 5-12 in 2022. SubjectToClimate co-founder and COO Margaret Wang says that cohorts of teachers in Hawaii, Oregon and Wisconsin are participating in SubjectToClimate’s professional development programs. She’s in talks with several other states (she’s not saying which ones just yet) to create dashboards similar to the one they worked on with New Jersey.

Garner says that if Pennsylvania were to follow suit, the School District of Philadelphia would likely get more funding to expand its curriculum and professional development program. Right now, the efforts have been funded in part using grants from the Franklin Institute; the William Penn Foundation gave a grant to Fairmount Waterworks to support the development of the Understanding the Urban Watershed curriculum.

“We have a great foundation to build from,” Garner says. “If there was anything that was going to be expanded upon from a state mandate, I would hope that they would consider how they could support making this possible with funding and resources.”

![]() MORE WAYS WE’RE IMPROVING EDUCATION IN PHILLY

MORE WAYS WE’RE IMPROVING EDUCATION IN PHILLY