As we contemplate yesterday’s Supreme Court decision that will end affirmative action, and the continued attacks on all things dismissively described as ‘woke,’ it serves us well to consider how affirmative action has played out, and continues to play out, in our lives and for whom. As an entrepreneur, and cofounder of the B Corporation movement, I’m particularly curious how affirmative action has played out and continues to play out in business.

As entrepreneurs, we worked hard. Late nights and early mornings. Weekends. We bootstrapped. We hustled. We earned our money.

This is true. And I have also come to understand that this narrative — the one where we work our butts off to get what we deserve — is more complicated than many of us would like to admit. In reality, this American Dream doesn’t extend equally to everyone. It didn’t in 1993 when I co-founded the popular basketball company AND 1, the subject of a recent documentary on Netflix. It doesn’t today.

Follow the money

Let’s look at the facts. Consider, for example, that more than 60 percent of seed funding for startups comes from friends and family. But what if you don’t know any friends or family with cash to invest? That’s a headwind.

According to the Federal Reserve, in 2019 the median White household was worth $188,200 — 7.8 times the wealth of the typical Black household ($24,100). This means that Black entrepreneurs are much less likely than their White counterparts to be able to raise money from friends and family because, in most cases, their friends and family don’t have money to invest. Having fewer resources to meet even basic household expenses means fewer resources to put toward starting a business or investing in one. The lack of assets also makes it more difficult for Black entrepreneurs to access credit to finance their startups.

Ask yourself this question: Would I rather be a White or Black entrepreneur with no class advantage?

What about venture capital? Black entrepreneurs receive only 1 percent of venture capital investment despite representing roughly 14 percent of the U.S. population. Some investors believe this underinvestment is a “pipeline problem.” Putting aside any individual bias on the part of White investors, the fact that Black entrepreneurs must overcome racial disparities in education, healthcare, housing, criminal justice, government policy, and in the workplace, though, seems to be a far more rational explanation for why there are, or are perceived to be, too few Black entrepreneurs who are investment ready.

This perception — more accurately, misperception — matters. Especially among White investors (White men in particular), since over 98 percent of the $71 trillion in assets under management in the U.S are managed by White men. So unless we believe that Black people are generally less intelligent or more lazy than White people, this “pipeline problem” some investors perceive is more accurately described as a racial advantage problem.

I experienced this dynamic myself at AND 1.

The racial advantage I benefited from began with the head start of the financial capacities and social network of the AND 1 cofounders. Access to $50,000 of startup capital from family and friends was just one element of our racial advantage.

White connections

When we were assembling our board of directors, a CFO client of my dad’s agreed to join, giving us not only the benefit of his decades of industry experience, but also the credibility that came with it. The parents of another cofounder were intellectual property attorneys, so we received valuable and pricey legal advice for free and were able to make filings to protect our intellectual property at cost. They also introduced us to partners at a prominent accounting firm with a large apparel industry practice, so again we benefited from very high quality, very low-cost expertise in setting up and financing the growth of our business.

The partners of the accounting firm introduced us to a factor (a specialty kind of financing firm) who would purchase our receivables and advance us 85 percent of the value so we could pay our suppliers and off-load the risk and administrative burden of chasing down payments. AND 1 was also extended credit (typically 30 days from invoice) from the screenprinters and factories that made our products. This meant that if we could sell it, we could finance it; no working capital constraints. These financing partnerships were unusual for a startup, and a huge advantage. Most of these connections and trust are not available to Black entrepreneurs.

Over 98 percent of the $71 trillion in assets under management in the U.S are managed by White men.

