This article is the first installment in a four-part series looking at the state of play in Philadelphia’s built-environment politics following the 2023 primary election. In this series, we’ll outline some potential areas of alignment between the pro-growth constituencies who supported presumptive Mayor Cherelle Parker’s campaign, and voters in the neighborhoods that turned out most strongly for Parker.

The first installment provides some background on the idea of the “growth machine” coalition and its relevance to Philly politics in 2024. Future newsletters in this series will dig into some of the specific policy areas of interest, like transportation and infrastructure, housing, fiscal policy, and some other odds and ends.

What’s a growth machine coalition?

One of the more hopeful potential outcomes of Philadelphia’s 2023 primary election is that the classic big city “growth machine” coalition of labor unions, builders, and some segments of the business community might finally have a little more political juice in City Hall than they’ve had in a while as a result of the political coalitions that came together to support Democratic Mayoral nominee Cherelle Parker and some of the new and returning members of City Council.

The term “growth machine” comes from an influential 1976 paper “The City as a Growth Machine: Toward a Political Economy of Place” by the sociologist Harvey Molotch. Molotch’s argument was that much of what drives municipal politics has to do with a powerful alignment between the city government and its constant need for more jobs and tax revenue, and the various elite interests who try to direct economic development toward their own land or their own jurisdiction instead of somebody else’s.

Municipal governments exist to perform lots of essential local service functions, but what inspires some of the most intense lobbying and politicking at the municipal level is the local government’s role in creating the preconditions for growth, distributing the public investments that will lead to growth, and competing against other municipalities for growth. Local government has become part of a “growth machine” when it becomes preoccupied with catering to this set of concerns.

What’s Philadelphia’s growth machine?

Molotch was writing as a critic of this dynamic, but the paper has a lot of good insights too for people who are more favorable to the growth machine lens on politics. The most salient point for the present day is about how a lot of disparate interests who may disagree with one another about other areas of local politics can often agree on the economic growth imperative, and this baseline agreement is a powerful force that disciplines municipal officials and shapes the contours of what they believe about the scope of political possibility.

The growth machine term has expanded in its popular usage to also describe the loose coalition of organizations who participate in politics with these goals in mind — builders, unions, chambers of commerce, large individual businesses, sports franchises, tourism-related industries, and so on. The list of organizations that participated in the BUILD Philly forum is a good starting point for thinking about who this includes.

A lot of disparate interests who may disagree with one another about other areas of local politics can often agree on the economic growth imperative.

For the purposes of this writing, I’ll refer to these groups as the “growth machine coalition” as a shorthand. Some of these groups work closely together on advocacy and lobbying already, and some do not. Some might not see themselves as being aligned with one another at all. The point is to describe a general set of interests that are invested in more economic growth and stand to gain something from it.

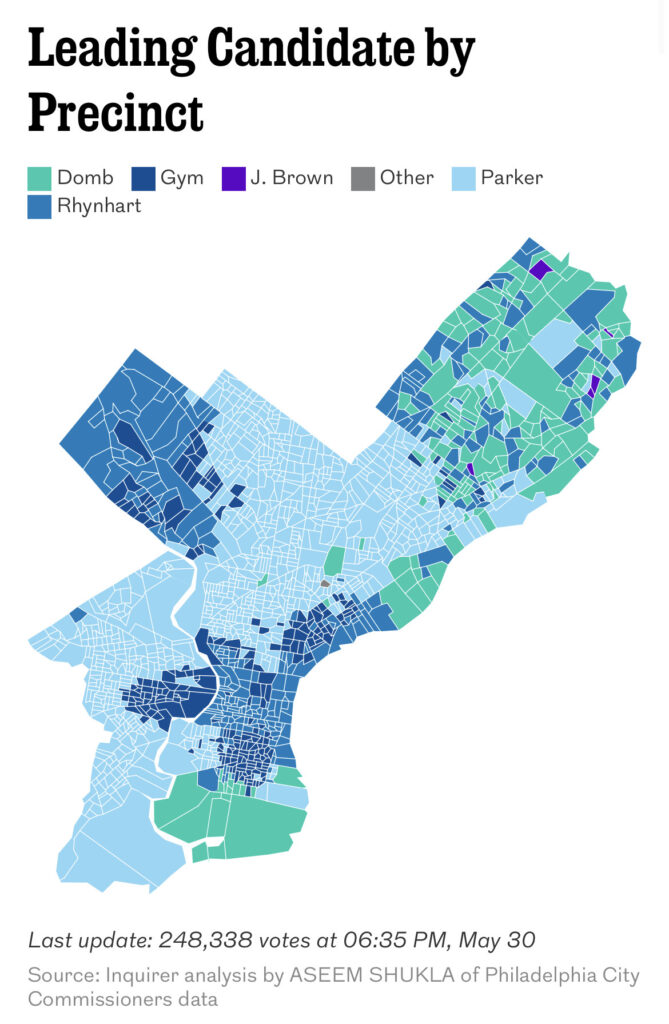

Many of the organizations who participate in Philadelphia growth machine politics supported Cherelle Parker for mayor, who went on to win the Democratic nomination. Some others had supported Rebecca Rhynhart or Allan Domb. It wasn’t necessarily preordained that most of the policy-interested actors in this space would support Parker based on her City Council record or campaign position-taking, though there were some good political reasons for that to be the case.

Is Parker onboard with growth?

As a Councilmember, Parker had somewhat of a mixed record when it comes to development issues that might not have made her the most obvious favorite for growth machine interests, at least on paper. Parker has had some bona fide moments of political courage in standing up for affordable housing in the 9th District, mixed with a few disappointing moments crusading against priority issues for Philly’s affordable housing advocacy community.

She also sent some mixed signals about how she’d govern on this topic during the mayoral campaign, alternating between some pro-growth messages: “As the poorest big city in the nation, Philadelphia doesn’t have the luxury of engaging in reflexive opposition to any project that has the potential to offer a game-changing economic impact, especially for Black and Brown workers and businesses,” she said, and more neighborhood-protectionist messages: “I won’t allow anyone to engage in I know what’s best for youse people policymaking.” Given all that, it’s a little hard to guess exactly where a Mayor Parker might come down on the various issues related to growth and development in the city.

There is, however, some broad recognition that the Philadelphia Building Trades, under the leadership of Ryan Boyer, played a pivotal role in electing Parker as the Democratic nominee for mayor. Parker also received notable support from corners of the business world and development interests.

Speaking at an event in early June, Boyer laid out an appealing vision of a Philadelphia that dreams big, builds big, and lifts everyone up in the process.

“At the event, hosted by NABTU at the Laborers’ District Council Training Center in North Philadelphia, labor leaders and politicians spoke of a future in which a growing population of union tradespeople — one that’s more diverse than ever before — rides federal infrastructure investments and state-funded projects to a middle-class living, or better […]

“If you’re Black, if you’re White, if you’re male, if you’re female, if you’re nonbinary — if you wanna work hard and you want to put up with the rigor, you have a place in the Philadelphia Building Trades,” Boyer said.

The next mayor’s influence

The next mayor will have considerable influence over the direction of the city’s federally-funded infrastructure projects when applying for funds from the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (IIJA) and Inflation Reduction Act (IRA.) Some of this work is already underway regarding the transportation and energy-related investments the Kenney administration is pursuing, but there is a lot of room for the next Mayor to put their stamp on this too.

Perhaps more importantly, the next mayor and City Council will influence the overall amount and direction of economic growth in the city through their choices of agency and board appointees, and what kinds of legislation they decide to pursue.

One interesting question for the Mayor Parker era is going to be what kinds of infrastructure projects or policy priorities could unite both the voters in the places that won the primary for Parker, and the growth machine coalition that supported her campaign.

The Northwest neighborhoods and their elected representatives have not shown much appetite for having more growth and development right in their backyards in recent years, as rising land values have brought more new construction activity to places like Mt. Airy, Germantown, Roxborough, and Manayunk. But voters also want to benefit from the proceeds of growth from more jobs and tax revenue and improved City services.

One possible synthesis of these somewhat conflicting political currents could involve prioritizing pro-growth outcomes in some of the high-value downtown-adjacent areas that didn’t vote for Cherelle Parker for Mayor, while directing more of the resulting benefits from tax revenue and infrastructure spending toward the places that did.

Jon Geeting is the director of engagement at Philadelphia 3.0, a political action committee that supports efforts to reform and modernize City Hall. This is part of a series of articles running on both The Citizen and 3.0’s blog.

![]() MORE ON ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT FROM THE CITIZEN

MORE ON ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT FROM THE CITIZEN