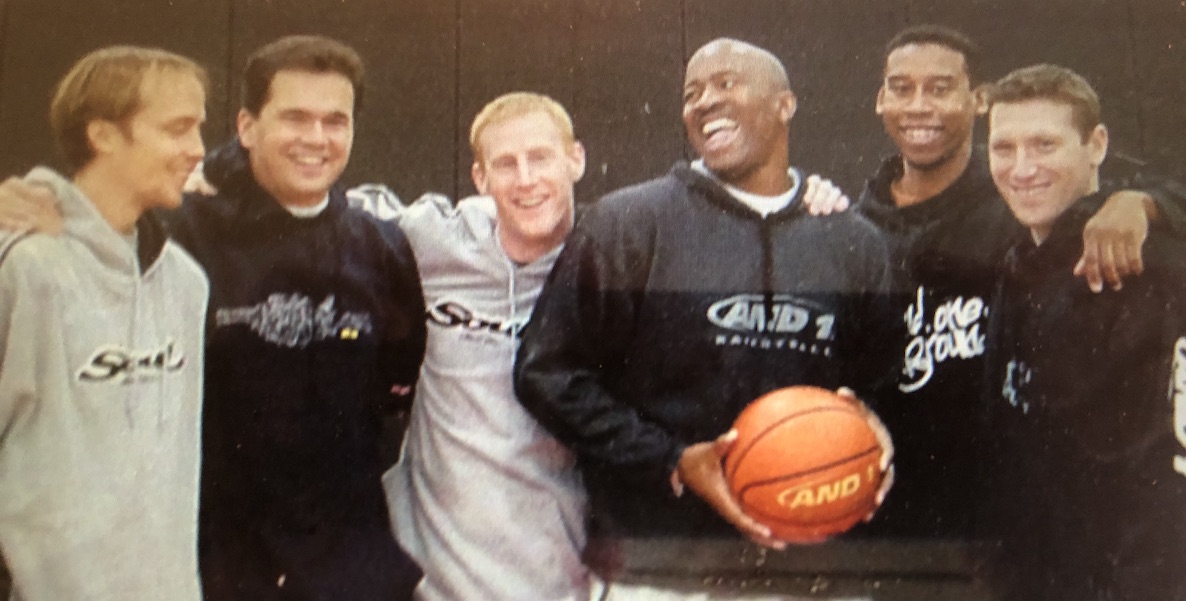

Here’s a telling thought experiment: AND 1 had six partners — the three cofounders (all White) and three friends who joined us within our first year (two who are Black). AND 1’s Black partners were both from solidly middle class families, both graduated from elite colleges (Howard University and Pepperdine), one had the same Wharton MBA as one of the cofounders, and both had early resumes as strong as the cofounders, with one arguably having the strongest resume of all the partners, having worked at IBM and Smith Barney. If our roles were reversed and our two Black partners were AND 1’s co-founders trying to raise that initial startup capital, could their family and friends have come up with $50,000? Could they have worked for a year without pay? If we had tried to help them raise money, would our friends and family have given them the same level of trust and support as majority-controlling owners that they gave to us?

Another example of advantage relates to the ability to take risks. Risk looks and feels different for White founders and Black founders, and this dynamic plays a significant role in the inequity of startup experiences between them. This was the case for me and my co-founders at AND 1.

As I recall, one of our competitors, in the market before us, worked at a Boys & Girls Club in Chicago and was pursuing his dream of starting a basketball brand in his spare time. He was solo. He was Black. AND 1, on the other hand, already had a three-person founding team working full time — two without pay, one for a salary of $25,000. We could take this risk because together we had enough personal money in the bank, credit cards, and the luxury of strong family safety nets and brand-name educations to fall back on. Ignoring for a moment many other important variables, assuming our Boys & Girls Club competitor was working on his basketball business half time, which is a big assumption, that’s a 6x advantage for us just in manpower alone right out of the gate. We were set up for success against this competitor without selling one piece of merchandise because of the risks we were willing and able to take.

Just like us

Not every White entrepreneur has these advantages, which seem as much about class as race. True. However, given the hundreds of years of racial advantage and disadvantages in the U.S, and how those advantages and disadvantages have compounded over time, resulting in the racial wealth gap and other racial disparities, race and class are intricately related. Also, given the statistics shared above and your own lived experience, ask yourself this question: Would I rather be a White or Black entrepreneur with no class advantage?

This racial advantage plays out from startup to sale, often in ways we don’t see if we’re not looking.

Most senior managers at AND 1 were White largely for the same reason that our friends and family investors were White: our social networks were largely White. Many of those hired, most often without any robust interview process, were “just like us,” people we knew and liked and trusted: friends from college; a sibling of a friend from college; a co-worker from a first banking job; a next door neighbor; a friend of a friend; a former student of a friend, and then his friend; poached talent from our ad agency; ballplayers and their friends from a nearby college where we balled at lunch and knew the coach. Almost all White. Predominantly men. This means that the people who benefited financially from the success of AND 1 were predominantly White men. A self-reinforcing cycle of racial (and gender) advantage perpetuated by people who were not racist.

Racism — in the form of systemic racial advantage or disadvantage — can exist without racists.

The success of AND 1 was the result of a great idea well executed with a lot of hard work at the right time in both our culture and the industry. The success of AND 1 was also the result of the advantage of its White (and male) cofounders (from relatively well-off families). For me, AND 1 created wealth I can pass down to my kids, and maybe to my grandkids, passing down advantage that I hope they will deploy in part for the benefit of others.

A racist setup

But the success of AND 1 also reveals an uncomfortable truth, one that I believe not nearly enough business leaders are willing to acknowledge. The most important thing my experience, and the experience of so many entrepreneurs like me, has revealed is that racism — in the form of systemic racial advantage or disadvantage — can exist without racists. (Yes, there are an alarming number of those today, but not many public ones in the worlds of investment and entrepreneurship.) The legacy of hundreds of years of racial inequity is in our groundwater, invisibly seeping into every system and structure in our companies, communities, and country.

Which brings me back to why I wrote this essay. Today, a majority of White Americans (52 percent) believe that White people do not benefit from any societal advantages compared to Black Americans (Pew, 2021; NPR/Ispos 2020). Until this number drops significantly, I believe we will not make material progress toward achieving a fairer sort of entrepreneurship: one that rewards talent and vision first and foremost, not connections, inherited wealth, and race.

The playing field in America is not and has never been level. Yes, we have made important strides. But no number of DEI departments or diversity initiatives can make up for generations of injustice and inequality.

My hope is that when we normalize the experience of seeing, hearing, and reading other White men talking about their success as a product of their smarts and hard work, and also as a product of their advantage—their head start, their tailwind, and their relative lack of obstacles—we’ll all be in a better place. One where all have the opportunity to become their best selves, work for the best companies, and build the strongest communities, all working together to make this place the greatest country we can be.

Jay Coen Gilbert is the co-founder and former CEO of B Lab and founder of IMPERATIVE 21.

The Citizen welcomes guest commentary from community members who represent that it is their own work and their own opinion based on true facts that they know firsthand.

![]() RELATED COVERAGE OF BLACK-OWNED BUSINESSES IN PHILLY

RELATED COVERAGE OF BLACK-OWNED BUSINESSES IN PHILLY

AND 1 partners in 2001. Left to right: Tom Austin*, Bart Houlahan, Jay Coen Gilbert*, Ray Moseley, Guy Harkless, and Seth Berger*. * Cofounders